![]()

Part One

The Unrestricted Use of

Natural Resources

![]()

CALUMET BEGINNINGS AND

THE BIRTH OF AMERICAN

ECOLOGICAL SCIENCE | 1 |

IT CAN BE SAID THAT THE GLACIERS MADE LAKE MICHIGAN, Lake Michigan made the beach, and the wind made the Dunes. Although there is much more along the South Shore of Lake Michigan than just the Dunes, the Dunes are what makes this part of the natural world spectacular and unique. They have inspired artists, hikers, and scientists. They are the jewels of the South Shore. They brought Henry Chandler Cowles to the area to study them and their plant life. And by doing just that, he justified the theory of succession and initiated ecological science in this country.

THE EFFECTS OF THE GLACIERS

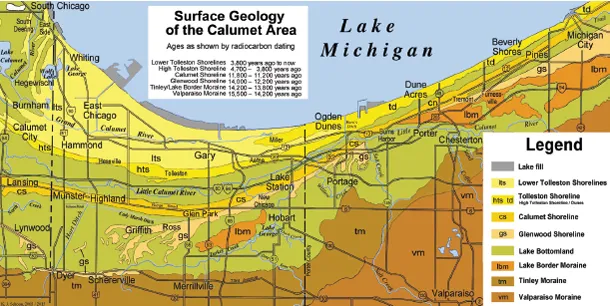

Although the glaciers have been gone from Northwest Indiana for thousands of years, much of what they formed when they were here remains and has affected the area ever since. Roughly seventeen thousand years ago, the Lake Michigan lobe of the glacier invaded the Calumet Area and deposited huge amounts of sediment along its edge, forming the ridges and hills known today as the Valparaiso Moraine (vm on the map below). The Valparaiso is the largest and highest of the moraines in the Calumet Area, and together with the smaller Tinley/Lake Border Moraines (tm and lbm on the map below), it forms one of the dominant landscapes of the area. It gets its name from the city of Valparaiso, where the moraine is narrower, higher, and steeper than in places to its west.

Later on, the glacier melted back, readvanced, and deposited the sediments that made the Tinley/Lake Border Moraines on the lakeward flank of the Valparaiso Moraine. Although many moraines were created by glaciers in what are now Indiana and Illinois, the Valparaiso Moraine is significant because it was built upon the top of the Eastern Continental Divide, which separates all rivers and streams that flow north and east to the North Atlantic from those that flow west and south to the Gulf of Mexico. Thus the divide and the moraines form the natural southern end of the Lake Michigan drainage basin.

Surface geology of the northern Calumet Area.

LAKE MICHIGAN’S ANCIENT SHORELINES

What is now Lake Michigan (but what had earlier been called Lake Chicago) was formed about 14,500 years ago, when the glacial lobe that had entered Northwest Indiana retreated from the Tinley Moraine.1 Much of the meltwaters from that ice were then trapped between the glacier to the north and the U-shaped Tinley and Valparaiso Moraines.

The Glenwood Shoreline (gs on the map) was the first and is the highest (at 640 feet above sea level) of Lake Michigan’s ancient shorelines. During the Glenwood phase a long sand spit, extending from Portage to Griffith, formed parallel to the shoreline. North of this shoreline is the flat former lake bottom containing extensive deposits of clay.

The history of the lake is quite complicated, but the important stages are described here. The Glenwood phase ended about 12,200 years ago when the melting glacier retreated past the Straits of Mackinac. As the straits were then at a significantly lower elevation than the Chicago Outlet, the lake water rapidly drained to the north, the lake level dropped by a large amount, and its waters receded from the shore. The Glenwood phase was over.

The Calumet Shoreline (cs on the map) formed about 11,800 years ago when a glacial advance again blocked the Straits of Mackinac and the lake level rose to 620 feet above sea level. In Lake County the Calumet Shoreline formed several miles north of the Glenwood. In Porter and LaPorte Counties it developed quite close to the older Glenwood Shoreline. In certain places Calumet dunes even bury those of the Glenwood. Lake Michigan’s Calumet phase lasted about 600 years, ending roughly 11,200 years ago when once again the glacier retreated past the Straits of Mackinac. The lake waters again drained to the north and the lake level once again dropped. The Calumet phase was over.

The Tolleston Shoreline, the third and youngest of Lake Michigan’s shorelines, was formed many years later when the lake level had risen to 605 feet above sea level. It was named the Tolleston Shoreline because it is so prominent in Tolleston, now a part of the city of Gary.

The High Tolleston Shoreline (from Calumet City to Portage, hts on the map) today is a thirteen-mile-long curved ridge, north of and parallel to the Calumet Shoreline. The Lower Tolleston Shorelines (from Chicago to Miller, Its on the map) were composed of more than 150 rather low parallel beach ridges. Long, low swales that often contained standing water lay between the ridges. This landscape is often called “dune and swale” topography, but it might better be called “beach ridge and swale” topography. This rare landscape can today be seen in the several nature preserves in western Gary and Hessville in eastern Hammond. The longest of these narrow dune ridges still remaining can be seen in Hessville’s Gibson Woods. The Tolleston dunes (td on the map) in Porter and LaPorte Counties, the result of prevailing northwest winds, are the tallest dunes in Indiana.

