eBook - ePub

African Fashion, Global Style

Histories, Innovations, and Ideas You Can Wear

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

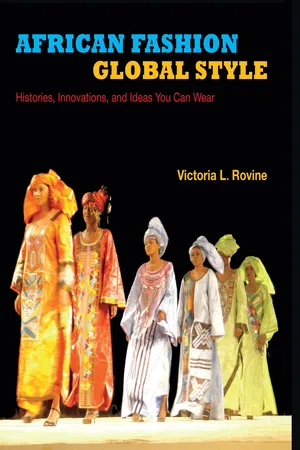

African Fashion, Global Style provides a lively look at fashion, international networks of style, material culture, and the world of African aesthetic expression. Victoria L. Rovine introduces fashion designers whose work reflects African histories and cultures both conceptually and stylistically, and demonstrates that dress styles associated with indigenous cultures may have all the hallmarks of high fashion. Taking readers into the complexities of influence and inspiration manifested through fashion, this book highlights the visually appealing, widely accessible, and highly adaptable styles of African dress that flourish on the global fashion market.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access African Fashion, Global Style by Victoria L. Rovine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Arte africano. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

You come from afar, you have brought lots of clothes, everyone sings your praises, the best clothes come from Accra, and the person who wears them is the best.

—Dogon song, documented by Isaie Dougnon

A tilbi is more than a boubou.

—Baba Djitteye, embroiderer, Timbuktu, 23 July 2008

Indigenous Fashion | 1 |

EMBROIDERY AND INNOVATION IN MALI |

In a single region in Mali, two styles of men’s dress embody diverse forms of social status, attitudes toward innovation and perpetuation of past practices, and sources of stylistic inspiration. These styles, known as “Ghana boy” and “tilbi,” have in common a reliance on embroidery as a means of embodying messages, histories, and identities. Yet, these embroidered garments represent quite distinct approaches to style change, the hallmark of fashion. Neither of these sartorial innovations participates in the global fashion system, which is rooted in Western styles and methods. Instead, they offer insights into different fashion worlds, with their own histories, economies, and precedents from which they draw inspiration. Furthermore, these styles contain traces of local as well as global networks of commodities and cultures, literally made legible in the embroidered patterns and figures that adorn the garments.

The first of these two embroidery forms, known as “Ghana boy” style, differs dramatically from local precedents. Garments in this style illuminate the lives and aspirations of young men in the region who seek status through affiliation with the new and the non-local rather than with past practices. These associations are evident in the iconography of the garments, which often incorporate embroidered depictions of figures in miniskirts, bellbottoms, and police uniforms, along with airplanes and motorcycles. The second type of embroidery, used to create a garment style called “tilbi,” offers a counterpoint to the Ghana boy style and expands the field of African fashion to include a self-consciously conservative dress form. The tilbi is a style of boubou, a general term used in Francophone West Africa to describe large, wide-sleeved, untailored robes worn in different styles by men and women. Tilbi boubous illuminate the deep roots of embroidery in the region, because this style perpetuates a longstanding dress practice even as it responds creatively to new influences. While tilbi are made in women’s styles, my focus here is on the role of the garment in men’s dress practices. These long, flowing robes are adorned with abstract motifs that are embroidered using intricate and labor-intensive stitches. Their association with local history, scholarship, and religious belief enhances the meaning and value of these garments.

A comparison of these two styles of embroidered garments elucidates the motivations and sources of inspiration that have influenced their makers. My analysis of the Ghana boy style of embroidery looks to both its roots in a region with longstanding embroidery practices as well as to potential sources of inspiration drawn from far beyond the immediate cultural orbit of the young men who made these garments. Along with an exploration of the dramatic use of color, abstract pattern, and distinctive media, I offer here a somewhat speculative—yet tantalizing—analysis of the figurative imagery that adorns Ghana boy garments. I also address the role of innovation—a key element of fashion—in the production of tilbi boubous, a genre that appears to epitomize the stasis that ostensibly separates tradition from fashion. I conclude with a brief discussion of two creators of other embroidered fashions, both of whom work in Mali’s capital, Bamako. Their technical and formal innovations take the medium in new directions, while retaining its close ties to local histories and aesthetic systems.

Fashion across Cultural Borders

Although they are widely divergent in style, Ghana boy tunics and tilbi boubous share many characteristics. The medium and the basic form are similar: both are made of cotton cloth, minimally tailored, and adorned with embroidery on front and back. Their functions and sources of inspiration have much in common as well, as both are made by and for men to be worn as status symbols; both emerge from histories of trade; and both incorporate iconographic elements that refer to the sources of their wearers’ status. In addition, both are fashion, an assertion that appears to run counter to the relative conservatism of the tilbi’s style and history. Consideration of these two dress practices together illuminates the diverse contexts in which the innovation that is fashion’s distinguishing attribute may thrive.

My interpretation of Ghana boy embroidery as indigenous fashion focuses on the social context surrounding the garments, which provides insights into the motivations of their makers. I elucidate this distinctive form of embroidery using information gathered through interviews and observations in Mali, historical documentation of trade and labor migration, and stylistic and iconographic analysis of the garments. The historically important tilbi style of embroidery illuminates the primacy of embroidery in the region and the long history of dress innovation of which Ghana boy embroidery is but one vivid example. The contrast between the tilbi and Ghana boy tunics draws attention to the dramatic originality of Ghana boy embroiderers, and it also provides a framework within which to recognize the subtle but significant innovations of the embroiderers who create tilbi boubous. The relative conservatism of the latter style may, in fact, help to explain the remarkable inventiveness of the former. Both types of garments must be understood as manifestations of embroidery’s special role in the Inland Niger Delta region, and of the history of cosmopolitanism in the region, where for centuries people and goods have moved vast distances across ethnic, regional, and colonial boundaries.

