![]()

Part 1 · The “Emperor” Strikes Back

Les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux pillard.

“The white man’s letters on the hordes of the old plunderer.”

Les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux billard.

“The white man’s letters on the cushions of the old billiard table.”

—RAYMOND ROUSSEL, “IMPRESSIONS OF AFRICA”

![]()

1 · Invitation to a Beheading

The colonizer constructs himself as he constructs the colony.

The relationship is intimate, an open secret

that cannot be part of official knowledge.

—GAYATRI SPIVAK, A CRITIQUE OF POSTCOLONIAL REASON

In the mid-1970s, people living in the large village of Lubanda in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), readily recalled the name and a few of the exploits of Bwana Boma, despite his having lived there for a mere two years nearly a century before. Bwana Boma is the local sobriquet for Émile Pierre Joseph Storms (1846–1918), Belgian leader of the fourth caravan of the International African Association from Zanzibar to Lake Tanganyika that arrived deep in the heart of Africa in late September 1882 (fig. 1.1). The name Bwana Boma means “Mister Fortress,” and it was chosen during Storms’s days at Lubanda because of the formidable stronghold Storms constructed there in 1883.1 Storms was an assertive young man who sought to leave his mark on European conquest of the Congo. With acuity and irony, a Belgian journalist noticed Storms’s unmitigated ambition and heralded him as “Émile the First, Emperor of Tanganyika.”2

Of Bwana Boma’s many adventures, the one that proved pivotal to his proto-colonial project was a punitive expedition he mounted (but did not himself lead) in early December 1884. The goal was to sack the mountain fastness of Lusinga, a most “sanguinary potentate,” in the estimation of Joseph Thomson, the Scottish explorer who visited the chief in 1879.3 Lusinga commanded men engaged in ruthless pillaging and slave raiding in a wide area north of Lubanda, and such activities seemed justification enough for Storms’s attack. Yet as we shall see, he had more deep-seated reasons as well.

Setting the Scene

The mid to late 1800s were turbulent years in what is now known as southeasternmost DRC. Beginning around 1830, Swahili adventurers from coastal east Africa circumambulated or crossed Lake Tanganyika to hunt elephants and take slaves in the Marungu Massif and adjacent lands. The term “Swahili” and the related designation wangwana referred to “free-born” coastal men, as such social references were understood as far inland as Lake Tanganyika. These were expansive as well as prestigious identities, and non-coastal people could “reinvent themselves as waungwana by appropriating coastal culture, [and] by dressing and living a waungwana lifestyle” that included rich displays of consumer items and related material culture.4 Storms noted that persons who presented themselves as “free-born” might remain enslaved in Zanzibar but possess significant autonomy in the interior. As one scholar has reflected, “The slave who had simply spent time in Zanzibar, even for a short while, was called an Ngwana ‘free man’ thereafter; . . . every askari, by the sole act of having taken part in a military escort, became an Ngwana; . . . [and] far from Zanzibar, the Arab, the free Swahili person, the slave of the coast, all were labeled wangwana.” Such a fluid sense of what constituted “free-born” challenges what being “enslaved” must have meant in the same circumstances, as understood across different languages and social practices as well as through individual cases. Indeed, Stephen Rockel argues that wangwana “were at the cutting edge of African engagement with international capitalism, that they were the prime movers in the economic, social and cultural network building of the period, and that they expressed an alternative East African modernity.”5

Swahili and wangwana were soon seconded by or competing with mercenary brigands known as rugaruga, who hailed from what is now north-central Tanzania. In the words of historian Aylward Shorter, rugaruga were “wild young men, a heterogeneous collection of war captives, deserters from caravans, runaway slaves and others. They were without roots or family ties, and they owed no allegiance other than to their chief or leader.”6 Rugaruga often acted as highwaymen, harrying straggling caravans. As Storms noted, “When a caravan crosses the land, it is considered a great godsend [aubaine], a favorable wind that has brought resources and circumstances that chiefs exploit as much as possible.” No wonder that a few years later, a European stalwart found rugaruga to be “real vultures” preying upon the weak and robbing the dead.7 Storms’s phrase “a favorable wind” may have been a common expression in French, but it resonated with how local people would have understood such “good fortune”: a pepo, or spirit—literally a “wind”—would be the agent leading the caravan into rugaruga clutches. Tabwa would comprehend the European metaphor of rugaruga as “vultures” in their own way as well, for like these remarkable birds, the brigands benefited from an extraordinary ability to locate caravan “carrion” over great distances. Indeed, vultures are deemed to possess a supernaturally extended ken that Tabwa call malosi as an attribute shared with hyenas and a few other predators and scavengers.

