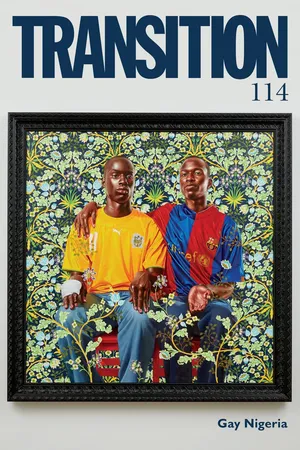

![]()

Gay Rights in Nigeria

ON JANUARY 13, 2014, President Goodluck Jonathan of Nigeria signed into law the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act—more commonly and honestly called simply the Anti-Gay Law. It in effect prohibits identifying as an LGBTQ person, an act punishable by fourteen years in prison. The law also assigns draconian punishment to anyone who knows that someone is gay and does not report that person to the authorities—a “crime” for which the law prescribes ten years of imprisonment. In the extralegal world of vigilantism, the law has declared open hunting season on suspected homosexuals, who are now being rounded up, publicly humiliated, beaten senseless by mobs, or disappeared entirely.

For regular readers of Transition, it will come as no surprise that the editors believe that LGBTQ rights are universal human rights. However, a statement of position alone does not bring us closer to understanding the complex and shifting sociopolitical terrain from which grows the Nigerian law—not to mention the similar laws (or calls for them) that have arisen throughout sub-Saharan Africa, in countries as different from each other as Uganda, Malawi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Cameroon, Liberia, Gambia, and Ethiopia.

Therefore, in an effort to foreground particularity, Transition offers a close look specifically at Nigeria’s Anti-Gay Law. Ayo Sogunro, a Nigerian lawyer, explores the history of Nigerian jurisprudence as it relates to the law, and offers general comments about how it fits into the context of Nigerian society. Rudolf Gaudio, an expert on queer sexuality in Hausaland (Northern Nigeria), argues that the battle against an imaginary gay foe only makes sense if one acknowledges that Nigerian heterosexuality, as conventionally defined, has all but collapsed. We conclude by interviewing Davis Mac-Iyalla—a Nigerian gay rights activists living in exile in London—about growing up gay in Nigeria and the LGBT advocacy work that he does in the Anglican Church.

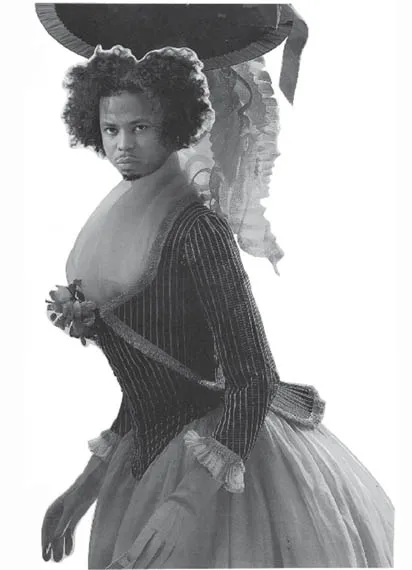

Dressed Up 1. Archival digital photograph. 84 × 60 in. Edition of 3. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC. ©2010 Marcia Kure.

![]()

One More Nation Bound in Freedom

themes from the Nigerian “Anti-Gay Law”

Ayo Sogunro

Ironies and Dichotomies

THE TITLE OF this piece is partly lifted from the first stanza of the Nigerian national anthem. The unintended irony in the phrase is a demonstration of Nigeria’s dalliance with contrasting philosophies and a generic, if simplified, explanation for the emergence of anti-LGBT legislation in the country, despite the absence of any public crisis on the issue.

Nigeria has always suffered from an overdose of ironic circumstances: this is evident from its inception as a geopolitical amalgamation of two distinct sociopolitical administrations—now bound in freedom—to the current international perception of Nigerians as a resourceful yet not-quite-trustworthy people. This irony permeates every stratum of Nigerian psychology, creating contrasting influences and generating continuous tension between the energetic developmental resources available to the country and the negative fallouts from its historical—traditional, colonial, and national—biases, finally culminating in a social stasis—an orbital lock, you may say—that has left Nigeria at a sociopolitical maturity level no higher than that which it possessed on October 1, 1960, when it gained its independence.

