- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In cities throughout Africa, local inhabitants live alongside large populations of "strangers." Bruce Whitehouse explores the condition of strangerhood for residents who have come from the West African Sahel to settle in Brazzaville, Congo. Whitehouse considers how these migrants live simultaneously inside and outside of Congolese society as merchants, as Muslims in a predominantly non-Muslim society, and as parents seeking to instill in their children the customs of their communities of origin. Migrants and Strangers in an African City challenges Pan-Africanist ideas of transnationalism and diaspora in today's globalized world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Migrants and Strangers in an African City by Bruce Whitehouse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE AVENUE OF SERGEANT MALAMINE

Quite little is known about the life of Malamine Camara. He was born in Senegal around the mid-nineteenth century, served as a soldier for France, and died young, probably in his thirties. His brief career in colonial service, however, made a tremendous mark on what became France's Congo colony. Like his white commanding officer who orchestrated France's claim to the region in the 1880s, Malamine Camara was present at the creation of the Congo colony and was instrumental in safeguarding it against encroachments by rival powers. And, like his commanding officer, he was esteemed by his fellow explorers, celebrated by the French press, and decorated by the French government. Unlike his commanding officer, however, within a few decades of his death he was virtually forgotten: all that bears his name in the Congolese capital today is a narrow, unpaved street running through the Poto-Poto market. During my Brazzaville fieldwork in 2005, no sign indicated its official designation known by a few of my informants: l’Avenue du Sergent Malamine. The story of this street's namesake reveals the extent to which, over more than seven decades of European colonial rule, the origins of France's Congo colony were intertwined with West African migration to the region.

West Africa and Its Laptots

For centuries prior to colonization Africa's Atlantic coastline had been an area of contact between Africans and Europeans. Portuguese ships arrived on the shores of what is now Senegal in the 1440s, and the transatlantic slave trade began shortly thereafter. The coastline between the port city of Saint-Louis, near the mouth of the Senegal River, and Gorée Island hosted a succession of Dutch, British, and French trading outposts until France gained exclusive rights in the early nineteenth century. By that time the French had recruited generations of men along the Senegalese coast to work alongside their traders, merchant sailors, and military personnel. These African workers, known as laptots, were “jacks-of-all-trades,” doing everything from domestic chores to providing security for French trading posts and vessels on the Senegal River, where the trade in gum Arabic dominated interaction between locals and outsiders (Manchuelle 1987, 1997).

Te term “laptot” is, according to Curtin (1975:114), “a Gallicized form of the Wolof term for sailor, and it originally had the same meaning in French. In time, however, it shifted to mean any African who worked with the Europeans, whether as a sailor, soldier, clerk, or administrator.” Laptots were usually recruited in Saint-Louis to serve two-year contracts. Some were slaves whose Senegalese masters collected half their earnings. The French also bought slaves to serve in their army; these were often Bamanan from the interior, who as outsiders were less likely to fraternize with local populations. One of the greatest advantages to hiring Africans as troops and sailors was their resistance to the endemic diseases that wrought high mortality rates among Europeans in Africa until well into the twentieth century. Since it would have been too costly for European powers to send large numbers of their own troops to the continent, recruitment of indigenous men was the most expedient alternative. As early as 1827 these men served French colonial conquest when 200 Wolof troops were dispatched to Madagascar; 220 were sent to Guyana in 1831. The French army established an infantry unit of tirailleurs sénégalais (Senegalese riflemen) in 1857, which by the end of the century comprised more than 8,000 men. The terms tirailleur, laptot, and Sénégalais are used interchangeably in French literature from the period to designate West African personnel in colonial service.1

For years Wolof men from the coast dominated laptot work. After advancing to higher-status positions within the mercantile establishment, they were replaced by men from farther inland, particularly of Bamanan, Tukulor, or Soninke ethnicity who had migrated to the coast in search of wage labor. Soninke men were particularly numerous among the laptots and, by 1872, held most of these jobs. Laptots’ wages, starting at 30 francs per month, were quite competitive—even compared to wages paid in France at the time—and generally attracted men of noble birth seeking to use their earnings to compete for status back home by investing in agriculture and purchasing slaves to work on their farms.2 In fact, the French were frequently irritated by laptots' tendency to quit their service even before their contracts were complete to put their earnings to use. Thus Manchuelle (1997) concludes that, far from being coerced into migration by repressive policies such as head taxes and forced labor (which began much later in the West African colonial enterprise), these men should be considered “willing migrants”—a notion to which I will return.

