![]()

1

CONTESTING THE STATE BY BYPASSING IT

CONTEMPORARY “FUNDAMENTALIST” MOVEMENTS1—or as we prefer to call them, religiously orthodox movements—have been the subject of much scholarship, media coverage, and political punditry. Missing in nearly all accounts of the nature, strategies, and impact of such movements is an understanding of their underlying communitarian logic, including a compassionate side that leads to much of their institution-building, their outreach to those in need, their success in recruitment, and their popular support. Even when this caring side of religiously orthodox movements is recognized, it is often misunderstood as mere charity.2 Unrecognized is the fact that, for many of the most prominent orthodox movements, this institutional outreach—such as building clinics and hospitals, establishing factories that provide jobs and pay higher-than-prevailing wages, initiating literacy campaigns, offering hospices for the dying, providing aid to the needy, and building affordable housing—is spread throughout the country and linked with schools, worship centers, and businesses into a dense network with the aim of permeating civil society with the movement’s own brand of faith. Yet to overlook or misunderstand this strategy is to seriously underestimate the reach of religiously orthodox movements and their success in infusing societies and states with religion.

While religiously orthodox movements are often portrayed as irrational or reactionary, we show in this chapter that they are motivated by a logic of communitarianism that is neither consistently right wing nor left wing. This communitarian logic leads them to establish places of worship, schools, social welfare agencies, and businesses that ultimately grow into extensive networks of alternative institutions and, in some cases, a parallel society or state within a state. This nonconfrontational, institution-building strategy can be an end in itself, since it can result in the permeation of society with religious sensibilities, religiously based standards on family and sexuality, and faith-based outreach to those in need. Or if state takeover is the goal, it can help the movement build a strong base of popular support that can be translated into electoral victories in the formal political arena.

RELIGIOUS ORTHODOXY AS COMMUNITARIAN

To understand the logic underlying religiously orthodox movements, their political agendas, and their strategies, we begin with a distinction between two “fundamentally different conceptions of moral authority,” first made by sociologist James Davison Hunter in his 1991 book, Culture Wars. The religiously orthodox vision views a deity (that is, Allah, Yahweh, God) as the ultimate judge of good and evil; regards sacred texts (and clerical teachings derived from these) as divinely revealed, without error, and timeless; and sees this supreme being as watching over, affecting, and judging people’s daily lives. In contrast, the modernist3 vision views individuals as having the freedom to make moral decisions in the context of their times; sees religious texts and teachings as human creations that should be considered in cultural and historical context along with other moral precepts; and regards individuals as responsible for themselves and as largely independent in making their lives and fates.4 Modernists need not be atheists or agnostics; in the United States, for example, most modernists believe in God.5

In a series of conceptual and empirical articles,6 we have drawn out the theological and political implications of Hunter’s ideal–typical visions of moral authority and have recognized that actual individuals, religious groups, and movements exist along an orthodox to modernist continuum, not necessarily at the polar extremes or encompassing fully every aspect of one or the other ideal type of moral cosmology. Our theoretical model, moral cosmology theory,7 shows how the orthodox and modernist moral cosmologies differ theologically and how these differences affect the political attitudes and behavior of those who hold these moral cosmologies. Our model applies only to the Abrahamic faith traditions, which include Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—all of which regard Abraham as a prophetic figure. Another common expression for these traditions is “religions of the Book,” and we use this interchangeably with Abrahamic religions throughout this book. The key characteristic of the Abrahamic faiths, which is lacking in the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, is having a sacred book that is seen as revealing divine, eternal truths and laws. The existence of the sacred book gives rise to the orthodox, who take the text to be literally true for all times, places, and peoples, and to (at the opposite pole) modernists, who regard the text as requiring human interpretation, adjustment to contemporary circumstances, and integration with other moral and juridical principles in formulating law for societies today. Few Hindus or Buddhists take any of the many sacred books of their faith literally, word for word, and hence the orthodoxy/modernism distinction does not apply well to Hinduism and Buddhism.8

Our argument is that the religiously orthodox cosmology is theologically communitarian in that it regards individuals as subsumed by a larger community, all members of which are subject to the laws and greater plan of a deity. In the orthodox cosmology, timeless religious truths, standards, and laws are seen as having been laid down once and for all in a sacred book or in teachings derived from this by a supreme being—laws that the community must uphold and that everyone is obliged to obey. Thus there is a strict or authoritarian side to the theology underlying orthodoxy.

