![]()

What is Africa to me now?

guest edited by

Bénédicte Ledent and Daria Tunca

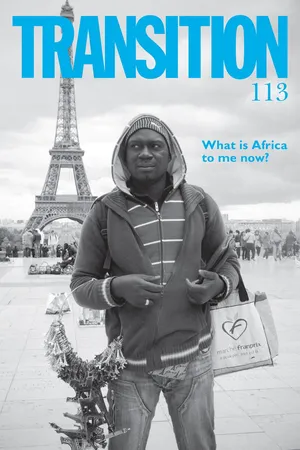

An Afropean Odyssey/Self Portrait, Ventimiglia (detail). ©2013 Johny Pitts.

![]()

What is Africa to me now?

the continent and its literary diasporas

Bénédicte Ledent and Daria Tunca

ARTISTS ATTEMPT TO capture the complexities of human nature through writing, painting, and other creative media. Academics, on the other hand, act on this impulse to understand the world by engaging in more mundane activities, such as holding conferences. And so it was that, eager to explore issues of representation, identity, and memory in the literatures of the African diasporas, we started to consider organizing an event at our home institution, the University of Liège, Belgium.

“Academia is often about academia and not about the real, messy world.”

“Explore issues of representation, identity, and memory”: our use of this erudite but hopelessly vague phrase rapidly set off our internal alarm bells, for it betrayed a seemingly in-built academic predisposition—that of examining, researching, surveying, scrutinizing an object of study, without, in the end, saying anything noteworthy (or indeed intelligible) about it. Thus, when we decided to follow through on the initial idea of organizing a scientific meeting on the African diasporas, some rather down-to-earth questions imposed themselves: what exactly were we hoping to achieve by adding yet another event to the long list of those already hosted in other institutions all over the world? How would this conference negotiate the uncomfortable chasm between the academic spheres and the world at large? “Academia is often about academia and not about the real, messy world,” the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said in an interview published in The Believer in 2009. Even as we were convinced that scholarly work did have something valuable to contribute to contemporary debates on Africa and its diasporas, Adichie’s admonishment lingered in our minds.

These concerns shaped our preliminary discussions, from which two ideas emerged. First, we wanted an event that would encourage exchanges between academics, creative writers, artists, and the general public. Second, we wished rather idealistically to address questions that were at once topical, under-explored and in need of in-depth analysis. With this relevance criterion in mind, we delineated our specific focus: the representation of Africa in the writings of authors from the ‘old’ and ‘new’ African diasporas. These two categories, at first sight, seem to speak for themselves. The former refers to the descendants of people who were displaced as a consequence of the transatlantic slave trade; the latter designates those who were born (or whose parents were born) on the continent in the contemporary period but left it either as children or as adults.

We kept coming back to the famous line written by Countee Cullen in 1925: “What is Africa to me?”

Yet, if delineating the historical differences between these two diasporas seemed easy enough in theory, circumscribing the ways in which they addressed the image of Africa in their literatures proved a more complicated task in practice. What appeared to us after some research is that, even if the continent continued to haunt many creative and critical texts produced by (and on) the old diaspora based in the Americas or in Europe, Africa had lost the prominence that it had had for the greater part of the twentieth century in favor of notions more markedly denotative of displacement or (un)belonging, whether in the Old or the New World. Quite significantly, analyses of contemporary literary texts centering on the slave trade more readily discussed the writers’ representations of history than their engagement with Africa per se, which is imbued in most cases with mythical, almost unreal qualities. In studies of the new diaspora, on the other hand, we noticed that a more concrete Africa had never ceased to occupy center stage, but its representations had surprisingly rarely been assessed through the lens of the writers’ specific geographical, cultural, or generational positions. Instead, many commentators had emphasized globalizing trends or, conversely, positioned diasporic artists as the unproblematic heirs to the strategies of historical and cultural retrieval implemented by their Africa-based predecessors. Both of these orientations found in studies of the new diaspora—‘global’ and ‘local,’ so to speak—have something valuable to contribute to the debate but, when taken separately, they present all too neatly modeled versions of twenty-first century reality. The former tendency may lead one to disregard Africa’s cultural specificities and celebrate its participation in the neocolonial world order, while the latter trend often results in the presentation of diasporic writers as epitomes of Africanness. The only way around these ideological shortcuts, it seemed to us, was to probe in more detail the intermediary positions between them.

