![]()

1 “They Think We Can Manufacture Crops”

Contract Farming and the Nontraditional Commodity Business

IN MAY 1994 I sat at a meeting in the office of a large international development organization in downtown Banjul, the small capital city of The Gambia, West Africa. The conversation centered on the need to diversify the country's exports and its dependence on groundnuts, a traditional export crop whose annual export earnings had been declining for the past decade. The discussion eventually turned to how The Gambia, with its favorable climate, political stability, low labor costs, and relatively close proximity to European markets, could increase its role in the growing fresh fruit and vegetable and cut flower trade to Europe, an activity that already had achieved some success. A glossy, colorful brochure financed by a British aid agency was handed out; it included the caption “Cut Flowers, The Gambia: An Opportunity to Invest” (Commonwealth Secretariat and the National Investment Board, n.d.). Key questions raised at the meeting included (1) how could contract farming of “nontraditional” exports commodities (green beans, chilies, and cut flowers) play a role in this trade; and (2) how could beneficial links between Gambian farmers and international markets and businesses be forged?

Later in that same year I attended a similar meeting in Accra, Ghana, where policy makers again were praising the benefits of export diversification and the nontraditional export trade to Europe, which both were perceived as mechanisms for bolstering the country's economy and alleviating poverty. In this case it was argued that the country had relied too long on traditional export commodities such as cocoa, whose trade volume had improved little in recent years. Once again, the export of nontraditional commodities (NTCs) to lucrative markets in the West (Europe and the United States) was viewed as a means to diversify exports and achieve economic growth. The kinds of discussions at this and the Banjul meetings were not without financial consequences, as millions of dollars of development funds at the time were chasing nontraditional commodity programs in Africa, often relying on contract farming models for implementation. They were (and still are) pursued in the hopes of diversifying exports, enhancing the so-called private sector, and improving the welfare of small farmers by linking them with transnational firms (Helleiner 2002; World Bank 2007a).

In its most basic terms, contract farming (CF) involves the production of a commodity by a farmer under an agreement with a buyer, usually an agribusiness firm or food processor, at an agreed price and quantity. It has long dominated the agrarian landscape in high-income countries, such as the United States, but in the 1990s it was a relatively recent innovation in sub-Saharan Africa, where it remains both widely praised and strongly criticized (see Little and Watts 1994; Glover and Kusterer 1990; Sautier et al. 2006). In Africa CF operations sometimes are married with the production and trade of an NTC, which is defined as “a product that has not been produced in a particular country before…[or] was traditionally produced for domestic production but is now being exported” (Barham et al. 1992: 43). USAID alone supported more than twenty-five NTC programs in Africa during the 1990s that focused on niche markets, such as French beans, spices, and mangoes and pineapples, and often involved a contract farming model of production and marketing (Little and Dolan 2000; Ghana Private-Public Partnership Food Industry Development Program 2003). Like the community-based conservation programs that will be discussed in chapter 3, these ventures seemed like “win-win” situations: low-income African farmers gain access to advanced technologies and high-income markets, and private corporations and governments profit from cheap labor, abundant land, and favorable growing conditions.

Despite a very mixed record of delivering benefits to farmers in Africa, contract farming of NTCs is viewed as a “fresh hope for Africa's declining agriculture” (World Agroforestry Centre/NEPAD 2007: 1). In this chapter, I examine the experiences of contract farming of NTCs in the Banjul (The Gambia) and Accra regions (Ghana) of West Africa, both sites where horticultural exports and CF were strongly advocated and backed by international financial institutions and development agencies. In the early 1990s both countries were undergoing major economic reform and export diversification programs, and contract farming of NTCs was seen as integral to these efforts. Similar NTC programs were taking place in several other countries on the continent at the time, including Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Burkina Faso, with the same Panglossian rhetoric about the benefits of CF farming and NTC trade. At the time the enthusiasm seemed warranted as exports of fresh fruit and vegetables from Africa to Europe were growing rapidly in the 1990s, especially during winter months, when European-grown produce disappears from the market (see Little and Dolan 2000; Little and Watts 1994). In practice, however, these were targeted investments for particular locales that took advantage of Africa's climate, cheap labor, abundant land, and donor financial incentives, but proved to be especially risky for smallholders.