Lake Michigan’s water level fluctuates with the change of seasons and through drought and periods of above-average rainfall. In a typical year, the lake level rises approximately twelve inches in the spring and summer and then in autumn and winter falls back down to its late winter low level.2

BIODIVERSITY OF THE DUNELANDS

Because the Dunes are situated between the hardwood forests of the east and the prairies of the west, Duneland contains plants from both regions. Because wetlands lie between the Dunes, Duneland also contains wetland plants. Because the Dunes are sandy, Duneland has some desert plants from the southwest. Because the glaciers brought seeds down from the north, Duneland has some plants from the north. In fact, the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, with more than 1,574 different species of plants, has a greater number of different plant species than any other national park of similar size and more than most of the large parks such as Yellowstone and Yosemite.

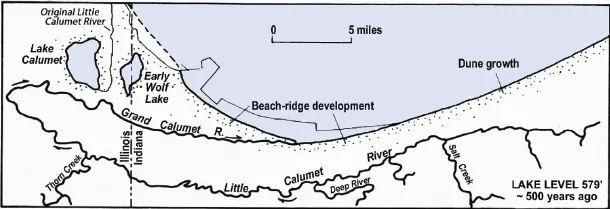

THE GRAND AND LITTLE CALUMET RIVERS

The evolution of the three Calumet Rivers was quite convoluted. In presettlement times, today’s Grand and Little Calumet Rivers were one long river that began in LaPorte County and flowed west to Blue Island, Illinois, where it crossed the Tolleston Shoreline, then flowed back into Indiana and emptied into Lake Michigan at what is now Marquette Park in Gary. Being for the most part parallel to the Lake Michigan shoreline, it had a low gradient and its waters flowed rather slowly. Close by, but separate in those days, was a “little” Calumet River that connected Lake Calumet to Lake Michigan.

Someone, or a group of people, perhaps over time but definitely before 1805, dredged a low but dry channel between the two Calumet Rivers. This may have been done by Indians or perhaps French fur traders (see General Hull’s map below). In any event, during an 1805 flood, river water poured through this low channel from the original Calumet River into that “little” river. The fast-moving river water naturally eroded the sandy channel as it flowed, resulting in a new route for the longer Calumet River. In effect, this action split the Calumet River in half, with the waters flowing through the channel and then down that “little” Calumet River to its mouth, emptying into Lake Michigan at what is now Chicago’s Ninety-Fifth Street.3

Duneland has plants from the north, east, south, and west. It is often called the Central Forest-Grasslands Transition Ecoregion.

The Calumet Rivers before the 1805 flood connected the original Calumet River to the “Little” Calumet River west of Wolf Lake. Chrzastowski and Thompson, “Late Wisconsinan and Holocene Geologic History,” 412.

General William Hull’s 1812 map. Brennan, Wonders of the Dunes, inside back cover.

By the mid-1800s the old mouth at Miller Beach had dried up and the nearly flat Grand Calumet changed directions on its own and started flowing west. The original “little” Calumet, now in Chicago, is today called the Calumet River. The lower original river (the north branch) is now the Grand Calumet River, and the upper original river (the south branch) is now the Little Calumet River.

The rivers have had three other diversions since 1805. In 1922 the Little Calumet was linked to the Illinois River system (and thence to the Mississippi River) via the Cal Sag Channel. In 1925, the Grand Calumet was linked directly to Lake Michigan via the Indiana Harbor Ship Canal. Then in 1926 Burns Ditch was dug, connecting the upper Little Calumet River with Lake Michigan. Whereas before 1805 the Calumet River had one mouth, the Calumet Rivers today have four.

All three Calumet Rivers were crystal clear when first seen by area pioneers. They provided those early settlers, and the Potawatomi before them, with wholesome food.

Today the headwaters of the Grand Calumet River are at Gary’s Marquette Park Lagoons. From there, the river flows westward to East Chicago where it is diverted and flows north to Lake Michigan through the Indiana Harbor Ship Canal. The section of the river west of the junction has little flow: the short eastern portion flows eastward to the canal, while the lower western portion flows to the Cal Sag Channel in Illinois.4 The eastern section of the river in Gary is today a manmade channel; its only tributaries are sewer discharge pipes. The Grand Calumet River is much cleaner today than it was thirty years ago, but not as clean yet as it was in 1850.

The Little Calumet River, which begins in the hills of western LaPorte County, extends westward into Illinois. At Riverdale it still makes a hairpin turn and goes north and eastward to its junction with the Grand Calumet River. The Little Calumet has two outlets: one through Burns Ditch in Porter County, and a second where the river empties into the Calumet Sag Channel.

From Thorn Creek in Illinois to Sand Creek in Chesterton, all the streams that flow north from the Valparaiso Moraine flow into the Little Calumet River. When their waters enter the river their rate of speed decreases because of the very low gradient of the river. Thus the Little Calumet has always been prone to flooding. After heavy rains, this usually small-looking river can overflow its banks an...