![]()

PART I

THE STORY

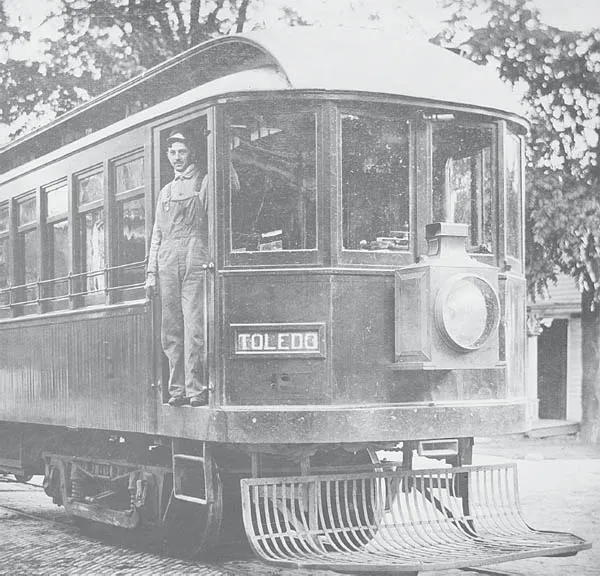

Homely though its face may be, this is the LSE’s baby picture. As the company falteringly got into business in 1901 and 1902 it relied on a fleet of rugged Barney & Smith–built interurbans inherited from the Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk. No. 8, dating to 1900, poses in Fremont about 1903. (W. A. McCaleb collection)

![]()

CHAPTER 1

GENESIS

1901 – 1903

The year was 1901, the first year of the twentieth century. Ohio’s own William McKinley was in the White House and Victoria was Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, Empress of India, and monarch of Britain’s other dominions beyond the seas — including Canada. Neither would survive the year — McKinley felled by an assassin’s bullet and Victoria of the more natural effects of age. She was 82, had reigned for 64 years, and had defined an entire age.

And in Ohio, reigning over a wholly different empire — which also included Canada — were Henry A. Everett and Edward W. Moore, two Cleveland entrepreneurs who were rapidly moving to exploit the latest and most promising technological development — the electric railway. By the dawn of the new century steam railroads overwhelmingly dominated American intercity transportation; virtually all overland travel and freight movement was by rail. To get anywhere beyond a few miles, there was no other way.

But a different kind of railroading had suddenly evolved during the decade just past. Electricity was applied to urban street railways beginning in 1888, radically changing their form and potential. Now no longer limited by the speed and stamina of horses, these street railways were built outwards from the cities over increasingly longer distances. By the mid-1890s some were beginning to link towns and cities and distinguishing themselves from ordinary streetcar lines with a new name — interurbans. By the turn of the century the development of high-voltage three-phase alternating current transmission made long-distance electrified lines practical, and proved the key to interurban expansion.

The interurbans were built to lighter standards than their steam railroad cousins and were cleaner, more flexible, and usually much cheaper to build and operate. Lines could be constructed quickly, often using existing rights-of-way in or alongside roads; when completed they usually had a ready-made business from established communities along the route, and could develop territories previously isolated by lack of transportation. For many people, the interurban offered the first practical means of mobility. The alternatives, after all, were horses, mules, wagons, carriages, and primitive roads — mud-bogged in the spring, snowbound in the winter, and rough and dusty in the best times. And even where steam railroads already operated, the interurbans offered lower fares and more frequent service. Furthermore they were more accessible and convenient, stopping at rural road crossings and delivering their passengers right to the middle of Main Street in town. Little wonder that shrewd turn-of-the-century investors saw interurbans as their route to riches. Motor vehicles? In 1901 they barely existed; only 14,800 autos were registered in the entire United States, and no trucks whatsoever. What did exist was highly expensive, and, outside of cities, had few places to operate.

There were some problems, of course. Cheap to build as they were, interurbans still required a substantial sunk capital investment. This, plus the nature of the markets, usually meant that no more than one line could be established between any two points; while two could sometimes survive, that was pretty much the upper limit. Thus anyone who wanted to reap this perceived bonanza had to move quickly to stake his claim before someone else did — otherwise it was usually too late.

The Everett-Moore group had been early and fast movers; its members, in fact, were pioneers in building true interurban lines. Their first project, the Akron, Bedford & Cleveland, was launched in 1894 and opened in late 1895. Following this the syndicate incorporated the Cleveland, Painesville & Eastern in 1895, completing it in July 1896. Later in 1895 they incorporated the Lorain & Cleveland Railway — what was claimed as the first high-speed interurban, with a route entirely on private right-of-way (excluding city entries), and cars capable of over 50 mph. It began operations in October 1897. The 27-mile-long L&C linked Cleveland with the Lake Erie town of Lorain, a one-time fishing village then on the brink of transformation into an industrial center.