By capturing the historical moment when farmers in both locations were first being introduced to contract farming of NTCs, the chapter assesses its local impacts on farmer welfare and labor relations; the ways that governments and development organizations (including NGOs) latched on to “niche markets” for NTCs as solutions to the two countries’ economic crises; and the contradictions between the narratives of policy makers and the local realities of CF. It also addresses recent challenges to CF and horticultural exports presented by the growing dominance of supermarkets, new certification requirements for food imports from Africa, and changing consumer preferences in Europe.1 Some of the unsustainable aspects of smallholder involvement with NTCs first observed in the early 1990s created problems throughout the decade and into the 2000s and eventually derailed what was seen by many as a promising union between small farmers and international business (Glover and Kusterer 1990; Little and Watts 1994).

The chapter will show that one country (Ghana) saw its exports of NTCs grow rapidly in the 1990s and 2000s, although accompanied by a sharp decline in the use of smallholders and contract farming. By contrast, during the same period The Gambia experienced a decline in both NTC exports and reliance on contract farming and small-scale farmers. The development narrative that small-scale farmers would greatly benefit from a close integration with multinational business and its modern technologies and management practices proved to be overly naïve regarding the economics and politics of CF, demands of global markets, and incentive structures of transnational firms themselves. In both the Ghanaian and Gambian cases large agribusiness firms and commercial farms moved away from contracting with smallholders and, instead, have expanded production of NTCs on their own large farms. As will be emphasized, this shift partially results from the imposition of stringent certification and food safety requirements by European importers and supermarkets that made very costly the monitoring of produce from smallholders, but the trend away from smallholder contracting was well underway even before this, including in Kenya and other African countries (see Dolan and Humphrey 2000; Okello et al. 2007; Minot and Ngigi 2004; and Sautier et al. 2006).

Another factor that accounted for the demise of small farmer contracting was the liberalization of land markets in both locations, which reduced the costs of land acquisition and allowed large farms to expand at the expense of smallholders. The cumulative effect of these forces further reduced the role for small-scale farmers in the NTC business (see Dolan and Humphrey 2000). The declining trend in the use of CF in the NTC export trade occurred despite the continued praise for contract farming and its benefits in development and government policy circles (Ghana Private-Public Partnership Food Industry Development Program 2003; World Agroforestry Centre/NEPAD 2007). Finally, as will be shown in the case of Ghana, small farmers ironically have been brought back into the NTC business because of strong state support and public investment programs, both pariahs of the neoliberal reform era but critical elements of the Ghanaian success story.

The Historical Context

The language and classification process of NTCs reflect a set of global changes that are closely associated with free trade policies and the structural adjustment programs that were discussed in the introduction.2 This observation is especially relevant to Ghana and The Gambia, which were among the first “adjusters” on the continent to undergo wide-ranging structural reforms in the early 1980s. In the hopes of increasing trade revenues and reducing the state's role in agriculture, development agencies and their dependent African states heavily pushed for private-sector-led export diversification and NTC programs (see Mannon 2005; Minot and Ngigi 2004; World Bank 1989; Humphrey 2004). As implemented in practice, the concept of an NTC is ripe with contradictions and uncertainties since what constitutes a nontraditional export product changes both within and across national boundaries. For example, under a USAID trade program in Ghana in the 1990s the yam, a tuber crop indigenous to West Africa and a local food staple, is classified as a nontraditional export. On the other hand, cocoa, an industrial commodity introduced by the British in the last century, is considered a traditional export.

The contradictions are even sillier in East Africa, where in Uganda coffee and cotton are labeled as traditional products, but maize and some varieties of local beans qualify as NTCs because they have not been exported to overseas markets in the past. The whole range of “exotic” produce (for example, mangoes), high-value horticultural products (for instance, green beans and cut flowers), and spices—the so-called niche crops that have received such a strong endorsement from the World Bank (World Bank 1994 and 2007a)—mainly fall into the category of non-traditional. The dividing lines, however, are often blurred, and business entrepreneurs and politicians have been known to petition the government, often via an export promotion unit, to have a certain product reclassified as a nontraditional export in order to receive a subsidy or credit. Since the export of NTCs in such countries as Ghana is exempted from government export tariffs and is eligible for tax rebates, there are strong incentives to pursue this strategy (see Takane 2004: 31). Thus, a planner with one mark of a pen can reclassify an entire commodity regime, its farmers, and traders into a category worthy of investment and promotion and, as well be discussed later in the chapter, instigate agrarian changes with widespread social and political implications.

