- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A survey of British women's writings of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the revolutionary New Woman they promoted.

British women writers were enormously influential in the creation of public opinion and political ideology during the years from 1780 to 1830. Anne Mellor demonstrates the many ways in which they attempted to shape British public policy and cultural behavior in the areas of religious and governmental reform, education, philanthropy, and patterns of consumption. She argues that the theoretical paradigm of the "doctrine of the separate spheres" may no longer be valid. According to this view, British society was divided into distinctly differentiated and gendered spheres of public versus private activities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,

Surveying all the genres of literature?drama, poetry, fiction, non-fiction prose, and literary criticism?Mellor shows how women writers promoted a new concept of the ideal woman as rationally educated, sexually self-disciplined, and above all, virtuous. This New Woman, these writers said, was better suited to govern the nation than were its current fiscally irresponsible, lecherous, and corruptible male rulers.

Beginning with Hannah More, Mellor argues that women writers too often dismissed as conservative or retrogressive instead promoted a revolution in cultural mores or manners. She discusses writers as diverse as Elizabeth Inchbald, Hannah Cowley, and Joanna Baillie; as Charlotte Smith, Anna Barbauld, and Lucy Aikin; as Mary Wollstonecraft, Charlotte Reeve, and Anna Seward; and concludes with extended analyses of Charlotte Smith's Desmond and Jane Austen's Persuasion. She thus documents women writers' full participation in that very discursive public sphere which Habermas so famously restricted to men of property. Moreover, the new career of philanthropy defined by Hannah More provided a practical means by which women of all classes could actively construct a new British civil society, and thus become the mothers not only of individual households but of the nation as a whole.

"Intellectual and social historians (and not just feminists) have long believed that the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain saw an increasing separation of the male (public) and female (domestic) realms, with the result that the public sphere theorized by Jurgen Habermas and others to have emerged in the Enlightenment almost entirely excluded women. With energy, wit, and admirable command of her sources, Mellor . . . author of distinguished books on Romanticism . . . demonstrates that just the opposite was true: in the years around 1800, women became the primary producers and consumers of writing in Britain and vitally participated in the discursive public sphere—many arguing in their different ways for what Hannah More (the most popular author of the period) called a moral revolution in the national manners and principles. . . . [A] splendid survey of women novelists, poets, critics, playwrights, and social theorists . . . this bracing and important work of revision deserves a place in serious academic libraries serving both undergraduates and advanced scholars." —D. L. Patey, Choice

British women writers were enormously influential in the creation of public opinion and political ideology during the years from 1780 to 1830. Anne Mellor demonstrates the many ways in which they attempted to shape British public policy and cultural behavior in the areas of religious and governmental reform, education, philanthropy, and patterns of consumption. She argues that the theoretical paradigm of the "doctrine of the separate spheres" may no longer be valid. According to this view, British society was divided into distinctly differentiated and gendered spheres of public versus private activities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,

Surveying all the genres of literature?drama, poetry, fiction, non-fiction prose, and literary criticism?Mellor shows how women writers promoted a new concept of the ideal woman as rationally educated, sexually self-disciplined, and above all, virtuous. This New Woman, these writers said, was better suited to govern the nation than were its current fiscally irresponsible, lecherous, and corruptible male rulers.

Beginning with Hannah More, Mellor argues that women writers too often dismissed as conservative or retrogressive instead promoted a revolution in cultural mores or manners. She discusses writers as diverse as Elizabeth Inchbald, Hannah Cowley, and Joanna Baillie; as Charlotte Smith, Anna Barbauld, and Lucy Aikin; as Mary Wollstonecraft, Charlotte Reeve, and Anna Seward; and concludes with extended analyses of Charlotte Smith's Desmond and Jane Austen's Persuasion. She thus documents women writers' full participation in that very discursive public sphere which Habermas so famously restricted to men of property. Moreover, the new career of philanthropy defined by Hannah More provided a practical means by which women of all classes could actively construct a new British civil society, and thus become the mothers not only of individual households but of the nation as a whole.

