![]() Local Studies

Local Studies![]()

Leah Lowthorp

1Voices on the Ground: Kutiyattam, UNESCO, and the Heritage of Humanity

KUTIYATTAM SANSKRIT THEATER of Kerala state was recognized as India’s first UNESCO Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2001. Looking back a decade later, how has UNESCO recognition impacted both the art and the lives of its artists? Based upon two years of ethnographic research from 2008 to 2010 among Kutiyattam artists in Kerala, India, this essay follows the art’s postrecognition trajectory through its increasing mediatization, institutionalization, and liberalization. Drawing on extended interviews with over fifty Kutiyattam actors, actresses, and drummers, it focuses on reclaiming the voices of affected artists on the ground.

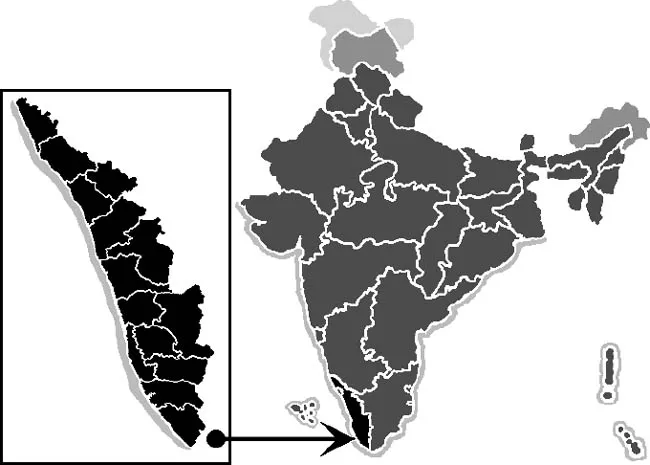

Location: Kerala, India

Kerala is a state largely characterized by exceptionalism. Located on the southwestern coast of the Indian subcontinent along the Arabian Sea (figure 1), the region was known historically for its spice trade with much of the ancient world. At the turn of the twentieth century, Kerala was known for a number of exceptional characteristics—a matrilineal kinship system that gave women comparatively greater autonomy than women in other areas of India; the rule of distance pollution that created the most rigid caste system in India, with lower caste groups not only “untouchable” but “unapproachable” as well; and the relative religious equality, in terms of both tolerance and sheer numbers, between its resident Hindu, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish populations.1 In the course of the twentieth century, Kerala experienced what Robin Jeffrey (1992, 2) has termed “a social collapse more complete than anywhere in India” that entailed the destruction of the matrilineal inheritance system, the spread of formal education and associated rising political activism, and an increasing cash economy that sparked land redistribution legislation by the world’s first (1957) democratically elected Communist government.2

FIGURE 1

Map of Kerala. Public domain image by Saravask, Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:India_map_kerala.png.

The discourse of Kerala’s exceptionalism is most often articulated through what has become known as the Kerala model of development. Formulated in a 1975 report for the United Nations, the model is characterized by Kerala’s low per capita income and high levels of unemployment and poverty coupled with indicators more typical of highly industrialized regions of the developed world, including high levels of literacy and life expectancy and low levels of fertility and infant and maternal mortality (CDS 1975).3 Kerala currently has the highest literacy rate in India (93.91 percent), lowest infant mortality rate (1.4 percent), lowest population growth (4.86 percent), and only natural sex ratio (1.087:1 women-to-men)—factors that have often been attributed to the state’s dominant matrilineal past and political mobilization of social rights led by Kerala’s main Communist party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (Lukose 2009; see also Jeffrey 1992; Franke and Chasin 1992).4 More recently acknowledged for its vital role in the propagation of the Kerala model is the state’s long-standing migration to Gulf countries.5 Resulting remittances flowing into the state coupled with India’s widespread economic liberalization have led to an expansive commodity culture that gives Kerala, despite continued low economic growth, the highest per capita consumer expenditure in India (Lukose 2009; Kannan and Hari 2002). As the Kerala model has become increasingly unsustainable, however, many have come to regard it as a failed project, a utopia-cum-dystopia characterized by “corruption, moral laxity, stagnant economy, widespread unemployment, high suicide rates, alcoholism, indebtedness, increasing violence against women and, more recently, AIDS” (Sreekumar 2007, 43).6

