![]()

1

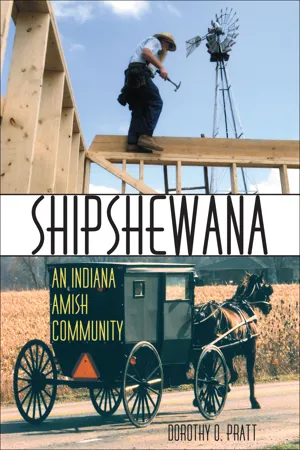

The LaGrange County Settlement

When the Amish arrived in northern Indiana in 1841, they were not so very different from their neighbors. Everyone traveled by foot, by horse, by carriage. No one had electricity. Few received education beyond the eighth grade. Most dressed plainly, although not all by choice. Many groups deviated from the mainstream of religious theology; within LaGrange County itself were Millerites, Mormons, and even a Phalanx. In addition, a surprising number of people in the adjoining counties spoke German, including the Mennonites and many recent German immigrants of different denominations.1 By 1917, however, the Amish were firmly entrenched in Newbury Township in LaGrange County and were becoming noticeably different from their neighbors.

During the years of relative geographical isolation (1841–1917), the Amish made a concerted effort not to change by clearly drawing their cultural boundaries. Within these boundaries, they created integrated economic and social structures that tied the sect together through a “primal network of relationships.”2 This chapter concentrates on the integral structures that allowed the Amish to be dependent on each other and independent from those around them. Chapter 2 addresses boundary formation and construction during these same years as the Amish defined who could be included in membership, who excluded, and how to control the influence of outsiders.

The Amish were able to remain in LaGrange as a distinct ethnic group for two reasons. The first was their superlative skill as farmers; this competence created economic stability for growth and earned grudging respect from their neighbors. A stable economy is central to the survival of any group; from a practical standpoint, little energy can be devoted to the development of a culture if one’s energies must be devoted exclusively to sustaining life. Although the economic circumstance of the Amish community in LaGrange was not luxurious by contemporary standards, for the most part it was comfortable. Such economic stability allowed the Amish to nourish order, one of the most fundamental tenets of their culture. This order, or social stability, was the second reason the Amish endured.

Not by chance was the Amish tradition of Christian community life called the Ordnung. As an order of behavior, it created a set of communal expectations and a sense of belonging. During the years of relative isolation, the Amish forged a carefully fabricated, orderly community life. The family was the center of the order, and the life the Amish established in this rural enclave precisely defined how the family lived, worked, and behaved. This story, however, is mostly unexplored.3

Settlement

Histories of Indiana largely ignore the northern areas before the Civil War.4 Indiana became a state in 1816, and by the 1840s it already had a history, albeit a short one, and a tradition of governance. In fact, the state was already past the frontier stage, losing more people than it was gaining.5 In the early 1800s the land in the northern part of the state was slow to be settled for two reasons. The first was access. Travelers could reach Illinois and Iowa from the Mississippi River or through the Great Lakes. In contrast, newcomers to northern Indiana came by foot or by slow, plodding covered wagon, since most roads tended to bypass the area: the National Road went through Indianapolis to the south, and the old Indian trail from Chicago to Detroit went north of Indiana through Michigan. Much of the northeastern land was swampy and known for its noxious fumes.6

The second reason for the slow settlement of the northern counties was that this was still Indian country. The sparse settlements in the northern counties were there illegally until the last of the Potowatomis were removed in 1840.7 One of the natural lakes in the county bore the name Shipshewana, in honor of the last Potowatomi “chief” in the area; according to legend, he returned there in his final days and was buried on the lakeshore.8

Fortunately, a contemporaneous account of the settlement of this area gives remarkable insight into the frontier process. In 1907 Hansi Borntrager, an elderly Amish man, wrote a brief history of the LaGrange settlement to help his family remember their heritage.9 Since Borntrager was only a small child when his family came to Indiana in 1841, he invited comments from many of his friends and fellow pioneers to ensure accuracy. In addition, much of Borntrager’s account can be verified through other sources.10

According to Borntrager, around 1840 four Amish men living in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, began to search for new land for their community.11 After traveling down the Ohio River, then up the Mississippi, they found acceptable land in Iowa. For their return journey, however, they chose a different route: through Chicago, then along the St. Joseph River and into northern Indiana. Once they left the river, they traveled by foot into what is now Goshen, Indiana. Borntrager does not offer an explanation for this circuitous route, but possibly the men were attracted by other nonresistant settlers already living in the area. Whatever the reason, the men found the Indiana land even more attractive than that in Iowa. As a result, in 1841 four families moved to Indiana from Pennsylvania, taking four weeks for the trip.12