"Intellectual and social historians (and not just feminists) have long believed that the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain saw an increasing separation of the male (public) and female (domestic) realms, with the result that the public sphere theorized by Jurgen Habermas and others to have emerged in the Enlightenment almost entirely excluded women. With energy, wit, and admirable command of her sources, Mellor . . . author of distinguished books on Romanticism . . . demonstrates that just the opposite was true: in the years around 1800, women became the primary producers and consumers of writing in Britain and vitally participated in the discursive public sphere—many arguing in their different ways for what Hannah More (the most popular author of the period) called a moral revolution in the national manners and principles. . . . [A] splendid survey of women novelists, poets, critics, playwrights, and social theorists . . . this bracing and important work of revision deserves a place in serious academic libraries serving both undergraduates and advanced scholars." —D. L. Patey, Choice

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mothers of the Nation by Anne K. Mellor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Women in History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Hannah More, Revolutionary Reformer

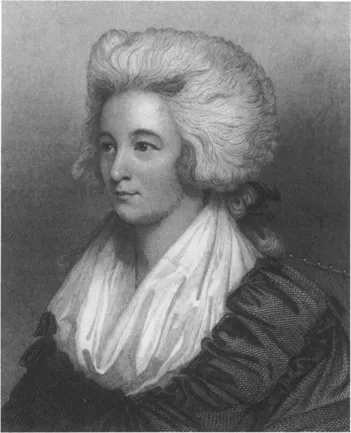

3. John Opie, HANNAH MORE, eng. J. C. Buttre for The London Repository, 1861.

Hannah More was the most influential woman living in England in the Romantic era. Through her writings, political actions, and personal relationships, she promoted a successful program for social change from within the existing social and political order. In this chapter, I make five claims concerning the historical impact of More’s career. (1) Her writings contributed to the prevention of a French-style, violent revolution in England. (2) They did so by helping to reform, rather than subvert, the existing social order. (3) This reform was four-pronged: it was directed simultaneously at the behavior of the aristocracy, at the behavior of the clergy, at the behavior of the working classes, and at the education and behavior of women across all classes. (4) In an era of greatly expanding imperialism and consumption, she moralized both capitalism and consumption. (5) So profound were these social changes that one can plausibly say that Hannah More’s writings consolidated and disseminated a revolution, not in the overt structure of public government, but, equally important, in the very culture or mores of the English nation. These are bold claims which I must now try to support.

Before I do, I should enter one caveat. In this book, I use the term “revolution,” as in my deliberately provocative chapter title, to refer to cultural and social revolutions, as well as to political revolutions. If a verbal campaign has the effect of markedly transforming the everyday social practices and lived experience of the majority of the inhabitants of a community or nation, then that campaign has brought about an overturning, or revolution, in the culture or mores of that nation, even when no change in the constitutional structure of the state government has occurred. I here draw on the specific valence that the word “revolution” carried in the late eighteenth century. As Raymond Williams has noted in his Keywords, in the 1790s “revolution” meant “making a new social order,” either through the violent overthrowing of the old order increasingly associated in political discourse with the French Revolution or through “peaceful and constitutional means,” as the result of profound and effective social reform (229).

The enormous influence of Hannah More on her contemporaries was widely acknowledged in her lifetime; as Georgiana, Lady Chatterton, commented with some asperity in 1861, “half an hour’s conversation with any Somersetshire octogenarian, whose memory of events can go back clearly into the last twenty years of the last century, will convince anyone (not grossly prejudiced) that Hannah More rendered national services of unappreciable extent” (Chatterton I: 146). Sixty years after More died, Canon Overton, writing on the history of the English church in the nineteenth century, insisted that “It is hardly too much to say that she was the most influential person—certainly the most influential lady—who lived at that time” (Overton; qtd. in Meakin x–xi). Her fame spread far beyond England. The early American feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a woman in a position to know, best summed up More’s contribution to her age in 1848:

It has happened more than once that in a great crisis of national affairs, woman has been appealed to for her aid. Hannah More one of the great minds of her day, at a time when French revolutionary and atheistical opinions were spreading—was earnestly besought by many eminent men to write something to counteract these destructive influences—Her style was so popular and she had shown so intimate a knowledge of human nature that they hoped much from her influence. Her village politics by Will Chip, written in a few hours showed that she merited the opinion entertained of her power upon all classes of mind. It had as was expected great effect. The tact and intelligence of this woman completely turned the tide of opinion and many say prevented a revolution, whether she did old Englands poor any essential service by thus warding off what must surely come is a question—however she did it and the wise ones of her day gloried in her success. Strange that surrounded by such a galaxy of great minds, that so great a work should have been given with one accord to a woman to do. (Stanton 112–13)