Ivory and slaves that rugaruga obtained to the west of Lake Tanganyika by commerce, force, and wile were sold to Swahili or Omani (collectively called “Arab”) traders based at Ujiji as of the 1840s, and at several less significant entrepôts along the eastern shores and to the south of Lake Tanganyika. Some of the enslaved were settled around Ujiji and adjacent areas, but most were taken to the trading town of Tabora in what is now north-central Tanzania as a place that served as “the veritable knot of communications to which caravans converged and from which they left in all directions,” to paraphrase Jérôme Becker.8 Émile Storms commented on how in mid century, “Arabs” at Tabora and elsewhere were almost exclusively engaged in plantation agriculture, for which enslaved people provided the labor, but that after 1873 when slavery was abolished in Zanzibar, labor availability changed and the same Arabs became agents for Indian merchants in Zanzibar who were largely responsible for the burgeoning international trade in ivory. Those not put to work around Tabora itself were forced on to coastal cities or offshore islands for dispersal into the Indian Ocean world and beyond. Storms also noted that an enslaved person purchased for five piasters along the southwestern shores of Lake Tanganyika would be worth fifty to one hundred or more in Zanzibar, thereby suggesting relative market values despite how prices fluctuated from place to place and moment to moment. And for every enslaved central African who survived to reach coastal ports, a great many died in raids upon their communities or in harrowing transit from the interior.9

In the 1870s Lubanda was “a place of much importance as the principal starting-point of the caravan route adopted by Arab traders from Ujiji to Lake Mweru and Katanga.”10 Saïd Barghash, the Omani sultan of Zanzibar, may have stationed a representative at Lubanda for some years to take advantage of “one of the richest mines of slaves” that the hinterland presented at the time. According to one account, the famed trader Sheikh Saïd bin Habib lived at Lubanda in the 1870s, and then a few years later, the even more renowned Juma Merikani, whom Verney Lovett Cameron met south of Lubanda and who would befriend several European explorers, was there as well, but whether they were resident at Saïd Barghash’s behest is not clear.11

The prominence of Lubanda was undoubtedly why David Livingstone was brought there in mid-February 1869, following his visit to King Kazembe and exploration of what is now northeastern Zambia. He remained in Lubanda for about two weeks, too close to death from pneumonia to leave diary entries describing his stay.12 Livingstone did write that Saïd bin Habib was in “Parra”—that is, Lubanda as the village of Chief Mpala (“Parra”)—and maintained two or three large pirogues there. When the explorer was finally strong enough, he was conveyed northward by these vessels, arriving at Ujiji, where he could recover his health with the help of resident coastal traders. Livingstone would remain in the area, taking a long trip northwest of Lake Tanganyika before returning to Ujiji to be “discovered” so presumptuously by Henry Morton Stanley in late 1871.13 A century later, people in Lubanda showed me where they believed the boat taken by Livingstone had been moored.

Lubanda was only of fleeting importance as a point from which to cross Lake Tanganyika, for rugaruga soon blocked the route inland as they sought to dominate ivory and slave trading. Thereafter, Lubanda resumed its status as an especially large and prosperous cluster of lakeside hamlets known not only for unusual agricultural productivity and lake and river fishing but also as a place vulnerable to pillaging because of just such abundance.14

In late 1879 an affable young Scotsman named Joseph Thomson—a tender twenty-one at the time—hiked along the rugged southwestern shores of Lake Tanganyika, visiting small villages wherever a cove or scrap of flat land permitted settlement in otherwise steeply mountainous terrain. Thomson headed the Royal Geographical Society’s East African Expedition of 1878–1880 after the death of the original leader, Keith Johnston. As opposed to the era’s shoot-first-ask-questions-later ethic of European explorers riding about in their tipoy portable hammocks and accompanied by lavish caravans, Thomson personally led his modest party unarmed and on foot. And although he was sometimes confronted by defensive parties who feared he might be leading a slave raid or other attack, in each instance Thomson was able to prove his peaceful purposes without further incident, “his youth and high spirits” getting him through all such scrapes.15