At first the settlers camped on the Elkhart Prairie near the present-day town of Goshen. To their dismay, they discovered that the choice prairie land was too expensive for their limited means. Just to the east, in Newbury Township in LaGrange County, they found less expensive land that came with a different cost: felling the forests. In the 1840s clearing land of trees could take two or more years; if one had many forested acres as well as marshland, generations might pass before everything was cleared. In short, as one student of the Amish has noted, “Buying a quarter section of land—more or less—and clearing it for farming was not for the faint of heart.”13 During the following summer other Amish families arrived in Indiana, some settling in Newbury Township near the present-day town of Shipshewana and some in Clinton Township in adjacent Elkhart County. In the succeeding years the Amish community grew rapidly by natural increase and immigration.14

In the first year the settlers burned the forest floor, planted small plots, and felled trees to make simple log homes. These rudimentary cabins, constructed from round logs and heavy chinking, had beaten dirt floors, stick chimneys, and greased paper for windowpanes. At the start, a quilt tacked onto the lintel substituted for a door; later a simple entry with a string latch was added. Eventually clapboards could overlay the house, stones would be laid for the chimneys, and floorboards were added. A small cellar under the new flooring sufficed to store potatoes and other root vegetables. The furniture was equally sparse.15

During the early years of isolation, people survived on what they grew or could forage in the wild. Since fencing would not become common in the township until well into the twentieth century, livestock ran at large, identified only by a mark that was registered with the county recorder.16 Life was not dull, even in this agricultural backwater of the nation. For example, in the next county to the south, a group of bandits operated in a relatively unpopulated area and made forays into Elkhart, LaGrange, and other counties to rob and murder. Often these raids occurred while people were away from their homes at church. A group of Regulators composed of men from the neighboring counties finally apprehended the bandits in 1858.17

This frontier stage, however, was short-lived, with change coming faster to northern Indiana than to the southern counties. By 1846 a noticeable exodus of people heading to Oregon outnumbered the fresh immigrants to the county.18 Yet for those who stayed, cleared trees, drained marshland, and improved roads, a certain amount of prosperity appeared, even among the Amish. Records indicate a new sawmill, a school, and fledgling county government.19 Amish even served on the school board and in other county offices.20

In short, between 1841 and 1917 the Amish settled comfortably in LaGrange, earning a reputation as good farmers in this agricultural county. In 1874, almost midway through the period, the Illustrated Historical Atlas of LaGrange County described them as a “peculiar class of people . . . found mostly in Newbury and Eden.” The rest of the paragraph reflects both respect and some resentment: “They believe, however, in gathering together all of Uncle Sam’s greenbacks which they can reach, and understand thoroughly how to make money.” In addition, the author added, “They are good farmers generally, and own some of the best lands in the county.” Under the heading for “Eden Township,” the author refers again to the Amish as “generally good farmers, [who] have the faculty, superlatively developed, of accumulating ‘filthy lucre’ and real estate.”21

These comments about the Amish raise more questions than they answer. Were the Amish, in fact, good farmers?22 How far did they participate in the market economy? Were they as miserly as the stories suggest? How economically secure were they as a group in Newbury Township? To respond to those questions and to evaluate the economic stability of the Amish during this period, one must analyze their practices as farmers, examine their crop choices, and evaluate the Amish reaction as the state shifted from agricultural to industrial wealth.

Censuses

Unfortunately, the data for farming practices in the mid-nineteenth century are severely limited. Manuscripts for the Agricultural Census are available only through 1880. In 1890 a fire destroyed national records, and the Bureau of the Census chose not to retain agricultural manuscripts after that year, much to the irritation of historians. Even within the surviving manuscripts, verification as to who was Amish or Mennonite becomes increasingly difficult.23 For the censuses of 1860 and 1870 it is fairly easy to determine who was Amish or Mennonite by surname identification; during these years agricultural practices also tended to reflect ethnic tradition. After 1870, however, surnames are not reliable, because following the Great Schism of 1857 families split; in-migration of Dunkers and other types of Mennonites introduced new and sometimes similar surnames; and some second-generation communicants converted to noncognizant denominations, such as Methodist or Presbyterian. It is possible to trace some Amish families from present membership, but this is a particularly difficult exercise for the latter part of the nineteenth century because of the extensive migrational shifts of Amish families.24

In spite of these problems of ethnic identification, some conclusions about Amish farmers are possible. The Amish shared with all farmers the complications endemic to the area. Everyone in Newbury Township had to contend with marshlands and the need for drainage. Although the county is riddled with small creeks and seventy-one natural lakes, they were insufficient to provide natural drainage for large marshes, wetlands, and peat bogs.25 During the nineteenth century, LaGrange County farmers made a concerted effort to drain these lands.26 The local newspaper supported these efforts, adding exhortations about keeping hoes sharp and preserving meadows and marshland because of the huckleberry and blackberry crops that came from them.27 To provide drainage, farmers either bought or produced tile, laid it in the fields, and projected the runoff into local streams.28 If streams were unavailable, farmers had to agree about ditches or passage to local creeks, streams, and rivers. How this was accomplished in Indiana and particularly LaGrange County is frustratingly undocumented. One possibility ...