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century biographers have continued to affirm More’s overwhelming impact on the British nation during her lifetime. Clara Balfour observed in 1854 that despite her “comparatively humble station” and the fact that her age was “not favorable to women’s mental elevation,” Hannah More nonetheless became a “person of such influence, that no contemporary female name ranked higher in the list of educational and literary benefactors” and further, “came to be the favorite companion of the learned and the noble, and the monitor both of peasants and princes” (Balfour 4–5). F. K. Prochaska, in his definitive study of women and philanthropy in nineteenth-century England, again concluded in 1980 that Hannah More was not only “the most influential female philanthropist of her day” but also “probably the most influential woman of her day” (6). Al-most certainly, as A. D. Harvey comments, she was “the most successful propagandist of the 1790s” (1978: 106).

Why then has Hannah More been so relentlessly condemned by, even on occasion erased from, the most widely read historical accounts of England in the early nineteenth century? This is so much the case that the recent, and very fine, study of Hannah More’s life and works by Patricia Demers in 1996 begins with an apology for taking her work seriously (Demers, pref-ace). My answer, albeit speculative, is simple. The leading historians of eigh-teenth- and nineteenth-century England have emerged from a theoretical tradition grounded on Marxist or left-wing socialist ideologies: they hate Hannah More because in their eyes she did far too much to stop a liberating French-style political revolution from occurring in England. In the mid-1790s, More’s widely disseminated Cheap Repository Tractswere often credited with preventing rebellion and thereby saving the monarchy in England. Numerous commentators—Henry Thompson and Thomas Taylor in 1838, Marion Harland in 1900, Sam Pickering again in 1976 (Thompson 158; Taylor 154; Harland 176–77; Pickering 35)—have noted that in 1795, rioting colliers both at Bath and at Hull were calmed by a singing of More’s cautionary ballad “The Riot, or, Half a Loaf is Better than No Bread.” As Ford K. Brown observes, More’s friends considered her to be “the chief agency in checking the flood of philosophy, infidelity and disrespect for inherited privilege that poured fearfully across the Channel from 1790 on” (123).

The negative press on Hannah More has been deafening, from British social historians and literary critics alike. E. P. Thompson summed up the charges against More in The Making of the English Working Class in 1963, in which he accuses More and her allies of nurturing a fear of social change among the landed gentry so powerful that “in these counter-revolutionary decades … the humanitarian tradition became warped beyond recognition” (61). He further denounces her most philanthropic project, the construction of Sunday Schools for workers, as an exercise in “discipline and repression” in which the bourgeoisie brainwashed the working classes into submission (441). Here Thompson joins the assault on More begun fifty years earlier by John and Barbara Hammond, who in 1917 in their The Town Labourer condemned the entire Evangelical movement as well as the Sunday Schools it fostered as an attempt to reconcile workers to their misery on earth and to persuade them to let the rich “do their thinking for them” (Hammond x). As the Hammonds powerfully concluded their critique of More and her allies:

The working classes were therefore regarded as people to be kept out of mischief, rather than as people with faculties and characters to be encouraged and developed. They were to have just so much instruction as would make them more useful work people; to be trained, in Hannah More’s phrase, “in habits of industry and piety.” Thus not only the towns they lived in, the hours they worked, the wages they received, but also the schools in which some of their children were taught their letters, stamped them as a subject population, existing merely for the service and profit of other classes. (51)

So persuasive has been the Marxist claim that Hannah More participated in an oppressive project of “social control,” as Robert Hole and Morag Shiach have recently defined it (Hole 135–41, Shiach 86), in what Foucault would call a discourse of discipline and punishment, that to date no British social historian has defended her career. Some, like Philip Corrigan and Derek Sayer in their The Great Arch: English State Formation as Cultural Revolution (1985), simply omit her from their account. But most follow E. P. Thompson in seeing her as opposed both to reform and to free thought, as do R. K. Webb, V. Kiernan, and M. J. Crossley Evans. In The British Working Class Reader, Webb dismisses her Cheap Repository Tracts as “anti-reform” (42, 56). Kiernan, in an influential essay on “Evangelicalism and the French Revolution” that appeared in Past and Present in 1955, focuses entirely on the “negative” aspects of the Evangelical movement as a social agent which contributed to “preserving an essentially static social order” (44); while Evans more broadly condemns her as “anti-Enlightenment” (460).