Nigeria has always suffered from an overdose of ironic circumstances.

This is no flippant statement. Nigeria has neither progressed by reference to economic or sociopolitical indices (especially in the way that a number of other Commonwealth countries have), nor has the country actually disintegrated—the Civil War notwithstanding—at least, not in the way that observers have forecasted since the late 1960s.

Today, the recent passage of the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act (the “Anti-Gay Law,” for our convenience) is not excluded from the ironic and contrastive Nigerian social psychology. This persistent social psychology makes it clear that there is never a single Nigerian answer to any question of policy; and an external observer would be properly astonished at the range of contrasting social themes that, as the Anti-Gay Law has demonstrated, could eventually emerge as another bewildering aspect of Nigerian public policy. The following paragraphs highlight some of the social and legal themes that propel the peculiar enactment of a law that, as Navi Pillay observes, “in so few paragraphs directly violates so many basic, universal human rights.”

Relationships: Sex or Marriage?

The principal intent of the law, eponymously self-evident, is the prevention of homosexual marriages in Nigeria. But, consider the following argument:

Fact 1: Marriage is necessarily a socio-legal system-sanctioned arrangement.

Fact 2: The existing socio-legal systems in Nigeria are incompatible with a homosexual marital relationship.

Fact 3: The Anti-Gay Law exists.

Conclusion 1: The Anti-Gay Law seeks to prevent a type of marital relationship that is already incompatible with the existing socio-legal systems.

Conclusion 2: The Anti-Gay Law serves no purpose under the Nigerian socio-legal systems for marital relationships.

The foregoing is as valid an analysis as one can manage if solely focused on the marriage issue. But the second conclusion above remains valid only if one believes that the principal intent of the law, eponymously self-evident or not, is the prevention of homosexual marriages in Nigeria. However, no Nigerian really believes that. The recent court cases in Nigeria indicate—and we all know—that the law is not about preventing same sex marriage, instead it is about preventing—or more accurately, punishing—same-sex intercourse and, more broadly, homosexual identity. But a law that claims only to be against “Same Sex Marriage” sounds nicer. Because, you see, Nigerians are nice people.

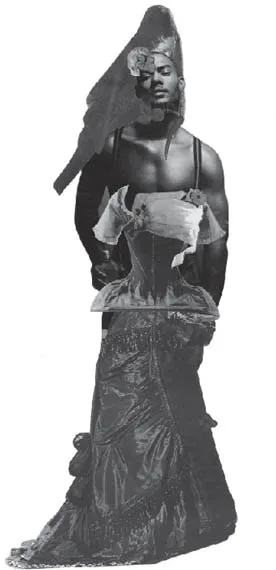

Dressed Up 3. Archival digital photograph. 84 × 60 in. Edition of 3. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC. ©2010 Marcia Kure.

Foundations: What Culture, What Religion?

The most common rationale for the Anti-Gay Law that one hears is that homosexuality is anathema simultaneously to Nigerian culture and to Nigerian religion. However, consider this: the Nigerian cultural identity comprises up to 250 (or 102, depending on your criteria) ethnicities with varying, and sometimes opposing, cultural norms, most of which have been sacrificed, in any case, at the altars of Nigeria’s main religious identities, Christianity and Islam. The argument that homosexuality is not a part of the Nigerian cultural heritage therefore becomes subject to ridicule when one considers the variety of cultural norms in Nigeria, and the dismissive treatment casually meted out to these cultural norms after the advent of Christianity and Islam.

Acceptance of the religious argument in support of the Anti-Gay Law requires a convenient disregard of the amoral religiosity of Nigerian society.

This leaves us with the religious argument, and in Nigeria, that is an argument to be respected, somewhat. No other country in the world, probably, takes as much pride in its public piety as does Nigeria. Public and private functions, whether commercial or non-profit, are commenced and ended with prayers. The church industry is “big business,” one whose annual turnover—if such measurements exist—would rival those of the banking and telecommunications industry. The Islamic oligarchy is in firm control of the North; in the South, the mere title of Alhaji—one who has gone on a pilgrimage to Mecca—is treated with maximum social respect. There are many more examples of Nigeria’s religious bedrock: its permutations are endless.

