![]()

PART I

PHOSPHATE PASTS

There can be no civilization without population,

no population without food,

and no food without phosphate.

—Albert Ellis, Phosphates: Why, How and Where?

![]()

1 The Little Rock That Feeds

Let’s-All-Be-Thankful Island

On September 20, 1919, Thomas J. McMahon, one of the most prolific journalists and photographers of the South Pacific of his time, published a story in an Australian magazine called the Penny Pictorial. It was replete with the usual Pacific imagery and language—paradise, romance, natives, South Seas, balmy breezes, and so forth—with one notable exception. The title of the piece proclaimed: “Let’s-all-be-thankful Island. A Little Spot in the South Pacific That Multiplies the World’s Food.” McMahon had just visited Ocean Island, indeed one of the tiniest inhabited dots in the Pacific, and produced extraordinary images of productive, orderly, brown laborers and impeccably clad white folk—men, women, and children—against a backdrop of less than tropical rock pinnacles and mining fields. Less than a year later the governments of Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom bought out the Pacific Phosphate Company and created the British Phosphate Commissioners (BPC), tasked with mining Nauru and Ocean Island in the Pacific and, later, Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean. Across the seas, the Cherifian Phosphates Board (Office Chérifian des Phosphate), today the world’s major phosphate supplier, was established in Morocco that same year.

In 1900, two of the world’s highest-grade sources of phosphate rock were identified on Nauru and the island of Banaba in what is now the Republic of Kiribati in the central Pacific. The history of Nauru has been told in a variety of forms, but that of the smallest of the phosphate islands is much less well known.1 In this book I present a series of stories about Banaba from 1900 through the present, with a focus on the political and social impacts of phosphate mining and the displacement of both the land and the indigenous Banabans. While deeply concerned with the ethical and moral implications of unbridled resource extraction for indigenous peoples and global consumers, I also reflect on the process of tracking this multisited, multiscalar, and multivocal history and the varying ideological and ontological positions taken by what some might call the major and minor agents of change. Of central concern are the relations between people and the land, people’s relations to each other, and the relations between the past and the present. The island of Banaba is an entry point and the key motif linking these stories; we spiral through time, experiencing the island’s material development, decimation, and global consumption as well as the changing sociopolitical landscapes created across the mining enterprise. From the past we can see the future, and vice versa.

“Babes in the Pinnacles” by Thomas J. McMahon. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia

Banaba, mapped by Europeans in the early nineteenth century as “Ocean Island,” is a two-and-a-half-square-mile (six-and-a-half-square kilometer) island in the central Pacific.2 Now in a state of relative obscurity, the island was the intense focus of British imperial agricultural desires for most of the twentieth century. Phosphate rock is the essential ingredient in phosphate fertilizers, which are crucial for the maintenance and expansion of global agriculture and therefore key to global food security. Both of these island landscapes were essentially eaten away by mining, which devastated both the land and spirit of their respective peoples while supporting thousands of Company3 employees and families and fueling agriculture in the British Antipodes for much of the twentieth century.

Nauru, once known as Pleasant Island and a former colony of Germany, eventually acquired international rights to self-determination and independence after World War II, initially as an Australian Trust Territory of the United Nations. These rights did not extend to Banaba, however, which was colonized by Britain. Nauru gained independence in 1968, and from 1970 the Nauruan government itself ran the mining industry, becoming temporarily one of the wealthiest countries in terms of income per capita. In the 1990s the Commission of Inquiry organized by the Nauruan government focused on the requirements for the environmental rehabilitation of worked-out phosphate lands. This resulted in the Nauru and Australian governments signing the Compact of Settlement, which provided for remining by Australian companies followed by rehabilitation of the mined-out lands.4

Since independence, however, a string of bad investments and dealings left Nauru in debt, reliant on Australian aid, and with a 90 percent unemployment rate and a range of challenging health issues.5 It is currently the smallest republic in the world with a land mass of eight square miles (twenty-one square kilometers) and approximately 9,000 people. While their culture has been heavily influenced by mining and colonialism, and Nauru is now a major and controversial center for the processing of asylum seekers who want entry into Australia, Nauruans are active in revitalizing their culture through fishing, sport, music, and dance.