In 1881 an anonymous reporter for the New York Times found that “it was indeed a singular fact that a mere boy . . . should make so rapid a march as he, so long a journey, and one through so many different tribes of all degrees of semi-civilization, without the loss of a single porter, and, what is infinitely more to his credit, without the sacrifice of a single life among the tribes he passed.”16 One must be cautious with regard to any so heroic a portrait, however, for as Johannes Fabian suggests and we shall discuss in chapter 4, Thomson’s “youthful impetuousness and Scots radicalism” call for skepticism concerning some of his pronouncements.17 Despite the Times reporter’s hyperbole, the young man did stand out as an exceptional Victorian visitor, however. As Robert Rotberg has suggested, “Thomson, virtually alone of the leading explorers of Africa, professed to have liked Africans and to have attempted to treat them as equals—and not in accord with some abstract principle, but in an unaffected, natural way.”18

Moving northward toward Lubanda, Thomson was impressed with the lot of local people: “Seldom or never making war, they live in the utmost comfort, in possession of an extremely fertile region, which yields food in great variety and abundance.” He also admired the “cleared and cultivated fields of indescribable richness, producing wonderful crops of Indian corn, millet, ground-nuts, sweet potatoes, voandzia [‘Congo goobers’], beans, and numerous other kinds of vegetable food.” Indeed, he surmised that local people “have not a want which they themselves cannot supply.”19

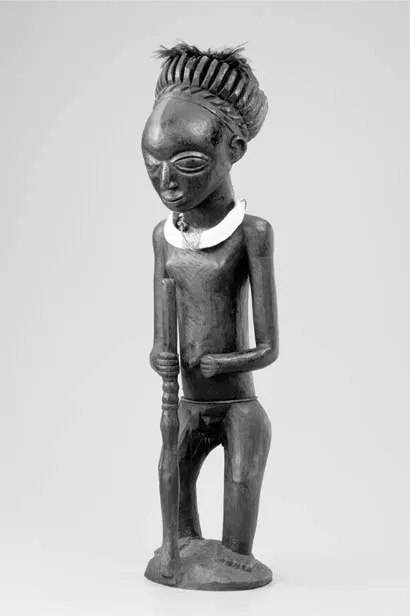

Thomson was well received at Lubanda by Sultani Mpala, who insisted that he and his retinue enjoy the chief’s hospitality and spend the night. Continuing north along the shore, Thomson traversed another “charming piece of country” to arrive at Cape Tembwe, a promontory extending a good ways eastward into Lake Tanganyika. The scene then changed radically, from Thomson’s Edenic pastoral to one of bleak devastation, for the large village at Tembwe was “packed with refugees” from surrounding areas laid waste by slave raiding. Despite such turmoil, local chief Fungo and the Scotsman “soon became the best of friends,” suggesting reasonable behavior on both sides. Until two or three years before Thomson’s visit, Fungo “had had a considerable number of villages under him,” but now only Tembwe remained, the others having been destroyed by a chief “known as Kambèlèmbèlè, or ‘Swift-of-Foot,’ though his proper name is Lusinga” (fig. 1.2).20

Figure 1.2. Ancestral figure of Lusinga and his matrilineage. H. 70 cm.; wood, bushpig tusks, feathers, reptile skin, fiber cord; unknown artist. EO.0.0.31660, collection RMCA Tervuren; photo R. Asselberghs, RMCA Tervuren © with permission.

In the 1860s and 1870s, Lusinga and a few other local chiefs began consolidating and legitimizing their authority through emulation of eastern Luba models of dynastic political economy while gaining ever greater power by taking advantage of turmoil caused by intrusive slave raiders.21 Some of these latter visited the southwestern shores of Lake Tanganyika, but population density was generally too thin and the terrain too rugged to encourage any of them to stay for long. While the economic stakes did not attract settlement by those with the means to seek greater profits elsewhere in the region, Swift-of-Foot did establish himself but followed the slave traders’ ruthless modes for increasing his wealth and power at the expense of local people. Furthermore, by locating his base of operations in a remote location between slave routes and entrepôts, Lusinga was able to participate in the trans-regional political economy while remaining sufficiently “local” to enjoy the advantages of lineage and clan affiliations.

Great power could be had quickly by marshaling even a small force of heavily armed rugaruga as Lusinga did to engage in small-scale trade in ivory and slaves. Storms would write that “every native chief possesses rugaruga. . . . If he makes war all men take up arms, but the rugaruga constitute the principal core. In peaceful times, the rugaruga have as their profession brigandage for the chief.” The lieutenant further noted that “war is imposed upon chiefs, for if they do not wage it, they will lose their rugaruga who will go and place themselves at the disposition of a neighboring chief...