Even her humanitarian efforts as a philanthropist have been downplayed by David Owen in his highly regarded study English Philanthropy 1660- 1960 (1964). Owen condemns Hannah More’s and Sarah Trimmer’s Sunday Schools as “patronising” the poor and putting a “sinister stamp on nineteenth century charity,” although, he claims, luckily they were on the “losing side” (92, 99–100). The rancorous undercurrent to much of the historical commentary on More’s career erupts into full view with William Richardson’s description of her in 1975 as a “necrophiliac … opportunist” who “flattered and fawned” her way into society, whose Cheap Repository Tracts were “designed to instill anti-intellectualism, intolerable pride of class, and complacent awareness of their own virtue” among the “middling sort,” and whose ideal woman Mrs. Simpson is a “singularly repellant female Job,” “the prototype of all the long-suffering soap opera heroines who ever … castrated a male a week upon the altars of their implacable virtues” (230, 232, 235).

On the whole, Hannah More has fared no better at the hands of literary critics, even feminist ones. Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace defined her as the quintessential “daddy’s girl,” a willing participant in a patriarchal order who used the Evangelical movement to position herself as “the social ‘superior’ to her lower-class sisters” (1991: 56–93). Lucinda Cole reads her as advocating the silencing of women (120–24), while Cannon Schmitt invokes her as the leading propagandist for an almost Gothic “internal surveillance” of the “unruly” female self (28–32). Alan Richardson defines her educational program as “anti-feminist” and designed to support a traditional patriarchal society rather than to alter woman’s social position (1994: 180–81). Gary Kelly sees her writings as an apologia for “rural paternalism” (1987: 150), while Claire Grogan similarly responds, in the face of recent efforts to gain a more sympathetic hearing for More’s career, that she was relentlessly anti-Jacobin and pro-patriarchal (100). And Mary Waldron, introducing a recent paperback reprint of More’s novel Coelebs in Search of a Wife, can barely contain her irritation with More’s propaganda for “the stability of the existing order,” for “quietism and stasis,” concluding that the novel is now no more than a “sometimes slightly horrifying, historical curiosity” (Waldron vii, viii, xxx). Elisabeth Jay again condemns More’s literary gifts, insisting that More “accorded little of the aesthetic respect to her tool [the novel] that we might expect from the committed artist” (4).

This judgment on More’s literary achievement echoes many of her contemporaries’ view of her writings. The poet Peter Pindar [John Wilcot] in 1799 condemned Hannah More as a “rhyme-and-prose Gentlewoman, born at Bristol” whose genius is of a “metallic nature,” so much so that he “solemnly protesteth that he cannot wade twice through Miss Hannah’s Works, deeming them, as Dr. Johnson would have expressed himself, pages of puerile vanity and intellectual imbecility” (Pindar 5). William Shaw, writing as the Rev. Sir Archibald MacSarcasm, denounced More’s “information and genius” as entirely “factitious,” insisting that “there is neither invention, genius, plot or description in her dramas,” that her poetry consists of “eight volumes of inanity, much chaff and little wheat,” and concluding that she suffers from “meanness of mind and a maliciousness of heart” (MacSarcasm 6, 25, 7, 89). The influential Edinburgh Review in 1809 dismissed Coelebs as an “uninspired production” (145). This negative view of More’s literary efforts culminated with Augustine Birrell’s claim that she was

one of the most detestable writers that ever held a pen. She flounders like a huge conger eel in an ocean of dingy morality… . Her religion lacks reality. Not a single expression of genuine piety, of heartfelt emotion, ever escapes her lips. (qtd. in Silvester 119–20)

Reviewing More’s Complete Works in 1894, Birrell concluded that these nineteen volumes constituted an “encyclopedia of all literary vices” which, being unreadable and unsellable, he had buried in his backyard (1894: 71).