There is a population of approximately 400 Banabans and I-Kiribati on Banaba today, living there as caretakers while the majority of Banabans live on Rabi in Fiji. On Banaba, where fishing grounds, homes, villages, and ritual and burial sites once existed, there are now stark limestone pinnacles, decaying processing plants, rusted storage bins, algae-congested water tanks, and a massive maritime cantilever with its giant arm crippled and submerged. The island is administered by the Rabi Council of Leaders and the Kiribati government.

Two other Pacific islands, Angaur in the Caroline Islands and Makatea in French Polynesia, are much smaller but still have been critical sources of phosphate. They are both sparsely populated but still of significance to their indigenous peoples. The same Company that mined Banaba and Nauru partnered with a Tahitian-based syndicate to mine Makatea. While the Pacific phosphate deposits constituted only about 8 percent of the world’s annual output at their peak, they were for decades essential regional sources for Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, which were without domestic supplies and would incur great freight costs to import phosphate from the United States, Morocco, or South Africa.6

During almost a century of mining, shipping, and manufacturing, the rock of both Nauru and Banaba was scattered across countless fields in and beyond the British Pacific. In this period the United Kingdom, France, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand all had colonies in the Pacific islands, some as a result of the post–World War I League of Nations Mandate, and others as a result of prewar imperial claims and divisions that initially included German and Japanese territories. The Pacific was yet another theater for the expression of British, American, European, Japanese, and later Indonesian martial power, as well as a strategic opportunity for securing natural resources and expanding metropolitan business interests. The development of mines and plantations was also a necessity on some islands for funding the administration of the colonies, and Banaba was no exception. Phosphate mining, even on an island as tiny as Banaba, made British, Australian, and New Zealand investors very wealthy; supplied farmers with cheap fertilizer while stimulating various chains of commodity production, distribution, and consumption; and funded the administration of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony through taxes.

While expanding populations were enjoying the agricultural benefits of intensive fertilizer application and the phosphate-hungry high-yielding crops of what USAID director William Gaud coined the “Green Revolution” in 1968, there was and continues to be little public education or awareness about humanity’s reliance on phosphorus. What the Green Revolution failed to acknowledge was the reliance not just on land for agricultural development and the expansion of mono-cropping, but on resources that would fuel the entire chain of agricultural outputs, most significantly fertilizer. Knowledge of certain key ingredients, such as phosphate, was specialized and rarely successfully popularized, in spite of the attempts of various travel writers and journalists.

The epigraph for this part of the book was originally by Clemson University founder Thomas Clemson. His statement on the crucial link between food and phosphate was quoted in a speech by Pacific “phosphateer” Sir Albert Ellis to the Auckland Rotary Club in New Zealand in 1942: “Phosphates: Why, How and Where? . . . Why Needed? How Used? and Where Found?”7 Media coverage of phosphorus and phosphate issues more than seventy years later still sustains this curious tone of excited discovery, as if telling the story for the first time to an unknowing audience. For his lay listeners, Ellis adjusted Clemson’s original line, which contained the more accurate technical term “phosphoric acid,” the industrial shorthand P2O5 for water-soluble phosphate, rather than “phosphate.”

For the layperson, there is often confusion about the differences between guano and rock phosphate. Guano, from the Quechua word wanu, is the excrement of seabirds, bats, and seals. There were major guano sources across the Pacific and Caribbean with the largest deposit in Peru, in some cases mined by slave labor from the Pacific.8 Rock phosphate is the result of millions of years of sedimentation while guano, which also provides nitrogen, is younger in formation. They both yield phosphoric acid with the latter an ostensibly more “natural” fertilizer. Organic farmers, for example, prefer to use guano, and journalists and travel writers thrive on the vivid metaphors and images conjured up by humans’ obsession with bird and bat shit.9

Maslyn Williams, Barrie Macdonald, Christopher Weeramantry, and Nancy Viviani have all produced important scholarship on the history of mining on Banaba and Nauru.10 Williams and Macdonald’s celebratory account of the BPC is a careful distillation of a large collection of archival records organized into an evocative and entertaining narrative that gives a dense and temporally linear view of the economic and political stakes of this industry for the three stakeholder nations: Great Britain, New Zealand, and Australia. Much less attention is given to any Pacific Islander actors, indigenous or otherwise. Their voices and experiences are muted in these political histories.

