![]()

ONE

THE OLD ORDERS

In the World but Not of It

On cold winter mornings all over Indiana, groups of Amish women gather to quilt. Summer work is over, the gardens are clean of all vestiges of summer harvest, and shelves are full of canned fruits and vegetables. Now there is time for neighbors and friends, mothers, sisters, and daughters to work together, piecing material of different colors and shapes into covers that will adorn family beds. Often their handiwork transforms remnants of old sewing projects—the odds and ends of leftover fabric—into beautiful quilts. Although the work is carefully crafted and the stitching is even, the design and color scheme may not be uniform or symmetric.

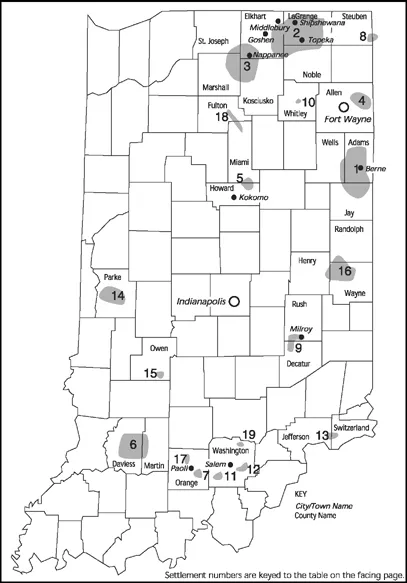

So it is with the Old Orders themselves. Common convictions and diverse traditions produce a particular pattern from the state’s nineteen Old Order Amish and two Old Order Mennonite communities, encompassing more than 35,000 people. Scattered throughout Indiana, Old Orders primarily live in the state’s northeastern quadrant but also in east and west central Indiana, and several communities dot the southern portion of the state (table 1.1). Some of these communities are small, with fewer than a hundred people; others include thousands of Old Orders.

Although the variety within these communities is as colorful and varied as a patchwork quilt, we use the common label “Old Order” to name all those who use horse-and-buggy transportation on the road.1

The Heart of the Old Order Belief System

Although a surprising degree of diversity characterizes Old Order life, Hoosier Old Orders share many elements of faith and practice with one another—commonalities that connect them and that link them with Old Order groups in other parts of the United States and Canada.2 Old Order values stand in sharp contrast to those of modern American society. While Americans champion progress or assume that new is synonymous with improved and that bigger equals better, Old Orders orient their lives around a different set of assumptions. Understanding these values is essential for making sense of Amish life. Four core beliefs—based on their Christian convictions and reading of the Bible—unite all Old Order groups: (1) the individual finds meaning only in the community of believers; (2) there must be a clear and visible distinction between that church community and the larger society (“the world’’); (3) church members should rely primarily on one another and not on institutions of the larger society for support; and (4) the wisdom of tradition is most often a better guide for living life than is the inherently uncertain promises of innovation and change.

Old Order Amish settlements. MAP BY LINDA EBERLY.

Table 1.1. Old Order Amish Settlements in Indiana

| Settlement | Origin | Size in 2002 |

| 1. Berne (Adams-Jay-Wells Counties) | 1840 | 32 church districts |

| 2. Elkhart-LaGrange (Elkhart- LaGrange-Noble Counties) | 1841 | 114 church districts |

| 3. Nappanee (Marshall-Kosciusko- St. Joseph-Elkhart Counties) | 1842 | 33 church districts |

| 4. Allen County | 1844 | 14 church districts |

| 5. Kokomo (Howard-Miami Counties) | 1848 | 2 church districts |

| 6. Daviess-Martin Counties | 1868 | 19 church districts |

| 7. Paoli (Orange County) | 1957 | 2 church districts |

| 8. Steuben County, Ind./Williams County, Ohio | 1964 | 2 church districts |

| 9. Milroy (Rush-Decatur Counties) | 1970 | 4 church districts |

| 10. South Whitley (Whitley County) | 1971 | 1 church district |

| 11. Salem (Washington County) | 1972 | 1 church district |

| 12. Salem (Washington County) | 1981 | 2 church districts |

| 13. Vevay (Switzerland-Jefferson Counties) | 1986 | 2 church districts |

| 14. Parke County | 1991 | 4 church districts |

| 15. Worthington (Owen-Greene Counties) | 1992 | 1 church district |

| 16. Wayne-Randolph-Henry Counties | 1994 | 3 church districts |

| 17. Paoli (Orange-Lawrence Counties) | 1994 | 1 church district |

| 18. Rochester (Fulton-Miami Counties) | 1996 | 1 church district |

| 19. Vallonia (Washington-Jackson Counties) | 1996 | 1 church district |

A traditional Amish farm, east of Goshen, typifies the rural lifestyle popularly associated with the Amish. Although most Amish continue to live in rural areas, today only a minority is engaged in farming.

PHOTO BY DENNIS L. HUGHES.