Once we had settled on a theme for the conference, all that was left to do was to find the mandatorily catchy title for the event. Hoping to conjure our own creative spark, we considered about every pun and alliteration in the book, but we were soon forced to recognize that we kept coming back to the famous line written by African American author Countee Cullen in his 1925 poem “Heritage”: “What is Africa to me?” Because our focus was decidedly contemporary, the adverb “now” added itself almost naturally. But before we could even start basking in the glory of our three-letter find, “What is Africa to me now?”, we realized that the question had already been asked by Paul Gilroy in 2006, in an interview published in this very journal, where the author of The Black Atlantic was wondering whether today’s African Americans still wanted to identify with Africa which, he said, “functions in their dreamscape much of the time as a place from which no light can escape, as the heart of darkness, as the core of unreason.” However bleak Gilroy’s words appeared to be at first sight, the change that they signaled among black Americans warranted an updated exploration of what Africa meant to its diasporas in the twenty-first century. And in the end, it seemed rather fitting that our chosen title should have been a question handed down, not quite intact, from a creative writer to a critic, and that it should have journeyed through time and space, across the twentieth century and the Atlantic, thereby embodying the constant flux, renewal, and rehearsal of ideas characterizing the African diasporas themselves.

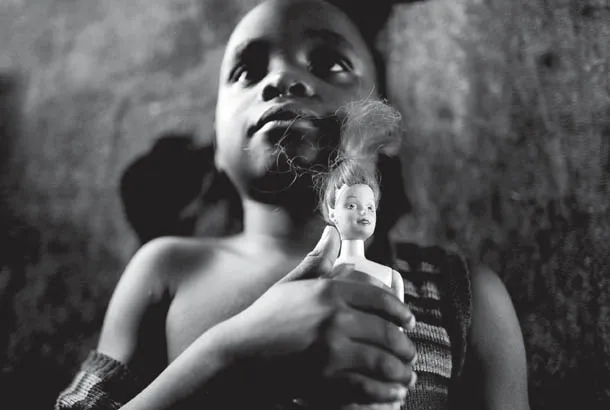

Untiled from the Grande Hotel Series. 90×60 cm. ©2011/2012 Mário Macilau.

The updated version of the question “What is Africa to me?” also imposed itself upon us for other reasons: the ambiguity of Cullen’s original poem, and the multiplicity of responses that his query had generated among members of the diaspora over the years. Thus begins “Heritage”:

What is Africa to me:

Copper sun or scarlet sea,

Jungle star or jungle track,

Strong bronzed men, or regal black

Women from whose loins I sprang

When the birds of Eden sang?

One three centuries removed

From the scenes his fathers loved,

Spicy grove, cinnamon tree,

What is Africa to me?

Africa, however distant, seems to hold the key to the poet’s understanding of his complex African American individuality.

Commentators have often underlined the pervasive tension in the text between the poet’s emotional, romanticized celebration of his ancestral Africa, and his Christian outlook on a continent whose “Heathen gods are naught to me.” Africa, however distant, is etched into the I-persona’s consciousness and seems to hold the key to the poet’s understanding of his complex African American individuality. This sentiment was famously shared by W. E. B. Du Bois who, in his Dusk at Dawn (1940), presented his connection to the continent as a cornerstone of his racial but also, even more insistently, social identity. His African ancestors and their descendants had “suffered a common disaster” and were therefore bound by a “common history”; the “social heritage of slavery” was, according to Du Bois, “the real essence of this kinship.” Du Bois is far from being the only African American intellectual to have addressed Cullen’s seminal question, which has reverberated, in call and response fashion and with different degrees of directness and nostalgia, in the work of many other twentieth-century artists based in the United States, including poets Claude McKay and Langston Hughes, or more recently, novelists Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. The idea of Africa made famous through Cullen’s interrogation and through the work of the Harlem Renaissance expanded internationally: it not only pervaded such movements as pan-Africanism and Négritude but also became a key component of the West Indian literary imagination, as epitomized in the work of Derek Walcott and Kamau Brathwaite, to mention just two well-known examples.

If the African American take on Africa is bound to be unique in the diaspora, the view of the ancestral continent held by Caribbeans and Africans is, for all their shared colonial past, to be differentiated as well.