Laptots serving aboard French naval and commercial vessels could sail to French forts at Grand-Bassam and Assinie in the future Côte d'Ivoire, to posts established along the Gabonese coast of Central Africa, and even as far as France. Some of these men learned local languages during their service and acted as interpreters for their French employers in parts of Africa quite distant from their native lands. Sergeant Camara was only one of many laptots who served in Central Africa before the official onset of France's colonial conquest of the region.

Claiming the Congo

In January 1880 a dozen laptots were recruited in Dakar for an expedition to Gabon. Camara was among them. They were to accompany a handful of Frenchmen led by a twenty-eight-year-old, Italian-born French naval officer named Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza. Brazza had already conducted one Central African expedition, during which he spent nearly three years trekking through equatorial forests with another mixed Franco-Senegalese contingent in hopes of finding a route up the Ogowé River to the continent's interior.3 Although he never found such a route, merely surviving the ordeal gained him renown across Europe. Upon his return to France in early 1879 Brazza was feted by various European leaders including Belgium's King Leopold II, who was eager to establish a colony of his own in the Congo Basin.

The mission Camara had joined, Brazza's second, was funded in part by the French chapter of King Leopold's Association Internationale Africaine, ostensibly a humanitarian and scientific organization, and in part by the French naval ministry. The expedition arrived on the shores of Gabon in March 1880 and three months later established a French outpost on the upper Ogowé River. It then pressed on overland to the Congo.

It was during this trek that the party met an envoy of Makoko Iloo I, a king of the Téké people who soon signed a treaty granting Brazza possession of certain lands on the right bank of the wide section of the river known as the Pool.4 The “Makoko treaty” became the foundation of French colonial rule in the Congo Basin. Brazza wrote the document (which neither the king nor any of his aides was able to read) as a cession of territory, and three weeks after signing it he set up an outpost at M'Foa, on the Pool's right bank, flying a French tricolor to be visible to boats on the river. Before returning to the coast, Brazza instructed his men at M'Foa to show a copy of the treaty to any European who arrived.

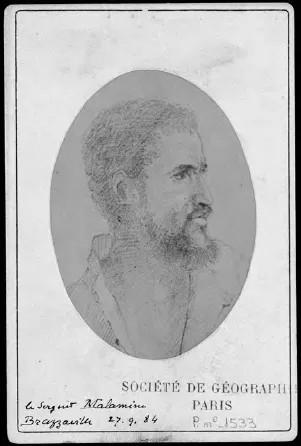

Figure 1.1. Sergeant Malamine Camara as sketched by Charles de Chavannes in Brazzaville, September 27, 1884. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE SOCIÉTÉ DE GÉOGRAPHIE, PARIS

The tiny detachment Brazza left behind was an unlikely group to represent the French Republic in its newest territorial acquisition. It consisted of a freed Gabonese slave and a Senegalese laptot under the command of Sergeant Malamine Camara. Malamine, as he became known, had already served with distinction during the voyage from the coast, learning local languages including Téké, which was widely spoken west of the Congo River. During the more than eighteen months that he commanded the M'Foa outpost, Malamine hunted buffalo, hippopotamus, and elephant, using a local musket when his Winchester rifle's cartridge supply ran low (Chavannes 1929). He distributed meat to his subordinates and to local political leaders as a goodwill gesture. His resourcefulness was noted by many observers, not least by local inhabitants who nicknamed him Mayélé (meaning a brilliant mind or resourceful character), as well as Tara Nyama (“meat father,” for his gifts to their chiefs). Charles de Chavannes, Brazza's personal secretary and eventually a governor of colonial Congo, later described Malamine in the most glowing terms:

The meager resources that his leader had left him were indeed small in comparison with those born of his ingenuity of spirit, his remarkable physical prowess, his hunting skill, and his initiative, which allowed him to handle all situations. It took only a few days for him to be profitably known by the whole region and to win the friendship of chiefs upon whom he bestowed the fruits of his hunts, venison and ivory. All the villages now kept the French tricolor hoisted; Malamine was at home everywhere. (Chavannes 1935:36; see also Guiral 1889:231)

He kept his hair braided in the fashion of the local Téké people, often wore local attire (donning his naval uniform only for exceptional circumstances), and adapted easily to the local milieu, even occasionally arbitrating disputes between local headmen.