By 1901 the promoters had hit full stride, taking over (among other things) the Toledo street railway system, the Detroit United Railway system serving the city of Detroit and much of eastern Michigan, plus two companies which together constituted a partially completed interurban route between Detroit and Toledo. Their original Akron, Bedford & Cleveland had blossomed into the Northern Ohio Traction Company and was rapidly expanding into the industrial and population centers south and east of Akron. Along with numerous other electric railway properties, they controlled several telephone companies and had organized the Cleveland Construction Company to build interurban and railroad lines.

A Cleveland–Toledo Interurban

Not surprisingly, the Everett-Moore group quickly visualized an interurban route between Cleveland and Toledo, which would tap a lucrative territory on its own while connecting their lines radiating from Cleveland with their Toledo and Michigan systems.

It was a bold gamble. The Cleveland–Toledo territory was a well-populated and prosperous corridor with excellent passenger potential. And already it had numerous popular Lake Erie summer resorts and parks which promised excursion business — most notably Cedar Point, near Sandusky. But there also was intense and deeply entrenched competition. The territory was dominated by the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway, a key component of the vast and lordly New York Central system. The LS&MS formed the western part of the Central’s New York–Chicago main line and operated at very high service levels. Various other steam railroad main lines and branches also crisscrossed the area.

It was bold in another way, too. Having evolved from street railways, the turn-of-the-century interurbans typically were still primarily oriented to relatively short-distance stop-and-go local business, feeling that they could not effectively compete with the faster steam railroad trains for the more profitable long-distance passengers. Most interurban managers felt that the limit of their competitive range was about 50 miles, at best no more than 75. But Everett-Moore’s planned Cleveland–Toledo line would be almost 120 miles long. The distance and nature of the competition demanded a new approach to the business, and the promoters planned to inaugurate a fast, limited-stop service with equipment capable of 60 mph.

Who were Everett and Moore, and what was “Everett-Moore” collectively? To begin with, “Everett-Moore” was a convenient shorthand term for a syndicate of what were mostly Cleveland capitalists dominated by the two principal promoters. It was not really a single monolithic entity, however; the group’s composition varied from property to property, and Everett and Moore themselves had major investments apart from one another. Most were relatively young; Everett, the senior partner, was about 43; Moore was 37. The two came from banking backgrounds and had been associated since about 1889 when they took over and electrified the East Cleveland Railroad. Among other things, they put together the Cleveland Electric Railway in 1893. Both were the picture of the turn-of-the-century entrepreneur, prematurely balding with closely-trimmed beards, steel-rimmed glasses, and highly dignified demeanors. Everett primarily concentrated on operations while Moore was chiefly interested in the financial end of the businesses. The Sandusky Register of July 3, 1901, artlessly described the syndicate and its leaders thus:

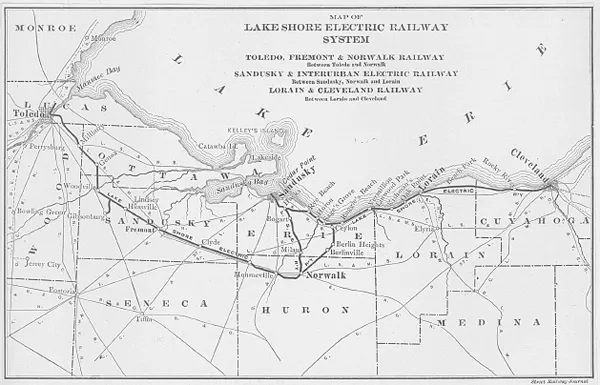

The Lake Shore Electric Railway’s original system, 1902.

Indications are the Everett-Moore syndicate is composed of about 85 men. Everett habitually chews a quill toothpick as a substitute for a cigar. He dresses to the latest fad and is immaculately clean. Moore is also well-dressed and is an entertaining companion. He does business constantly even while dressing in the stateroom of a ship and thinks nothing of working up a million-dollar deal during lunch. He works harder than anyone else in the business. Both men have charming smiles.

Big city ways apparently counted for much in Sandusky.