The notion of a NTC takes on a whole set of powerful associations in states such as Ghana and The Gambia. Table 1.1 lists some of these hidden attributes that were implicitly endorsed by the economic reform programs of the 1980s and 1990s. While production and trade in traditional export commodities, such as groundnuts (The Gambia) and cocoa (Ghana), symbolized the old statist policies and “backward-looking” programs of agriculture, the NTC business is seen as progressive, export-driven, and entrepreneurial. In short, it signifies a new market-savvy Africa with linkages to transnational companies, fiscally conservative budget reformers, and true believers in the benefits of global commerce.

Table 1.1. Nontraditional versus Traditional Export Commodities

| Nontraditional Commodities | Traditional Commodities |

| Private sector | Government |

| Progressive | Backward |

| Globally market-driven | Government monopoly |

| Assist economic reforms | Hinder economic reforms |

| Pro transnational corporations | Pro state-owned corporations |

| Wave of the future | Wave of the past |

Source: Adapted from Little and Dolan (2000: 62)

The decade of the 1980s witnessed rapid increases in the involvement of low-income African farmers in the production of NTCs, including in Ghana and The Gambia. As prices for classical export crops, such as sugar and cocoa, fell throughout the decade, many farmers, with the active encouragement of their governments and development agencies, pursued high-value niche crops. In The Gambia, for example, the percentage of total foreign exchange earnings from groundnut exports fell from 45 to 12 percent from 1981–82 to 1991–92 (Hadjmichael et al. 1992). Although not as dramatic as the Gambian case, foreign exchange earnings from Ghana's traditional exports, including cocoa and gold, declined throughout the 1980s (ISSER 1992: 77). Confronted with these dismal trends, both states, with funding from international development agencies, pursued NTC production and export diversification programs. This often meant significant transformations in the organization of production and marketing among smallholders, including the promotion of linkages with agribusiness through contract farming mechanisms (see Little and Watts 1994).

In high-value commodity chains contracts are used to vertically integrate farmers into the market, ensure that there are regular supplies and a reliable market outlet for the commodity that is produced, and facilitate transfers of technology and inputs between growers and contracting firms. The underlying premise is that a contract is required for farmers to take on the added risks associated with a new crop and an unfamiliar and often very distant market. It also helps to ensure that the buyer has a predictable, reliable supply of the product. Contract farming is a common agrarian institution in high-income countries like the United States, but in places like Africa it is part of recent transformations in global commodity systems and trade. In its early stages contract farming arrangements between smallholders and large firms and farms were integral to Ghana's and The Gambia's horticultural export trade.3 In the case of the Accra area the main NTC grown by smallholders was pineapples, and in the Banjul region it was vegetables and fruits, mainly eggplants, chilies, green beans, and mangoes.

The growth in NTC exports from sub-Saharan Africa during the past twenty-five years, including from The Gambia and Ghana, is best illustrated through an examination of the global fresh fruit and vegetable (FFV) industry. This sector has involved strong participation both by agribusiness firms and African smallholders. The destination for most of Africa's horticultural produce, including FFVs from The Gambia and Ghana, has been Europe. Aggregate exports from sub-Saharan Africa showed large annual increases during the 1990s, especially from Kenya, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, but large declines in the 2000s (World Bank 2007a). Part of the reason for the recent drop in FFV exports from sub-Saharan Africa is the emergence of Morocco and Egypt as key exporters of winter vegetables to Europe. These two countries hold considerable transport advantage, with their close proximity to Europe, over sub-Saharan African locations and, consequently, have taken over a large percentage of market share (World Bank 2007a: 6).