Ghana boy tunics are adorned with embroidered figures, words, and abstract patterns, all articulated using bold running stitches in brilliant colors. They are a product of the specific context of West African labor migration between an arid inland region and the forested coast, as they were created by young Malian men who traveled to Ghana in search of work. These garments have stories of travel, translation, and tradition stitched onto their surfaces, stories that are both universal and highly specific. Their protagonists, young men who used sartorial creativity to set themselves apart and mark their special status, can be found in many cultures and contexts. These young men have been known by various names: “Jaguars” in some parts of West Africa and “Ghana boys” or kamalen bani in Mali. In Western as in African cultures, these young men are quick to create new styles of dress in order to distinguish themselves from their elders and their juniors, marking the distinct phase of newfound adulthood. Their innovative styles of dress reflect all that is new: new influences, new technologies, and new desires.

A brief description of one Ghana boy tunic provides an introduction to the style and iconography of the genre. This elaborately adorned garment, acquired in Djenné in the early 1990s, typifies the color, medium, and combination of figurative and abstract imagery that characterize many Ghana boy garments. Registers of brilliantly colored geometric patterns follow the simple cut of the tunic across the shoulders, down the center front and back, around the neckline, and along the fringed bottom. Red pompoms and a halo of embroidered patterns adorn the two pockets, and two more pompoms emphasize the V-shaped neckline.

Amid this vibrant abstraction, four figures have been carefully articulated using thin black outlines and broad fields of color. Two female figures on the front of the tunic are seated cross-legged, wearing miniskirts and halter tops, large earrings, and platform shoes. They have long legs, carefully styled hair, and darkly rimmed eyes that seem to indicate the use of cosmetics. Behind them float two Malian flags, each marked with the stitched word “Mali.” On the top left shoulder of the tunic, other words have been stitched into the plain cotton fabric: “Ghana, Accra.” Finally, the reverse of the tunic is adorned with two equestrian figures, one male and one female. They wear platform heels, bellbottom pants, wide-collared shirts, and carefully coiffed hair. The female figure brandishes a pistol, and both horses have one leg in the air as if captured in mid-trot. Beneath the horses, small numbers appear. Like the place names, the numbers seem to provide further information, adding to the specificity of the depiction. Each aspect of the adornment of these tunics reflects the particular history from which they emerged. Instead of a longstanding tradition, they represent novel experience, and the perception of the “exotic.”

FIGURE 1.1. Ghana boy tunic, collected in Djenné, Mali, 1993. Private collection.

FIGURE 1.2. Detail, Ghana boy tunic, collected in Djenné, 1993. Private collection.

The second type of garment, the tilbi, is firmly rooted in the perpetuation of precedent rather than in adventure and novelty, in orthodox religious practice rather than in social innovation. The tilbi is particularly associated with the cities of Timbuktu and Djenné. In the Inland Niger Delta, the tilbi style is distinguished from other boubous by its complex embroidery techniques and distinctive vocabulary of motifs, which are arranged in precise compositions in which the size and the location of the designs on the fronts and backs of garments follow longstanding precedent. They are associated with maturity, piety, and respect for established status systems.

While they are produced in the same region, and worn in the same communities, potentially even by the same people (though at different stages in their lives), these two styles of men’s embroidered garments diverge dramatically in context and intention. One is an icon of continuity and the longstanding practices associated with tradition, the other of the ephemeral trends that are the hallmark of fashion. The tilbi is a symbol of local expertise, of practices and beliefs that are conceptualized as unchanging; in principle, a tilbi made today is the same as a tilbi made a generation or a century ago. If a tilbi’s embroidery is the work of a cultural insider, steeped in the complexities of a long history of precedents, the patterns and images stitched onto Ghana boy tunics might be interpreted as the vision of a tourist, reporting encounters with distant places and people. The perception of these garments as either “traditional” or “fashionable” is central to their value as cultural capital, and to the forms of status that accrue to their wearers.

Setting the Stage for Fashion: Labor, Trade, and Travel in Mali

The Inland Niger Delta region is defined by the curve of the Niger River as it reaches its northernmost point near the Sahara Desert and begins its journey south. The trade center Mopti is the major city in the region, located at the confluence of the Niger and Bani rivers. The historically important cities Timbuktu and Djenné are also located in the region, along with the Bandiagara cliffs and plains, closely associated with the Dogon people. In her analysis of trans-Saharan commerce in the nineteenth century, Ghislaine Lydon emphasizes the cultural diversity of the region and its long history of trade networks: “One must think of the Sahara as a dynamic space with a deep history. It was a contact zone where teams of camels transported ideas, cultural practices, peoples, and commodities.”1 Timbuktu, established in the twelfth century, and Djenné, which has been continuously inhabited since 200 BC, had both emerged as the region’s leading trade centers by the time North African chroniclers recorded their impressions beginning in the fifteenth century.2

Trade across the Sahara to the north, and with the goldfields and rich agricultural regions to the south, brought great wealth to the Inland Niger Delta during its heyday in the tenth to fifteenth centuries, before the Portuguese and others sailed ar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Fashion Matters

- 1 Indigenous Fashion: Embroidery and Innovation in Mali

- 2 Nubia in Paris: African Style in French Fashion

- 3 Reinventing Local Forms: African Fashion, Indigenous Style

- 4 Conceptual Fashion: Evocations of Africa

- 5 Fashion Design in South Africa: Histories and Industries

- Conclusion: What Fashion Shows

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index