![]()

Part One: | Markedness, Topics, and Tropes |

![]()

1 Semiotic Grounding in Markedness and Style: Interpreting a Style Type in the Opening of Beethoven’s Ghost Trio, Op. 70, no. 1

Beethoven’s Piano Trio in D Major (Ghost), Op. 70, no. 1, was composed in 1809. Its minor-mode slow movement, Largo assai ed espressivo, is filled with such chromaticism and tremolos that Czerny (1970: 97) associated it with the scene from Shakespeare where Hamlet encounters the ghost of his father. William Kinderman (1995: 134) notes that the uncanny attribution is literally warranted; however, the connection is not with Hamlet but with Macbeth. In 1808 Beethoven was sketching ideas for an opera based on a Macbeth libretto by Heinrich von Collin, and sketches for the abandoned opera project are found interspersed with ideas for the slow movement of the trio.

If a semiotic approach to musical meaning depended on such programmatic suggestions, I might well have chosen the slow movement for investigation. But it is to the decidedly less gloomy first movement that I wish to direct attention, specifically to the opening theme complex. I plan to demonstrate how we can come to a deeper understanding of the expressive meaning of this opening by pursuing evidence from a variety of perspectives. My semiotic approach is both structuralist, in reconstructing the stylistic types that correlate with general expressive meanings, and hermeneutic, in interpreting the strategic designs through which a composer individualizes and particularizes the tokens of those types, thereby achieving unique expressive meanings. And my approach is directed toward understanding how music has meaning, not merely what it might mean, from the perspective of a historically informed reconstruction of the style. In the course of teasing out the subtleties of the opening of the trio, I will demonstrate the breadth of my semiotic approach, not as a substitute for other kinds of analysis, but as a means of interpreting their results and revealing further aspects of the work’s expressive design.

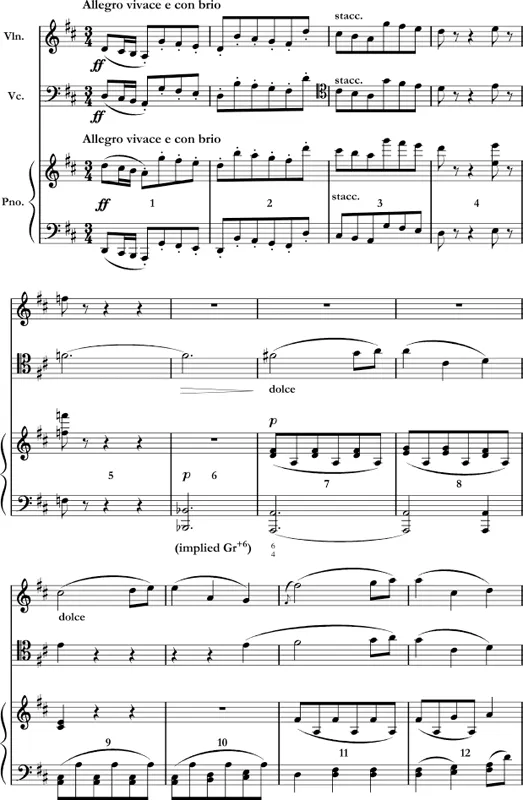

A characterization of the first theme complex (

Example 1.1), from the opening up to the counterstatement launching the transition at m. 21, might read like this: “With an energetic burst akin to the opening of the Piano Sonata, Op. 10, no. 3, the unison opening motive, x, sequences upward before breaking off with a surprise shift to F

♮. Sustained in the cello like a written-out fermata, this F

♮ is then supported by a consonant B

♭ in the piano, before moving to an F

♯ above a cadential

and the elided beginning in the cello of a more lyrical first theme, y.” This description blends structural terminology (motive, sequence, cadential

, elision) with expressive characterizations (“energetic,” “surprise shift”), and even draws intertextually on a similar piano sonata opening. A closer analysis, perhaps inspired by Schenkerian voice-leading and an intuition about elliptical structures, might claim that the B

♭–F consonant fifth in m. 6 implies an unstable German augmented sixth, which resolves in contrary motion by half steps to a cadential

, and thus the whole opening may be understood as a briefly interrupted expansion of a key-defining progression.

1 Students of Leonard B. Meyer (1973) might emphasize the delayed realization of an implied F

♯ (deferred by F

♮), or point out that the thematic arrival in m. 7 is not

congruent with the proper arrival of the tonic in the bass, which is delayed until m. 11. And disciples of Rudoph Réti (1951) would delight in discovering that the cello idea, “y,” is an augmented inversion of the opening “x” motive, suggesting the presence of a unifying

Grundgestalt, Schoenberg’s term for a generative thematic contour or cell.

Example 1.1. Beethoven, Piano Trio in D Major (Ghost), Op. 70, no. 1, first movement, opening themes.