In another manifestation of its discourse of exceptionalism, Kerala has a wider reputation within India as a region preserving “marginal survivals” of an ancient, Sanskritic culture that once spanned the subcontinent.7 Unlike many other regions of India, most of Kerala was never directly ruled by any foreign power, contributing to its status as a “repository of ancient Sanskrit texts” and cultural forms such as Kutiyattam and Vedic chanting (Raja 2001, xii).8 The 1909 “discovery” of the Trivandrum Bhasa plays, which first brought Kutiyattam to wider public attention, exemplified Kerala’s status as a repository in two ways (Unni 2001).9 First, the palm leaf manuscripts represented a rediscovery of the famed second-century CE playwright Bhasa, whose plays were thought to have been lost. Second, the wider discovery of Kutiyattam as a living example of Sanskrit drama in performance challenged the long-held assumption that Sanskrit drama was a purely literary form (Sastri 1915; Keith [1924] 1970). This early framing of Kutiyattam as the only living link with ancient Sanskrit theater practice has persisted through the present-day, resulting in an ongoing temporalization of the art in terms of the past.

ICH Element: Kutiyattam Sanskrit Theater

Kutiyattam is often described as the oldest continuously performed theater in the world, with the earliest records documenting the form dated to the tenth century CE.10 While some have speculated that it began as a secular performance in royal courts, it was definitively incorporated into Kerala’s caste-based temple complex in the thirteenth or fourteenth century, where it remained until 1949 (Narayanan 2006). As a kulathozhil, or hereditary occupation, it was performed in the temple by both men and women of the Chakyar, Nambiar, and Nangiar castes in exchange for land, food, and clothing. Kutiyattam, meaning “combined acting,” embodies a mix of Sanskritic tradition and the indigenous cultural landscape of Kerala. The term encompasses a larger performance complex which includes Kutiyattam, the enactment of Sanskrit drama with multiple actors onstage; Nangiar Koothu, the female acting solo; and Chakyar Koothu, the male verbal solo performance.11 Composed by famous playwrights such as Bhasa, Saktibhadra, and Harsha, the plays staged date from the second to tenth century CE and are performed according to stage manuals passed down as palm leaf manuscripts. The plots generally revolve around the epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, although a few address Buddhist themes. Recognizable by its rich narrative expression through mudra hand gestures, highly emotive facial expressions, stylized movements, and sparse dialogue of chanted Sanskrit, Kutiyattam focuses on the aesthetic elaboration and extension of each moment. Consequently, only one act is ever performed at a time, lasting anywhere from five to forty-one days on the temple stage. On the public stage, where the majority of performances now occur, an act is usually performed on a single night as one edited, three-hour segment.

In the course of the twentieth century, the system that had sustained Kutiyattam as an elite, temple-based occupation for nearly one thousand years crumbled beneath the artists’ feet in a dramatic tide of change that swept over Kerala and the emerging Indian nation. The matrilineal, gurukula-system educated, land-owning Kutiyattam community was unalterably affected by the destruction of royal patronage, the Communist land redistribution legislation depriving artists of their lands, and state legislation officially destroying matrilineal inheritance.12 Many members of Kutiyattam families sought other occupations, thus rejecting the existing agrarian order and becoming “agents of modernity in new forms of employment,” like so many others in Kerala who came to associate their hereditary occupations with an increasingly distant past (Osella and Osella 2006, 571).

A few progressive members of the community fought to adapt both the art and their lives to survive the changing times, giving rise to a discourse of endangerment and samrakshanam (safeguarding) that has persisted in various incarnations through the present day. Actions that were considered unthinkable at the time, such as performing Kutiyattam outside the temple and democratizing its performance community, are now retrospectively narrated as revolutionarily necessary for the survival of the art form. Guru Painkulam Rama Chakyar is credited with taking Kutiyattam out of the temple for the first time in 1949, with teaching the art’s first nonhereditary students in 1965, and with implementing a process of aesthetic reinvention of the art at Kerala Kalamandalam, the state performing arts institution.13 As a result, contemporary Kutiyattam straddles two spheres: the temple and public spheres of performance—the former inhabited by hereditary performers, both professional and nonprofessional, and the latter by professional performers, both hereditary and nonhereditary.14 Often depicted as an ancient art of the Chakyars in Kerala today, Kutiyattam defies such stereotypes through the diversity of its community members, who assert their subjectivity as contemporary artists practicing a contemporary art.

FIGURE 2

From left to right: Kalamandalam Reshmi as Sita, Kalamandalam Sivan Nambudiri as Ravana, and Kalamandalam Krishnakumar as Suthan, 2009. Photograph by author.