A principal partner in their Cleveland–Toledo project was another Cleveland financier named Baruch Mahler, universally called “Barney.” Aged 50 in 1901, Mahler began his career humbly in 1868 as a telegrapher for the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern; after associating himself with the Everett-Moore group, he helped finance the Lorain & Cleveland and served as its president from 1896 to August 1901. He was also the principal founder and president of the Electric Package Company, the Cleveland-based agency jointly created by most of the city’s interurban lines in 1898 to handle their package freight business.

Mahler took a major role in launching the new company, aided by a promising young banker named Frederick W. Coen. Only 29 years old in 1901, Coen first caught the Everett-Moore group’s eye when he was helping to put the faltering Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk interurban in better financial order in 1893. Two years later he was moved to its newly incorporated Lorain & Cleveland and by 1901 he was acting as the syndicate’s secretary.

By early 1901 the Cleveland–Toledo corridor was beginning to fill up with electric railways, although there were still some significant gaps and those lines which existed had varying physical characteristics. But all the pieces of a through route were in place — in theory at least. Everett-Moore’s own Lorain & Cleveland took the route as far west as Lorain, 27 miles. And at the west end, Michigan interests were just completing the 61-mile-long Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk between the cities in its name.

Filling the gap between Lorain and Norwalk was a company called the Sandusky & Interurban, which had grown out of Sandusky’s original local streetcar system and was then trying to extend itself east along the Lake Erie shore between Sandusky and Lorain. (Legally it was spelled “Sandusky & Inter-Urban,” but neither the company nor anyone else regularly used that spelling.) It had also projected a branch from a point near Ceylon to Norwalk via Berlin Heights. But the S&I consisted more of fond intentions than reality. By 1901 it was bogged down in franchise problems at Huron, Vermilion, and Berlin Heights as well as various other political troubles, and had only been able to complete a ten-mile line between Sandusky and Huron along with some work on the Norwalk branch. One of the S&I’s most intractable problems was bridging the Huron River at Huron on its way east to Lorain. To save its meager capital, it wanted to use the Berlin Street highway bridge, an iron swing structure which the county commissioners felt could not carry interurban cars without being rebuilt.

Finally, there was a second Sandusky streetcar company, the Sandusky, Norwalk & Southern, which also owned a pioneering 1893 interurban route between Sandusky and Norwalk. This offered an alternate link between the S&I and the TF&N — albeit a more roundabout and generally less desirable one.

Despite this disjointed situation, the Everett-Moore group was under pressure to move quickly; there was already competition for their route. The Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk’s Michigan promoters intended either to eventually reach Cleveland themselves or to form part of a connecting route to Cleveland. One plan was to connect at Norwalk with the Cleveland, Elyria & Western, which was slowly building west from Cleveland through Elyria and Oberlin. The CE&W (later part of the Cleveland Southwestern & Columbus system) was the child of the Pomeroy-Mandelbaum syndicate, a rival group of Cleveland interurban financiers headed by A. H. Pomeroy, his son Fred T. Pomeroy, and banker Maurice J. Mandelbaum. It had reached Oberlin in December 1897 but paused there for several years while it financed and built several other branches. In 1901, however, it resumed building toward Norwalk to close the 24-mile gap. Happily for Everett and Moore, a formidable crossing of the Vermilion River valley at Birmingham briefly stymied the extension.

Creating the Lake Shore Electric: 1901

In any event the Everett-Moore group already had moved in. As early as 1898 it apparently was involved in financing the Sandusky & Interurban, and in 1900 it also bought control of the Sandusky, Norwalk & Southern, effectively putting the two Sandusky interurban companies into the same family. With them came Sandusky’s street railway system, which was to prove a future economic albatross but was necessary in order to operate interurbans in the city. Equally necessary but even less remunerative was a short local city operation in Norwalk, required by the franchise inherited by the Sandusky, Norwalk & Southern.

Next Everett and Moore negotiated with the Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk owners, who already were prepared to sell their yet-uncompleted line and had been dickering with the Pomeroy-Mandelbaum interests. Talks began in April 1901 or earlier, and a deal was finally formally acknowledged in July. Everett-Moore now controlled the entire Cleveland–Toledo route, and swiftly moved to consolidate their collection into a single company. Someone, in a happy inspiration, came up with one of the most memorable names in electric traction: Lake Shore Electric Railway. (Pleasant as the name was, however, it strangely gave no clue as to what cities the company served.)

No time was wasted giving it life. On August 29, 1901, the four companies entered into a joint agreement to consolidate as the Lake Shore Electric Railway Company. Its principal offices were to be in Cleveland, Everett-Moore’s base of operations, with an initial organization consisting of nine directors and five corporate officers — president, two vice presidents, a secretary and a treasurer. Barn...