eBook - ePub

We Only Come Here to Struggle

Stories from Berida's Life

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Kenyan trader shares her life history, including enduring British colonial rule, overcoming poverty, and reclaiming her life.

Here is the life history of Berida Ndambuki, a Kenyan woman trader born in 1936, who speaks movingly of her experiences under the turbulences of late British colonialism and independence. A poverty survivor, Berida overcame patriarchal constraints to reclaim the rights to her labor, her body, and her spirit. She invokes a many-faceted picture of central Kenyan life in this compelling narrative.

Here is the life history of Berida Ndambuki, a Kenyan woman trader born in 1936, who speaks movingly of her experiences under the turbulences of late British colonialism and independence. A poverty survivor, Berida overcame patriarchal constraints to reclaim the rights to her labor, her body, and her spirit. She invokes a many-faceted picture of central Kenyan life in this compelling narrative.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access We Only Come Here to Struggle by Berida Ndambuki,Claire C. Robertson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“I Am Berida Ndambuki”

Childhood, Family, and Initiation

My name is Berida Ndambuki1 but it was not always so. My birth name was Mathei wa Moli (my father’s name) wa Kivinda (my grandfather’s name). That’s how we do it. My mother’s name was Maria Mbatha. But now I am Berida Ndambuki. Ndambuki is my husband. He married me when I was young. But in 1957 after attending catechism class for four years I was given the name Berida, and everyone calls me that except Ndambuki when he is being bad. He then uses Mathei but he is the only one that does that. After I took more classes I was given the name Lucia to show that I am a complete Christian and accept Jesus. It is fine for you to use my real name here and those of my family; maybe if my husband sees how he looks here he will change his ways.

About myself, when I was married by Ndambuki I became a dutiful wife. We stayed together as husband and wife and got children but we were very poor and we had no employment, so it became necessary for me to come to Nairobi so that we could educate our children. I educated two children, Magdalena and Angelina. But first maybe I should tell you about my childhood so you can see how things have changed.

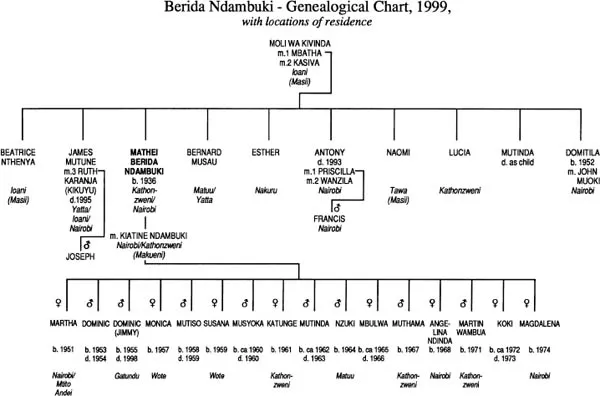

I was born in 1936 at Masii in the district of Machakos.2 Masii is very beautiful; we lived at a place called Iiani. I loved it because we were all there, my father, my mother, my brothers, and my sisters. I grew to be a big girl there and danced the Akamba dances there. I eventually married in 1950. My mother had ten children; I had an elder brother and an elder sister, two younger brothers, and five younger sisters. The eldest is Beatrice, then James Mutune, who died last year of diabetes, then me. After me came Bernard Musau, who is several years younger, Esther, Antony, who died in 1993, Naomi, Lucia, Mutinda, who died young, at about age twelve, and the last-born is Domitila, who was born in 1952 and went to school. I also have half-brothers and sisters since my father had three wives.