Current Status with Regard to UNESCO: India’s First Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity (2001)

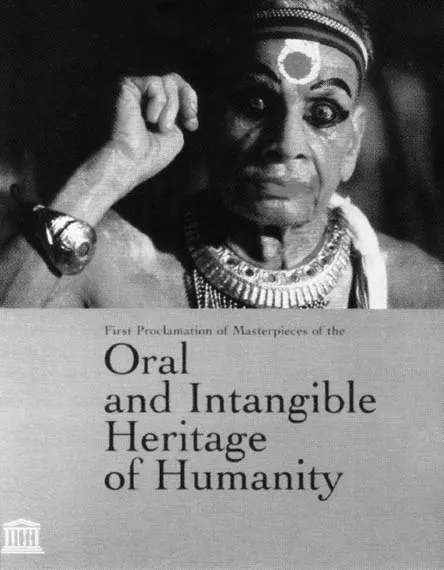

Paris, 1980: The UNESCO Features newsletter reported on a Kutiyattam performance staged in the city as part of the art form’s first international tour, funded in part by UNESCO’s International Fund for the Promotion of Culture (Kinnane 1980).15 Paris, 1999: While on tour to Paris again, a UNESCO representative came to the performance and encouraged the Kutiyattam troupe members to apply for a new program that UNESCO was launching.16 Granted UNESCO funds for the application, it was through the effort of the troupe’s leader and a few other key individuals, such as internationally renowned film director Adoor Gopalakrishnan, that Kutiyattam’s application was submitted to UNESCO by the Indian government as its only candidate that first year.17 The art’s national and international connections thus laid the foundation for its international recognition. When the first Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity was subsequently announced in 2001, Kutiyattam became India’s first expressive tradition to be so recognized by UNESCO, although not without controversy (figure 3).18

While the Indian Ministry of Culture began budgeting a small amount for the “preservation and promotion of intangible heritage of humanity” in 2003, Kutiyattam’s action plan began to be implemented in 2004 primarily through a UNESCO/Japan-Funds-in-Trust project, which issued 150,000 US dollars to six institutions over a period of three years (Government of India 2003–4, 182; UNESCO 2007).19 Under the direct oversight of the UNESCO New Delhi regional office, the funds were used to support meetings of a Kutiyattam network, the revival of plays, publications, student training, public awareness-raising workshops and performances, academic seminars, the production of ten documentaries, and a workshop on basic conservation techniques for palm leaf manuscripts. In 2006, a special fifty-million rupee provision was made in the National Budget for India’s three UNESCO Masterpieces—Kutiyattam (2001), Vedic Chanting (2003), and Ramlila (2005).20 This sparked a fight between two major national institutions for control of the project, the Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA) and the Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts (IGNCA). The SNA eventually emerged victorious based on its long-standing financial support of Kutiyattam, and in 2007 it founded a national center, Kutiyattam Kendra, in Kerala’s capital city of Trivandrum.21

FIGURE 3

Guru Ammannur Madhava Chakyar on the cover of UNESCO’s First Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, 2001. UNESCO.

The Sangeet Natak Akademi, India’s national academy for dance, drama, and music, began translating Kutiyattam into national heritage early on, clearly valuing the art for its “pastness” through its widespread characterization as “the only surviving link to the ancient Sanskrit theater” (SNA 1995; see also Lowthorp 2013b). This is part of a longer process of Indian nation building that, as Vasudha Dalmia (1997) has argued, appropriated Orientalist discourse through the “nationalization” of Hindu traditions viewed as legitimized in ancient, Sanskrit texts. Thus viewing Kutiyattam as a marginal survival of an ancient Vedic (i.e., Hindu) age, the SNA began showcasing and documenting the art in the 1960s and incorporated it into a funding scheme targeting endangered art forms in the 1970s. This eventually culminated in a “total care plan” for the preservation of Kutiyattam which provided low, steady levels of funding starting in 1991 (SNA 1991–92).22 With the 2007 opening of the Kutiyattam Kendra, funding for Kutiyattam was significantly increased and the art became included in a small, elite group of the SNA’s permanently funded institutions.23 Remaining under the purview of the SNA, which continues to characterize the art as both endangered and as India’s only living link to ancient Sanskrit theater, Kutiyattam’s post-UNESCO project implementation has constituted a continuity of state policy, both in discourse and practice.

Kutiyattam Kendra ushered in a number of initiatives. Prioritizing Kutiyattam’s transmission, it began distributing augmented student and teacher stipends to three existing and four new institutions.24 It funded ...