Several months passed before Malamine was called to perform his primary duty of protecting French territorial claims to the area. In July 1881 the Welsh-born American explorer Henry Morton Stanley, now seeking to secure Central Africa for Belgium's King Leopold, arrived at the Pool with a large expedition. Stanley had spent several months overseeing the laborious construction of a road through the forest from the mouth of the Congo. Malamine donned his uniform and, accompanied by his two subordinates, went immediately to notify him of the Makoko treaty. The following description of the encounter is based on Malamine's account to Chavannes two years later:

Stanley, to impose upon [Malamine], had him surrounded with eight heavily armed Zanzibaris. Without losing his composure, Malamine planted his flag before Stanley's tent and, before saying anything to him, told [fellow laptot] Samba Thiam in his Tukulor language (incomprehensible to anyone else present), “I don't think anything serious will happen, but if it comes to gunfire, don't shoot at the blacks, shoot at the white man.” Fortunately, nothing happened and Malamine, after informing Stanley of the treaty signed with Makoko, could offer some modest gifts of fresh food to Stanley, Braconnier, and the other Europeans before returning to his post. (Chavannes 1935:142)

Malamine's actions preempted the American's attempt to claim the Pool's right bank for King Leopold. Stanley, who normally had little regard for dark-skinned natives, described Malamine as

a dashing looking Europeanized Negro (as I supposed him to be, though he had a superior type of face), in sailor costume, with the stripes of a non-commissioned officer on his arm.…[He] spoke French well, and his greeting was frank and manly…. A very short acquaintance with the sergeant proved to me that he was a superior man, even though he was a bronzed Senegalese. (1885:292–293)

Impressed by the sergeant's sense of duty, Stanley wrote that Malamine was “in his proper element among these Africans, who were of a lower grade than himself, and very tactfully and subtly he acted on his master's instructions” (ibid . , 2 9 3).

In fact, Malamine exceeded those instructions to the point of becoming a thorn in Stanley's side. Besides following his orders from Brazza to the letter, the Senegalese sergeant conducted a disinformation campaign throughout the area to prevent Stanley from winning over local populations. Stanley later wrote,

What fables Malameen [sic] uttered about our fondness for meat of tender children will never be published perhaps; but the effect of what he told [villagers] was known when the crier beat his tom-tom in the night, and shouted out along the river bank and amid the huts of the scattered village that [a local chief] had resolved that none of the people should speak with us, or sell us anything any more. (1885:299)

The mere existence of the Makoko treaty may not have dissuaded Stanley from trying to make inroads into French-claimed territory: he put little stock in the document, which was invalid under international law until it could be ratified. Malamine's operation to blacken his name, however, deterred Stanley for several months. It was not until New Year's Day 1882 that Stanley again crossed the Congo from his encampment aboard a newly assembled steamboat, the first of its kind in the area, with several Zanzibari mercenaries. He landed at M'Foa, perhaps hoping his show of force would convince Malamine's small contingent to abandon its post. One fanciful French account alleges that Stanley attempted to bribe the laptots into surrendering their station to him by offering a suitcase stuffed with British pound notes but was rebuffed at gunpoint. In any event, Malamine and his men stood their ground; most reports suggest that the sergeant gave Stanley a cordial greeting and reminded him of French sovereignty over the area and of the treaty. The explorer and his men soon crossed back to their camp on the left bank of the river.5

Weeks later Malamine received word via messenger that his post was to be relieved, that France would renounce its claims in the Congo Basin, and that he should return to Gabon forthwith. Malamine had doubts about the order, which was conveyed verbally; possibly fearing a trick by Stanley, he sent word back with the messenger that he would remain at M'Foa until relieved by a French officer. The lieutenant who eventually came was struck by Malamine's diplomatic victories there: “I could easily discern that he had the sympathy of all. I highly doubt that the Senegalese's successors in Stanley Pool would achieve such tasteful popularity” (Guiral 1889:234).

Malamine's fears of a ruse were not far-fetched: King Leopold had in fact used his influence over the association funding the Congo expedition to ensure that Brazza's bothersome outpost would be quietly abandoned. A letter from Mizon, Brazza's replacement, instructed Malamine to inform the local populace that France was giving up its ambitions in the area and to return to Gabon. Suspecting that something was amiss, and not wishing to disobey Brazza's original orders, he instead mounted a covert public relations operation unbeknownst to the lieutenant who had come bearing Mizon's orders. According to Chavannes (1935:40),

[Malamine] never told the natives about the decision to pull up stakes. On the contrary, he swore to them and all the chiefs that his absence would be temporary, that he would come back with Major Brazza, and that until that day the French colors should continue to fly over their villages.