Genealogical Chart: The Family of Berida Ndambuki

John Hollingsworth, Indiana University Cartographer

John Hollingsworth, Indiana University Cartographer

My father’s clan, to which I belong, is called Mwanzio, Wa Muthike, or Muthike (my children belong to Ndambuki’s clan). We were told that Muthike was buried so that rain would come. Daughters of our clan are supposed to be very valuable because we are the ones who brought rain. For the same reason we are supposed to be the first ones to plant after the rains come. We are good farmers. You should see my farm when we have rain; I plant maize, cowpeas, and pigeon peas. There is a tree at Kilala in Makueni that is sacred and the subject of the story we were told about our past. It grows, matures, dries out, and then another shoot comes up. It never dies. This story is about Muthike, a girl.3 There was a drought. The diviners consulted with other diviners and were told to bury the girl and the rain would come. They gathered together cows to take to the girl’s father for her, everyone in the neighborhood contributing, but they didn’t tell the girl. She had taken her father’s cattle to the bush to graze and the father told them to go look for her there. They found her and she said, “Get someone to stay with my father’s herd.” They got someone. Then she said, “Cut a stick for me from the mumo tree.” The stick was cut for her and a cow was killed. A grave was dug. She told them to smear its hide with oil and put it on top of the grave so she could see it. She told them she was going to go and that they should run fast to their homes because it was going to rain. She went singing, holding the stick, which had also been smeared with oil. She fell into the hole still holding that stick and remaining upright. When she fell it rained a lot and the grave was filled with water. She drowned. The stick she was holding grew and sprouted breasts. The whole place was covered with water and sweet potatoes grew there. People began to call the place Kwa Muthike. So that’s why our clan is called Muthike’s.4

Back then we dressed differently from nowadays and even ate different food. We used to cover ourselves with a piece of black cloth the way the Maasai tie themselves over the shoulder. It was tied with sisal string. The rest of the body was left uncovered. It was that black nylon cloth like umbrellas are made of and we bought it from the wahindi [Kiswahili; Asians/Indians]. It used to cost fifteen cents. My mother used to tie her cloth on both sides so that all of her parts were covered; she did not wear anything underneath. But my grandmother sometimes used to wear a goatskin when a goat had been slaughtered. It was kneaded and then joined together at one place so that she could just slip it on. The kneading made the hide soft. It was fastened on one shoulder with a piece of skin or a piece of bark fiber from a tree called kiamba [baobab] that was also used to make baskets. She used goatskin also as bedding. My mother did wear a goatskin sometimes, but only on her back when she went to scoop water from the wells in the sand or when she carried bundles of thorny kindling. People wore hides so they could get through the thorns without being pricked, but I never wore one. My mother and grandmother used to wear their hair short and rub it into thick little balls; they looked like buttons and stood out from their heads. When they got tired of rubbing it they would shave it off like the Maasai. My grandmother would shave the crown of her head and then leave a little hair around the outside where she would put beads.

Another thing people used to do was to remove certain teeth because, if they hadn’t been removed, you could not share a dish with those who had had them removed. Those people would say that they could not share a plate with someone who had to “force food over a bridge [the teeth].” It was considered to be beautiful or fashionable to remove two bottom front teeth.5 We also pierced our ears and put ornaments in them to make ourselves beautiful. The ornaments were made of wood, carved and shaped by men, smoothed with stone, shiny, and fitted into the girls’ ears. My mother did that and my ears were pierced too. I still have the ornaments at home. But I am not wearing them now, why should I? I’ll do it when you are taking a photo of me to take to your country. When I was about eighteen I had some scars made. There were men who were skilled at such things and we did it to beautify ourselves.

Back then babies used to sleep on goatskins. Because of being constantly peed on the skins would have many folds which often got bedbugs in them. By morning the baby would be covered in bites. The mother would take the skin outside and beat it with a stick to get rid of the bugs then put it back on the bed. The beds then were different too. They used to make their own with sticks and baobab fiber string [demonstrates]. They got four sturdy pieces of wood for the legs and fixed them in holes in the ground. Then they laid other poles lengthwise and placed a mat made with sticks and string on the poles. That was the bed. Then they made a mattress woven with string from grass. This was done by young men. Even when we moved to Makueni in 1964 we made new beds there like that with grass mattresses.

When I was a child we ate pumpkins, sweet potatoes, and sorghum millet ground fine then cooked in milk to make a dish called kinaa.6 It could be eaten raw too if you were really hungry. The grinding was done by hand using two stones, the lower one flat and big and an upper smaller one. The millet was ground until it was very soft. We didn’t eat a lot of greens, but what could happen was that during the dry season or a famine when there was only flour to eat it would be cooked together with some greens to make a dish called ngunza kutu. Sometimes the greens were nthoko [cowpea] leaves, or they might be kikowe, long thin leaves, or ua [amaranthus leaves]. We cultivated the nthoko leaves but the kikowe were wild.7 Then everyone would be given their share. We didn’t eat maize like we do now; where would that have come from during a drought? There were many problems. Even cows were felled and bled so that we could cook the blood to eat. When there was food we cooked isyo [food—maize and beans]. We could also pound maize and get flour, then cook it. Normally we ate that one day, and the next we might have ngima [a dish made from maize flour], and the day after that kiteke [millet flour and milk]. We also might alternate eating pumpkins and sweet potatoes.8