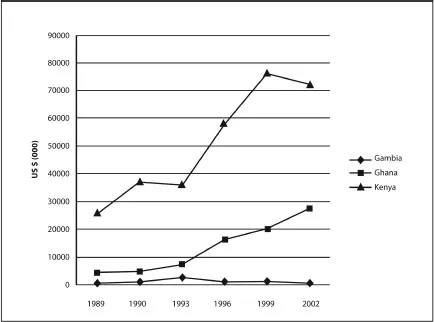

In terms of The Gambia and Ghana, table 1.2 shows the export record for FFVs in the countries also is mixed. For comparative purposes, data from Kenya, which is one of Africa's earliest and most important exporters of FFVs, are included in the table. Overall FFV exports (mainly pineapples) from Ghana continued to grow during 1989–2002, but declined in The Gambia by almost 75 percent during 1993–2002. The Gambia, which was one of the early participants in the trade, clearly has not kept pace and has lost market share to other West African countries, including Mali and Burkina Faso (see Friedberg 2004), and the above-mentioned North African competitors. In addition to the increased competition from nearby countries, other reasons for The Gambia's poor performance include decreased air and sea transport links to Europe; the increased demands for certification and product safety by European importers; and widespread financial problems among export firms. In contrast to The Gambia, the export market in Ghana has benefited from a growing demand for its main NTC export, pineapple; its demand in Europe grew at 5 percent per annum during 2000–2003 (Ghana Private-Public Partnership Food Industry Development Program 2003: 8).

Associated with the emphasis on nontraditional exports were extensive changes in the economic policies of African states and the international donors that supported them. As was discussed in the introduction, in the decade of the 1980s national governments in Ghana, The Gambia, and several other African countries confronted both nightmares of national bankruptcy and an international community that viewed excessive state intervention as the main problem. The decade marked the beginning of a radically different approach to development. The economic reform programs introduced in The Gambia and Ghana during 1983 initiated some of the earliest and most comprehensive pro-market policies on the continent. For The Gambia this meant strong reductions in fertilizer subsidies for rice production, the country's key food staple, which resulted in reduced fertilizer imports from 5,500 to 600 tons from 1984 to 1990, a steep fall in domestic production, and a growth in rice imports of more than 300 percent in that period (Mosley, Carney, and Becker 2010). Since the reform programs in both Ghana and The Gambia were instigated and supported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, they went by the same name, the Economic Recovery Programme (ERP). indeed, the IMF and World Bank were driving forces, and NTC export activities found a prominent place in the reform packages in both countries. The importance of production and marketing flexibility and the perceived failures of the state in most agricultural export ventures were stated reasons for a new private-sector-led strategy (see World Bank 1989 and 1994). Both countries had large state-owned juice-processing companies that failed in the 1980s, only to be replaced by private-sector initiatives during the 1990s. As will be shown, the market-led reforms in The Gambia and Ghana sharply increased the role of the private sector in key export industries, especially in the FFV trade.

Table 1.2 Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Exports, 1989–2002

Source: FAO Trade Statistics (1989–2002).

Strong fiscal and other incentives encouraged investment in the production of NTCs, and by the early 1990s both Ghana and The Gambia established export promotion councils and regularly participated in European trade shows to promote their exports. In The Gambia one marketing campaign included a picture of a ripe mango and eggplant on its promotion brochures, with the caption: “The Gambia means more than beautiful beaches and friendly people” (field notes, May 1993). The Gambia is well known as a winter escape destination for Europeans, especially British tourists, but it also wanted recognition for its exports of fresh fruits and vegetables. For both countries the NTC business was to usher in a new era of “catalyzing export diversification towards more sophisticated sources of advantage” (Ghana Private-Public Partnership Food Industry Development Program 2003: 3).

The Push for Nontraditional Commodities

The promotion of NTCs in Ghana and The Gambia, therefore, occurred against a backdrop of sweeping economic reforms that reduced the state's role in agriculture and elevated the participation of the private sector. It should be noted here that the term “private sector” and its meaning are especially problematic in the context of many economic activities, including the NTC business (also see chapters 3 and 7). In the Gambian case, many of the small export firms had strong investment from key government officials, the same individuals who were publically deciding on public support and policies to promote NTC exports. Like many NTC firms in Ghana, they also depended heavily on extension services, infrastructure, and market concessions from the government (see Little 1994). The idea that the private sector can somehow be neatly distinguished from the public sector simply is incorrect, whether one is speaking of the actions of an NTC contracting enterprise or an NGO (see chapter 3). Ghana and The Gambia both were held up as success stories of good economic adjuste...