At the same time, theological communitarianism entails the belief that the individual’s faith can find its full realization and expression only in the context of a larger community of believers. Individuals in the faith have an obligation both to seek out others who have arrived at the same understanding and to share this with those who have not yet come to the faith or who have lost it. This often entails the sense among the orthodox that they are part of a “sacred community.” Gabriel Almond, R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan note that among North American fundamentalists, referring to themselves as “‘yoked together’ [is] the ultimate praise for insiders, for the saved.”9 There is often the notion of individuals as being spiritually equal or potentially equal before Allah, as being “children of Yahweh,” or as part of a larger “family of God.” The theological communitarianism of the orthodox thus entails elements of sharing, caring, mutuality, and responsibility for others.

Communitarianism, like the notion of “community” on which it is based, has elements of both inclusivity and exclusivity. It involves drawing the line between those who have come to the correct understanding of the faith and those who have not—between those who are “real” or “authentic” Christians, Jews, or Muslims and those who are not. Yet it also includes the potential for everyone to take up or return to the “true” faith, and hence the obligation to proselytize outside the community of true believers.

We argue that the two sides of the theological communitarianism of the orthodox cosmology—the strict and caring sides—have important implications for the politics of those who hold this moral understanding. The strict side inclines the orthodox to an authoritarian strand of cultural communitarianism, in which the community must enforce what it sees as divinely mandated standards on sexuality, gender, reproduction, and family life, which in practice has often meant forbidding abortion, homosexuality, or sex outside marriage; making divorce difficult or impossible to obtain; and mandating specific and different roles for men and women, husbands and wives.10 At the same time, the compassionate side of theological communitarianism inclines the orthodox to economic communitarianism, whereby it is the community’s or state’s responsibility to share with or provide for those in need, reduce the gap between rich and poor, and intervene in the economy so that the needs of all community members are met. The communitarianism of orthodoxy thus entails “watching over” community members, giving it politically both a strict side and a caring11 one, and inclining its adherents toward cultural authoritarianism and economic egalitarianism.12

Orthodoxy, as we (and Hunter) conceive it, refers not to “doctrinal” orthodoxy or belief in the specific tenets of a faith tradition (e.g., the divinity of Christ, the obligation to pay zakat or mandatory alms) but to a broad theological orientation toward the locus of moral authority with which the orthodox of all the Abrahamic faith traditions would agree. In other words, orthodox Christians, Jews (with a small “o” to distinguish their cosmology from formal membership in the Orthodox branch of Judaism), and Muslims adhere to some religious tenets that are different, but they share the broad worldview that the locus of moral authority is a supreme deity and that legal codes should reflect absolute and timeless divine law.

Neither orthodoxy nor modernism should be equated with any specific faith tradition or denomination. Among individuals who are Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, or Protestant, we have found in our prior quantitative research that there are those who are orthodox in their cosmologies, those who are modernist, and those who combine elements of orthodoxy and modernism. This is even true in the United States among categories of Protestants such as evangelical, mainline, or black Protestants. Within each of these types of Protestants, we have found a range of moral cosmologies, although of course the range in some cases may tend to lean toward either the orthodox or the modernist pole. Moreover, in analyses explaining Americans’ positions on cultural and economic issues, we have found that moral cosmology (ranging from orthodoxy to modernism) usually has independent effects from denomination (Catholic, Jewish, evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant, black Protestant, other, none).13

In contrast to the orthodox, theological modernists are theologically individualistic in that they see individuals, and not a deity, as largely responsible for their own moral decisions and fates. Reflecting Enlightenment ideals, the modernist cosmology combines support for individual choice and freedom with the expectation of individual responsibility,14 inclining its adherents to cultural individualism or libertarianism, whereby, for example, the resolution of an unwanted pregnancy is seen as a woman’s private decision, individual choice in sexual expression is allowed, and husbands and wives should decide for themselves how to divide their labor or structure their partnership. The theological individualism of modernists also inclines them to laissez faire economic individualism and hence less willingness to use community or state resources to help those in need. Since modernists are inclined to hold individuals responsible for what happens to them, the poor and jobless are considered to be largely responsible for their own economic misfortune. Thus, for modernists, the tendency is to see greater effort and initiative by the poor themselves as the solution to poverty and inequality rather than collective efforts by the community or state to, for example, improve their lot, equalize incomes, or redistribute economic resources by nationalizing businesses.