We worked a lot, hauling water and watching cows, but we also played games. I was good at games. We would collect wild fruits and pretend they were cows; we sometimes modeled cows and sheds out of mud and pretended we owned them. I played with the neighbors’ children and relatives; we competed to see who could make the best and most cows. We played with something called kima made using sticks, and another thing called bila which looked like this [demonstration]. That was mainly used by boys; they would hit it with a string tied to a stick so that it went round and round. Kima was made from a pigeon pea plant stalk which is pointed and one threw it. If it hooked onto the specified object then you were the winner. It was also a boys’ game. Girls played with stones. We would take about five stones, throw one up and try to move the rest before the stone came down. That game was called kola.9 We didn’t have bilikoli [marbles] but we would take stones and smooth them using a bigger stone until they were rounded. We all played with the same set of stones. You threw a stone up and tried to catch it. If you failed then you gave the stones to the next competitor.

We also had jumping games and dances. We would run and try to snatch something from each other like ngondu [a wild fruit]10 or we would have races to see who was the fastest. We might also fight to see who was the strongest. If you won, your prize was only that you would be feared and nobody would pick on you! [Laughter.] I was never beaten by anyone. As I grew older I saw people participating in school athletics. They would call on me to run; I was very fast and won many prizes even as an adult. I would win things like blankets, lanterns, plates, soap, spoons, and washbasins. I ran for the school from my home area, Kabaa school, even though I wasn’t in school. The teacher really liked me, especially the one they called captain. He would come looking for me calling out my name [she laughed]. If we won locally we would then travel to Masaku to compete. There was a dance called mbeni and another called kilui [crow] in which you stretched your neck and hands and strutted like a crow. But old women danced without a lot of jumping, something called kilumi, bum, bum, bum, bum, bum, bum [demonstrates]. We still do it.11

I even did things that were supposed to be for boys, like the high jump, called ndui. We would put poles at two ends and then lay one between them and jump. We would also go where there was a slope and slide down on our bottoms. Boys and girls did that separately at their own places. There was nothing that a boy could do that I could not do. Even if they wanted to fight, I would fight with them and no boy could beat me. I was arrogant even as a small girl; if a kid came and asked me, boy or girl, what I was saying, I would just hit them. You know, my father liked me very much and he was arrogant. Yes, I often acted more like a boy than a girl, and my father would ask, why was I born a girl instead of a boy? Sometimes the other kids would laugh at me and say that I was like a boy. They would even spit on me. And if a boy behaved like a girl the other kids would also laugh at him and call him a girl. We were told that a boy should not behave like a girl but be brave since they would be called on to fight when there were raids or cows had been taken. Boys who lacked courage were never taken to fight; they were cowards like women. Women were timid. But I am not timid. It depends on how you are created. There are people who are timid and scared and look like they are sleeping all the time. Do you want to tell me that that is a person? [Laughter.] Why, if they saw Kilaya, who is white, they would move backwards and start talking in low tones, [whispering] “Who is that?” Such people will never progress at all. But if I had gone to school, by now I would be in Parliament!

I did not go to school because my father was a drunkard and did not send me.12 So for languages I know mostly Kikamba, but also some bad Kiswahili, and Kikuyu, no English. And I can read my name but I can only write a few letters of it; I have to use a cross to sign things. I learned Kiswahili from selling at Gikomba. An African can never accept the price that you give so they bargain. They will ask, [Kiswahili] “How much is it? What is it? What is it?” That’s how I came to learn it. Once I went for some adult education, but only for two days. The problem was that while I was listening I kept being distracted by thinking about my children, whether or not they had enough to eat and so on. I quit so I could deal with all those problems. I really wish I had gone to school so I could read and speak English, be as smart as those who have. White people have become so clever, but it’s not that they are white, just that they have education. I feel foolish because I don’t read.

Neither of my parents went to school. My father hasn’t worked for a long time now. He is still alive and living at Masii but my mother died some years ago. He just herded cattle. I really liked my father when I was a child. If you see us together, you will see that I am more like him. My father also liked me because I was sharp. If he sent me on an errand I went running off and came back quickl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Glossary of Frequently Used Terms

- Introduction

- 1. “I Am Berida Ndambuki”

- 2. “No woman can know what will happen to her in marriage”

- 3. “Now I was in business”

- 4. “The Akamba are a peaceloving people”

- 5. “I ask myself, why did I have my children?”

- Update and Analysis: 1999

- Postscript

- Bibliography