The Individual and Society

“While Moderns are preoccupied with ‘finding them-selves,’” sociologist Donald Kraybill has noted, “the Amish are engaged in ‘losing themselves.’”3 In sharp contrast to the dominant culture of the United States, which exalts the individual, the Amish believe that in losing their individual identities they will find a stronger identity in their collective community of faith. Based on their understanding of Christian humility, the Amish believe that personal ambitions are secondary to Holy Scriptures, centuries of church tradition, and family obligations. Indeed, the ideal relationship between individual Old Order believers and their community can be described with the German word Gelassenheit, which means submission—to God, to others, and to the church.4 Submission allows the collective wisdom and prudence of the community to govern the priorities of the individual.

Gelassenheit affects nearly every facet of Amish behavior and relationships, from the plain style of clothing and reluctance to pose for photographs, to the general hesitancy to sign their names to public documents or to be quoted by name in the newspaper. When it is time for the all-church noon meal following Sunday morning worship, men and women quietly whisper, “You go first. No, you,” as each seeks to be the last one seated. Gelassenheit suggests that the volume of one’s voice should rarely be raised and that one show deference to others by remaining silent in a moment of uncertainty before replying to a question.

Gelassenheit also assumes that a humble demeanor is far more appropriate than arrogance or pride. Thus an Amish minister will nearly always begin his sermon with a comment about how unworthy he is to preach, and he will ask his flock to bear with him patiently. He will end the sermon by asking fellow ministers to give testimony, inviting them to “please correct what I have said incorrectly” or to add insights of their own. This simple request for correction and embellishment is a regular reminder that no individual has the last word before the body of believers.

Within the family, Gelassenheit emerges in a primary disciplinary task of parents who seek to “break the will of the child” in order to promote a sense of collective consciousness in place of individual willfulness. As soon as children are self-aware, they must learn to respect the tradition of parents and understand what it will mean if they should decide to join the church as adults. Membership requires submission to an authority beyond the self.

Gelassenheit is also directly tied to simplicity. An Amish home is to be furnished modestly. Any ostentation or unnecessary decorations suggest that the homeowner is trying to gain attention. Although some settlements allow upholstered furniture, none permit wall-to-wall carpeting, the display of human portraits, or full-length mirrors.

Symbolic Separation

When a car whizzes past a horse and buggy slowly making its way to town, the car itself reminds the occupants of the buggy of the divide between the assumptions and values of mainstream culture and their own Amish counterculture. The plain people consider this boundary between themselves and the rest of the world to be a vital part of their faith and community. “Worldliness” is a sign that the boundary is breaking down; giving in to the habits of the world is, in a real sense, giving in to evil. Many elements of Amish culture that outsiders find so outmoded are symbols of that separation and help make the boundaries between the Amish and non-Amish worlds unmistakably clear. Thus the use of horse-and-buggy transportation, the wearing of bonnets and beards, the houses with no electricity from public power lines—all are tangible indicators that the Amish are different from their neighbors. In some cases, of course, the differences are more than symbolic: Old Order choices also fundamentally shape life in important ways. But symbolic or substantive, Old Order separation from the world is real.

An Amish woman shopping at a Wal-Mart Super Center near Goshen loads her purchases into a cargo van driven by a non-Amish driver who brought her to town. Cash income from nonfarm occupations and the presence of suburban retail stores has changed some Amish purchasing patterns in this relatively progressive Amish settlement.

PHOTO BY JOEL FATH.

The Amish are keenly aware of this distinction between “the world,” which includes a great deal of evil, and the church and all that is good. They accept literally the biblical injunction of Romans 12:2 that Christians should conform, not to the standards of this world, but to a higher calling of God. Part of that calling is commitment to a community of believers—the royal priesthood mentioned in 1 Peter 2:9 or the “peculiar people” cited in Titus 1:11–14.

In contrast, the Amish generally use “the world” to describe everyone and everything that stands apart from their under-standing of the gospel. For example, to be “worldly” is to live a way of life that follows the latest fashions, aspires toward professionalism, becomes computer literate, spends a lot of money and time on leisure activities, and assumes that televisions and DVD players are necessities.

The Amish settlement just east of Paoli is remarkably conservative, and houses are notably austere inside and out. Here windmills are still the means of drawing water, and homes have none of the landscaping or patio decks that might be found in more progressive settlements.

PHOTO BY THOMAS J. MEYERS.

It is particularly important to the Amish that the boundary between church and state is clear. Although they believe that a corrupt world requires human government, including a military and a police force to provide order, the Amish avoid involvement in anything that places them in direct contact with government. They refuse participation in the military, and most do not accept Social Security payments or other forms of government subsidy.

The Church as Regulator and Sustainer

The Old Order Amish church wields a great deal of influence over individual members, but along with limited personal freedom comes the joyful support and security of the church community. Joining the church requires submission to authority. Every local congregation—or “church district,” as the Amish call them—has its own Ordnung, or set of prescribed guidelines for living. Yielding to the Ordnung is understood to be acting like Christ, who willingly submitted to the will of God, even to the ...