As Abiola Irele points out in his 2005 contribution to the journal Souls, what all these thinkers—whether American or Caribbean—had in common is that “the African idea [intervened] as a mediating principle of . . . self-knowledge” and that their quest had an invariably aesthetic dimension. However, in spite of these resemblances and the similitudes in the often utopian way in which African American artists and their counterparts in the diaspora viewed Africa, it would be misleading to concentrate exclusively on the transnational success of the query and overlook the important distinctions, geographical and otherwise, between the responses that it has generated. Anglo-Kittitian Caryl Phillips reminds us of the need for such discrimination in two of his essays published in his collection Color Me English (2011). The first is a piece entitled “A Familial Conversation,” which focuses on the intellectual relationship between Martinican Aimé Césaire and Senegalese Léopold Sédar Senghor. Even though the Conference of Negro-African Writers and Artists that both attended in Paris in 1956 had “black culture” at its center, it gradually became clear that there existed a gap, “a broad gulf of unease,” between the two main groups of intellectuals present at the event, African American on the one hand, and Caribbean and African on the other. For, as Phillips writes, “Potentially, an African man and a Caribbean man have much in common, largely because for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries they were forged in the same crucible of colonial exploitation. But the African American has a somewhat different history. He has been shaped not by colonialism, but by American expansionism.” Nevertheless, if the African American take on Africa is bound to be unique in the diaspora—shaped as it is by the history of American imperialism but also by racism—the view of the ancestral continent held by Caribbeans and Africans is, for all their shared colonial past, to be differentiated as well. Such is the point of another essay by Phillips, “Chinua Achebe: Out of Africa,” where he compares his own interpretation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) as a text riddled with doubt with the more radical reading of the Nigerian writer who views the novel as basically racist. This leads Phillips to conclude that he is “not an African” but that, as someone “raised in Europe,” he is “interested in . . . the health of European civilisation” and, as such, “might have . . . overlooked how offensive this novel might be to a man such as Chinua Achebe and to millions of other Africans.”

Untiled from the Grande Hotel Series. 90×60 cm. ©2011/2012 Mário Macilau.

Obviously, the question asked by Cullen almost ninety years ago has lost none of its original relevance and power, and it has been enriched by all the different—if sometimes overlapping—perspectives that it has given rise to. More than ever now, each time the question is asked there seems to be an increasingly urgent need for it to be carefully contextualized and viewed as the expression of a singular mind rather than as a blanket interrogation whose significance is constant across time and space. This might initially come across as a paradox in the age of globalization, but ours is also a period marked by the increased idiosyncrasy of individual trajectories. Hence, even when Taiye Selasi, in her much discussed essay “Bye Bye Barbar” (2005), writes about those she calls “Afropolitans”—i.e. “the newest generation of African emigrants” who identify as “Africans of the world”—she cannot but multiply references to diverse geographical routes, varied forms of cultural expression, and dissimilar levels of social commitment to the continent. For all these differences, Selasi nonetheless insists, Afropolitans are almost programmed to “forge a sense of self from wildly disparate routes”; they—or rather “we,” for the author writes in the first person plural—“belong to no single geography, but feel at home in many.”

Who is entitled to decide what constitutes an artist’s brutally honest engagement with pressing issues, as opposed to an author’s indecent pandering to the Euro-American literary establishment?

Selasi’s essay aptly captures the cultural fluidity of the contemporary moment and offers an unusually upbeat approach to diasporic Africanness today. However, the confident, celebratory picture painted in the piece should not eclipse the more disturbing or challenging facets of African migration, be they the social disparities among members of the African diasporas, or the diversity of emotional responses to the continent expressed by the children of immigrants. Novelist Helen Oyeyemi, for example, moved to Britain with her Nigerian parents when she was four, but she hardly shares Selasi’s self-assured Afropolitan stance. In a 2005 essay revealingly entitled “Home, Strange Home,” she admits that “when it comes to Africa, I just don’t get it.” Similarly, in an interview published the same year in LIP Magazine, she confesses that “any words that I reach for in describing Nigeria are automatically and inextricably loaded with a sense of foreignness—‘vibrant,’ ‘colourful,’ ‘hot,’—it’s so close to cliché that it’s embarrassing.” This combined sense of estrangement and romanticization almost inevitably recalls Countee Cullen’s representation of the continent in “Heritage,” which may hint at an increasing convergence in the depiction of Africa between representatives of the old diaspora and some younger members of the new one.

This analogy is—and must necessarily remain—extremely partial, but it is not simply rhetorical either, for behind romanticization lurks the much debated concept of (self-) exoticization. ...