Land: Sedimentation, Traveling Rocks, and Fragments

Throughout this book I bring indigenous Banaban concepts and experiences into dialogue with competing regimes of value and the industrial processes applied to Banaban land by powerful actors and agencies from across the former British Empire. I track the phosphate, stories of life on the island, the Banabans, and various events in which they were entangled over several landscapes. Each story is an interlocking piece of the puzzle, partially sedimented, layered, and overlapping, but ultimately fragmented and diffracted in parallel with the now-dispersed phosphate landscape.

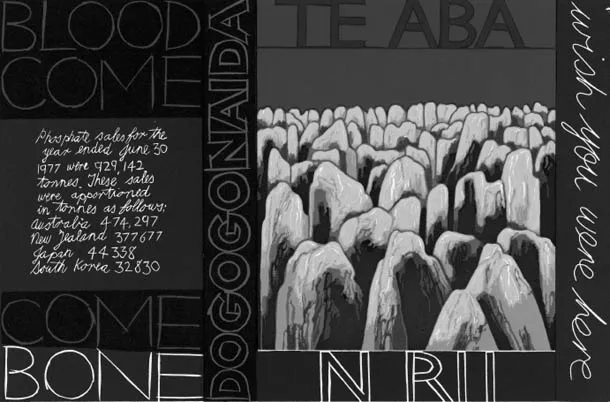

In most Pacific languages there are central concepts linking the people and the land metonymically, ontologically, and spiritually: vanua in Fijian, aina in Hawaiian, and whenua in Māori, for example. Te aba, kainga, and te rii in Gilbertese (the Kiribati language) refer, respectively, to the land and the people, home or hamlet, and bones. All have linguistic, human, and material forms that can be interchangeable, substituted, or used to indicate linked parts of a whole, which is the land and people together. “Te aba” thus means both the land and the people simultaneously; there is a critical ontological unity. When speaking of land, one does not say au aba, “my land,” but abau, “me-land.” Te aba is thus an integrated epistemological and ontological complex linking people in deep corporeal and psychic ways to each other, to their ancestors, to their history, and to their physical environment. Sigrah and King speak of “te rii ni Banaba,” the backbone of Banaba, as the spiritual wealth and well-being of a person involving three pieces of knowledge: knowledge of one’s genealogy, knowledge of one’s customary rights, and knowledge of one’s land boundaries.11 Relations to land are extremely serious. Though it might increasingly be used as such, land is not merely for exploitation or profit. Land is the very basis for relationality and for knowing and being.12 These various facets of land and the manner in which they relate to the area’s mining history are captured lucidly in New Zealand artist Robin White’s Postcard from Pleasant Island III. She manages to evoke the land as body, blood, and rock, the mined landscape resembling a gravesite that has become te aba n rii, the land of bones.

“Postcards from Pleasant Island III: Te Aba n Rii,” by Robin White. Used with permission of the artist and courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia.

Banaba was viewed as the buto, the navel or center of the world, by Banabans, much as other islands, including Nauru and Rapa Nui, were viewed by their indigenous inhabitants.13 While Banaba was settled by at least three waves of migration beginning over two thousand years ago, emplaced identities were forged and consolidated over the centuries so that personhood was shaped within a network of both kinship-based and environmental relations and connections. Most significant, on Banaba, in contrast with most Pacific societies, including in the Gilbert Islands, land was not held communally.14 Each individual, male and female, adult and child, had their own carefully demarcated plots that they could keep, exchange, or dispose of at will.15 Land was thus the ground for individual agency and efficacy within a communal system of social organization. The subsequent ...