Yet, Nigeria is listed as a high-ranking corrupt officialdom, its elections are consistently flawed, and its passport is universally suspected. In fact, displays of moral extremism and religious fanaticism are not considered to be socially acceptable virtues in Nigeria. Even the introduction of the Sharia legal system in certain parts of the North was generally opposed, and it only became tolerable after the explanation that its application was via the personal choice of law of the litigants, or the accused. Across the country, the entertainment industry has a materialistic nature, and a Hollywood-style philosophy permeates the pop culture.

Thus, one could argue that the religious nature of the country is superficial, rather than principled—and this hypocrisy is generally tolerated in everyday Nigerian life. Consequently, it is highly uncharacteristic, by Nigerian standards, for a religious argument to be the prop for any governmental regulation—or worse, a federal law—and more so when the Constitution of the country unequivocally disavows a state religion.

Dressed Up 5. Archival digital photograph. 84 × 60 in. Edition of 3. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC. ©2010 Marcia Kure.

In short, acceptance of the religious argument in support of the Anti-Gay Law requires a convenient disregard of the amoral religiosity of Nigerian society. It would then be an error of judgment for an observer to fail to challenge this rationale, especially on a premise that Nigerians scrupulously desire a theocratic legal system. If such a fantastic idea were to be implemented, the political, administrative and commercial structure of the country would crash. And every Nigerian knows this.

A Nigerian politician may cheerfully announce to his audience that the passage of the Anti-Gay Law is a reflection of the wishes of the majority of Nigerians. Considerations about the fairness of majority numeric strength versus minority human rights aside, such a statement would still be incorrect. While it is true that a great number of Nigerians are religiously, and to an extent culturally, disapproving of homosexual relationships, there also exist a fair number of such disapproving Nigerians who believe that public interference in private consenting sexuality is not within legislative competence. These Nigerians believe the law to be a greater evil than the sexuality it seeks to curb. There are no existing statistics to gauge the exact percentage of these Nigerians, but this much is clear: the legislative philosophy that birthed the law did not account for this category. To sum it up, Nigerians, in general, tend to adopt a “live and let live socio-cultural philosophy,” and while the majority of Nigerians are clearly not in support of homosexuality, not all of these Nigerians are directly anti-homosexual or, more properly, homophobic.

Criminal Jurisprudence: Colonial Legacy or Modern Democracy?

Nigeria’s criminal law, excepting public corruption offences and commercial law offences, is cryogenically embalmed in a colonial pod. A few states, like Lagos, often review these colonial relics and upgrade them to meet modern social requirements, but, overall, the criminal legal system, and its underlying jurisprudence, remains essentially unmodified from their British shape.

Accordingly, the general Nigerian criminal code is peppered with Victorian Era morality, crudely adapted to local conditions by the colonial government to ensure proper administration, and resulting in ridiculous propositions such as the allowance of corporeal punishments; misogynist limitations of certain criminal responsibility; and, of course, the infamous series of “unnatural offences,” including this,

. . . any person who permits a male person to have carnal knowledge of him or her against the order of nature. . . is guilty of a felony, and is liable to imprisonment for seven years,

a legal provision which somehow weds sexism to incomprehensible legalese. The law has no definition of what exactly constitutes the “order of nature,” and the interpretation is left to the personal tolerance of the trial judge.

This nineteenth century punitive criminal system was further amplified by the long years of military rule and repressive policies. Under the recurrent military regimes, legislative authority derived from the decrees of the military “head of state”—and a crime was simply what the head of state declared to be a crime, even if retroactively. As a rule, the military had no use for, in the infamous words of then-General Buhari, “the nonsense of legal proceedings.”

Dressed Up 10. Archival digital photograph. 84 × 60 in. Edition of 3. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC. ©2010 Marcia Kure.

With this historical excursion in view, it is easy to see how Nigeria’s criminal jurisprudence is largely punitive and repressive in nature. Reformative criminal laws are a novelty, and individual liberty within the social context is almost non-existent in the criminal law jurisprudence. Set in tension with this is the fact that constitutional democracy—as entrenched in the current Nigerian Constitution—is much more tolerant than the criminal laws will allow. However, while very few Nigerians are familiar with the principles of constitutional democracy (particularly because of its relatively recent application in 1999), almost every politically conscious Nigerian is aware of the punitive philosophy embedded in the criminal laws. That punitive ideology often flare...