Recently, however, More’s achievements have been evaluated more positively by feminist scholars. Beginning with Mitzi Myer’s robust recuperation in 1982 of Hannah More as an effective advocate for the rational education of women on a par with Mary Wollstonecraft, feminists have begun to understand the ways in which More’s writings historically advanced the cause of women’s social empowerment. Kathryn Sutherland in 1991 persuasively argued that More positioned women at the center of a political campaign for domestic and national reform, while Dorice Elliot brilliantly analyzed Coelebs in Search of a Wife as a representation of a new professionalization of women as philanthropists. Most recently, Patricia Demers, in her The World of Hannah More, and Charles Howard Ford in his Hannah More: A Critical Biography, also published in 1996, have provided finely nuanced and sympathetic—if sometimes overly defensive—reassessments of More’s career. My view of Hannah More’s historical achievement is very much in accord with these critics.

I

Rather than promoting the political revolution urged by the French Jacobins or the proletarian revolution of the workers later envisioned by Marx, Hannah More devoted her life to reforming the culture of the English nation from within. She called for a “revolution in manners” or cultural mores, a radical change in the moral behavior of the nation. Writing in an era which she considered one of “superannuated impiety” (Estimate of the Religion of the Fashionable World II: 316), of notable moral decline marked by “the excesses of luxury, the costly diversions, and the intemperate dissipation in which numbers of professing Christians indulge them-selves” (II: 309), More set out to lead “a moral revolution in the national manners and principles” that would be “analogous to that great political one which we hear so much and so justly extolled” (II: 296). In so doing, as Gerald Newman recognized, she powerfully criticized, rather than supported, the existing social order (1975: 401).

More fought her moral revolution on four fronts. Confronted with the decadent practices of the late-eighteenth-century aristocracy—with codes of behavior that licensed libertinism, adultery, gambling, dueling, and fiscal irresponsibility (Jaeger 54–6)—she first attacked the highborn members of “Society.” Although generally overlooked, the Cheap Repository Tracts of the mid-1790s contain as trenchant a critique of the morally irresponsible aristocracy as of the revolutionary workers. In Village Politics, for instance, Jack Anvil the blacksmith, while warning workers against the evils of violent rebellion, nonetheless recognizes the evils perpetrated by the “great folks”: “I don’t pretend to say they are a bit better than they should be … let them look to that; they’ll answer for that in another place. To be sure, I wish they’d set us a better example about going to church, and those things: … They do spend too much, to be sure, in feastings and fandangoes.” And, he concludes, “my lady is too rantipolish, and flies about all summer to hot water and cold water” (II: 230).

In two major tracts addressed directly to the upper classes, Thoughts on the Importance of the Manners of the Great to General Society (1788) and An Estimate of the Religion of the Fashionable World (1790), Hannah More directly condemned the hypocrisy of the “merely nominal” Christians among the aristocracy. Since the rich and powerful are perforce the role models for the lower classes, they have an increased social responsibility to set a good example, More argued. She pointed out all the ways in which the leaders of her time were failing in that civic responsibility: they did not attend church, or did so half-heartedly, combining Sunday services with visiting, concerts, and hairdressing; they gambled, even the women, at card parties in their own homes, using their winnings to tip the servants of the hostess; they engaged in a sustained practice of social lying, forcing servants to tell visitors they were “not at home”; they tolerated adultery, especially for hus-bands; and they systematically failed to develop an appreciation of what was for More the center of personal and social fulfillment—”family enjoyment, select conversation, and domestic delights” (Manners of the Great II: 285). Their behavior thus corrupted rather than educated their servants, forcing these servants to lie, encourage gambling, cheat, and steal.

More calculatedly attributed the amoral practices of the rich to their excessive dependence on French fashions and behaviors. By identifying aristocratic English society with France, at the v...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Women and the Public Sphere in England, 1780–1830

- 1. Hannah More Revolutionary Reformer

- 2. Theater as the School of Virtue

- 3. Women’s Political Poetry

- 4. Literary Criticism, Cultural Authority, and the Rise of the Novel

- 5. The Politics of Fiction

- Postscript: The Politics of Modernity

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index