This task accomplished, the sergeant returned to Gabon, where he asked to be sent back to Senegal without delay, his contract having expired. His actions prior to departing M'Foa would have great significance for France's presence in the region.

The Mission de I'Ouest Africain

By the time these events transpired, Brazza was in France planning his third expedition. The French parliament ratified the Makoko treaty in November 1882, some six months after Malamine left the station at M'Foa, and in January 1883 the government approved full funding for another expedition. The following month a French army lieutenant arrived in Dakar to recruit the bulk of the mission's manpower. This time, instead of a mere dozen laptots, 139 were hired. The recruiter went to great lengths to track down Sergeant Malamine in Saint-Louis, as well as Samba Thiam, his former companion at M'Foa. Malamine also helped enlist other laptots, signing them to two-year contracts with 60 francs’ pay per month, a very generous salary at the time. The expedition's personnel also included 25 Algerian riflemen, 25 noncommissioned military officers of whom Malamine was the only non-Frenchman, 21 auxiliary officers including Chavannes, and a general staff of 8. Many others picked by Brazza himself, including his younger brother Jacques (a naturalist), joined the roster, along with a motley assortment of unqualified men, nearly half of whom would be sent home within months. Finally, some 165 porters known as “kroomen” or “kroo-boys” were hired (perhaps more accurately press-ganged) in Liberia to perform the heavy hauling; they were given yearlong contracts, although Brazza hoped to replace most of them with local manpower in Gabon. Unlike Brazza's previous expeditions, the Mission de l'Ouest Africain was an enormous undertaking: between 400 and 500 men took part, only 87 of them European.6

Once this mass of men and equipment arrived on the Gabonese coast in late April 1883, it took months to acquire the necessary materiel, food, and canoes to set off. Eventually the mission divided its forces: while Brazza led some of its personnel down the coast to the mouth of the Congo, others penetrated the interior along the Ogowé and Niari valleys.

Albert Dolisie, the first member of l'Ouest Africain to arrive at the Pool in November 1883, did not receive the warm welcome he had hoped for. Residents of M'Foa remembered Malamine but apparently could not recall Brazza himself. Some accounts indicate that they had not flown the French tricolor during his absence, and there were even doubts over their loyalty to Makoko Iloo, whose sovereignty over the area was more ambiguous than Europeans realized.7 Only in April 1884 did other members of the mission, including Chavannes and Jacques de Brazza, finally reach Makoko Iloo's royal court to present an official copy of the ratified treaty.

Malamine had accompanied Chavannes inland from Gabon and proved his worth wherever he went. In March 1884, wrote Chavannes (1935:142), upon recognizing the Senegalese sergeant, natives “were so happy to see him they danced with him”; “On the Congo,” Chavannes would recall, “Malamine's presence was like a password” (1929:174). He was Brazza's interpreter on numerous official occasions, including negotiations and ritual ceremonies held to win and recognize local chiefs’ loyalty.

Navigating down the Congo River, Chavannes's party found that Makoko Iloo remained faithful to his pact with Brazza: “The old chief had fully kept his word, resisting all attempts to weaken his fidelity. His immediate vassals had behaved the same way: Malamine's labor had paid off” (Chavannes 1929:175). After Makoko and his vassals ritually renewed their loyalty pledge to France, Chavannes described Malamine as “the linchpin of a long-term project of which this ceremony was the happy and formal consecration” (1929:179). Brazza and Chavannes spent several weeks in M'Foa, which was to become the new colony's administrative capital. The site, at that time just a small clearing doted with a few thatched abodes, had already been dubbed “Brazzaville.”8

On June 3, 1884, Brazza departed, leaving Chavannes in charge with Malamine as his trusted aide. Together Chavannes and the Senegalese sergeant chose sites for the construction of dwellings and administrative buildings along the riverbank; the first permanent structures were completed in September of that year. Malamine served as Chavannes's intermediary with the local populace and ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Exile knows no Dignity

- 1. The Avenue of Sergeant Malamine

- 2. Enterprising Strangers

- 3. Among the Unbelievers

- 4. The Stranger's Code

- 5. Transnational Kinship

- 6. Children of Exile

- Conclusion: The Anchoring of Identities

- Epilogue: Displaced Dreams

- Appendix 1. Notes on Methods

- Appendix 2. Survey Results

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index