More historically oriented interpreters would cite E. T. A. Hoffmann’s instructive review of 1813 (in Charlton 1989: 300–24), observing that what I have labeled as motives x and y are, interestingly, identified as first and second themes by Hoffmann, although he apparently is unaware of their inversional relationship. Based on his review of the Op. 70 piano trios and his better-known review of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Hoffmann is recognized as being the first music critic to demonstrate the organic, motivic, and generational process through which Beethoven develops his larger heroic-period forms. Hoffmann concentrates on the “ingenious, contrapuntal texture” of the development, which he presents in full score, not otherwise available for study in this form at the time of his article. He describes crucial modulations and provides a figured bass reduction of the rewritten transition in the recapitulation, foreshadowing the advent of Schenkerian reductions. Hoffmann is also credited as one of the earliest critics (but see Momigny) to combine structural and expressive insights in his analyses. In this review he comments on the character of the “second theme” (beginning with my motive “y”), noting that it “expresses a genial serenity, a cheerful, confident awareness of its own strength and substance.” I think we might be in general agreement with his assessment, although he offers us no particular reasoning to support it.

After this series of observations, both obvious and subtle, what more is there left to say? We have historical warrant for both theoretical analysis and expressive interpretation of the passage. We have revealed its secrets with respect to the implied German augmented sixth in m. 6, the noncongruence of thematic and tonal arrivals in mm. 7 and 11, respectively, and even the organic derivation of “y” from “x.” Indeed, what more could a semiotic approach offer, assuming we have applied such a range of productive analytical and historical approaches?

A great deal more! For what I have presented thus far is merely analogous to parsing a poem, analyzing its syntax, and offering a subjective impression of one of its moods. We need not blithely accept Schenker’s insistence that pitch structure, with a little metric interpretation thrown in, reveals the “true content” of music (as Schenker implies in the title to one of his Meisterwerk [1930] essays: “Beethovens 3. Sinfonie zum erstenmal in ihren wahren Inhalt dargestellt” [my italics]). Nor should we stop at what sensitive ears such as Hoffmann’s may have heard. Instead, we can further explore how the structures we have discovered might be based on typical meanings in the style, and how they might be creating unique kinds of meanings within the constraints of that style. I call the first kind of meaning a stylistic correlation, based upon the generalization of types; the second kind of meaning is a strategic interpretation, and it is based upon the creation of tokens. A helpful way to explore the meanings of stylistic types is to investigate the structural oppositions that enable us to identify them, and that keep them systematically coherent. Oppositions in a style are asymmetrically structured as marked versus unmarked (see the Introduction), and their markedness values map onto similarly marked-unmarked oppositions in musical meaning. An example will illustrate.

I earlier analyzed the implied augmented-sixth chord in mm. 6–7 as resolving to a cadential

. But this

chord does not sound cadential; rather, it evokes a very strong sense of arrival, hence, my coining of the term “arrival

” (Hatten 1994: 15, 97). Other examples may be found in the slow movement of the

Hammerklavier (m. 14), as well as the coda to the first movement of Op. 101 (m. 90). Notice that the rhetorical effect of resolution of dissonance, as a kind of “breakthrough” arrival, is more telling at the moment the

occurs than at the actual cadence. Here the

is not only an arrival but an

initiation—it launches an important theme and thus functions, however poetically, as a structural downbeat for the “y” theme (while deferring a more powerful, root tonic structural downbeat for the cadence in m. 21 that launches the transition). The lyrical “y” theme unfolds above what at first suggests an ongoing dominant pedal, but harmonically the theme does not sound unstable—unlike the agitated dominant pedal points enhancing the (tragic) obsessiveness of the second themes in the first movements of Op. 2, no. 1 (in the relative major, A

♭, but with mixtural

♭6

̂) and Op. 31, no. 2 (in A minor, the dominant of D minor). The stability of the “y” theme is evidence of a semiotic (and contextual) reinterpretation of dissonance; although the

eventually resolves, it does not do so with a traditional 5

̂–1

̂ cadential bass, but rather slips up by step to tonic (mm. 10–11). Thus, the

is no longer as dependent on its resolution to a dominant, but stands on its own, as a poetically enhanced tonic. There are several motivations for this consonant effect. The theme sounds presentational, as though elevated, and on a pedestal. The dominant pedal provides this pedestal effect, and thus it can be heard as a separate “strand” independent of the stable tonic with which we assume a theme would begin. But the pedal 5

̂ also resolves the instability and rhetorical questioning of the implied German augmented sixth. Just as poignant lowered 6

̂ resolves to 5

̂ in the bass, the questioning lowered 3

̂ is pulled up to raised 3

̂ in the upper voice. The positive, Picardy-third effect of this resolution also enhances the relative stability of the subsequent measures, and the glowing consonance of the major triad offers perceptual affordance to this interpretation. Finally, when we hear the augmented inversion in “y” as a (noble, expansive) transformation of the (hectic) opening motive “x,” its glowing harmonic presentation (as an arrival

supporting a tonic over pedestal dominant) sounds truly fitting.

These are but a few of the contextual reasons for semiotically rei...