RIGHT OR LEFT?

Our argument in moral cosmology theory about the political leanings of the orthodox and modernists goes against the common wisdom that the orthodox are to the political right, while modernists are to the left. The traditional way of representing political space as a single dimension, running from right to left, is shown in figure 1.1, where we have also located the religiously orthodox and modernists according to conventional thought—a view we reject.

Figure 1.1. One-dimensional political continuum, showing conventional view of the locations of the religiously orthodox and modernists.

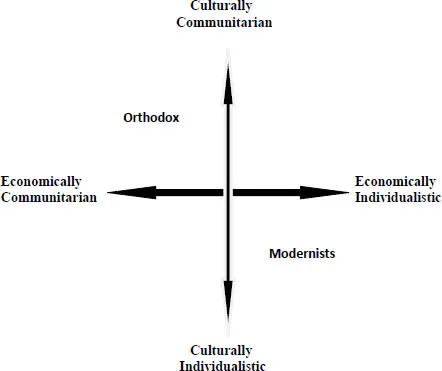

In our earlier quantitative research analyzing the positions of the orthodox and modernists around the world,15 we found that political space is better represented as two-dimensional, with one dimension representing cultural issues and running from culturally communitarian to culturally individualistic and another dimension representing economic issues and running from economically communitarian to economically individualistic (see figure 1.2).

That individuals and groups may position themselves differently on cultural and economic issues has been recognized for some time. U.S. sociologist and political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset, writing in 1981, distinguished between cultural conservatism and economic conservatism, the former referring to efforts to restrict freedoms with respect to sexuality, reproduction, marriage, and family and the latter to efforts to support laissez faire economic principles.16 Reconceptualizing political space to have a cultural dimension and an economic dimension allows us to locate the religiously orthodox and modernists as shown in figure 1.2. Situating these moral cosmologies in two-dimensional political space shows that the religiously orthodox, relative to modernists, tend to be more communitarian on both the cultural and economic dimensions. Because the religiously orthodox are, in conventional left–right terms, more to the right of modernists on cultural issues but more to the left of modernists on economic ones, the complexity and consistency (in terms of communitarianism) of their position cannot be captured by the conventional, one-dimensional, left–right continuum (figure 1.1) and may lead to their being viewed as irrational or, if the economic dimension—their caring side—is ignored, as consistently right wing.

In the United States, as we show in figure 1.3, neither the religiously orthodox nor modernists are in the same political quadrants as the two major political parties, the Republicans and the Democrats. To win the votes of many of the religiously orthodox, each of these parties must emphasize the issue positions that it shares in common with them and deemphasize the positions on which it differs from them. Thus, in attracting votes of the orthodox, Republicans must emphasize their positions on cultural issues, such as legislating against abortion and same-sex marriage, while deemphasizing their positions on economic issues, such as cutting welfare spending, repealing health care legislation that covers all Americans, and maintaining tax cuts for the wealthy. Democrats must take the opposite strategy in winning over the orthodox: emphasize their positions on economic issues but deemphasize their positions on cultural issues.

Figure 1.2. Two-dimensional political space, showing the locations of the religiously orthodox and modernists according to moral cosmology theory.

While these are the dominant tendencies of the orthodox relative to modernists, there are exceptions to these inclinations. Some modernists, such as secular democratic socialists, hold communitarian economic beliefs. And some religiously orthodox people, such as televangelist Pat Robertson in the United States, hold laissez faire individualistic beliefs on economic matters. Nonetheless, quantitative analyses of nationally representative surveys by ourselves and other scholars on the effect of moral cosmologies (orthodoxy to modernism) on cultural attitudes (abortion, homosexuality, birth control, divorce, appropriate roles for women and men) and economic attitudes (poverty, inequality, joblessness) have found in twenty countries that the religiously orthodox are more communitarian than modernists on both economic and cultural issues. This pattern has been found in countries that are predominantly Protestant (Norway, the United States), mixed Protestant and Catholic (West Germany), Catholic (Austria, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Portugal), Eastern Orthodox (Bulgaria, Romania), Jewish (Israel), and Muslim (Algeria, Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Jordan, Ka...