- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"An innovative and original study that sheds light on masculinity, youth culture, performative violence, and the circuit of global imagery." —Stephan F. Miescher, author of

Making Men in Ghana

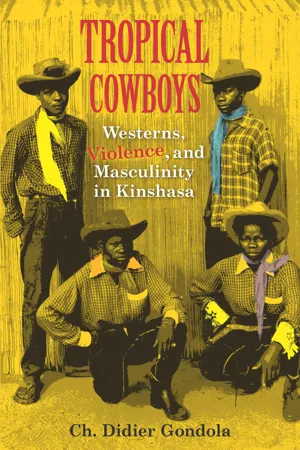

During the 1950s and 60s in the Congo city of Kinshasa, there emerged young urban male gangs known as "Bills" or "Yankees." Modeling themselves on the images of the iconic American cowboy from Hollywood film, the Bills sought to negotiate lives lived under oppressive economic, social, and political conditions. They developed their own style, subculture, and slang and as Ch. Didier Gondola shows, engaged in a quest for manhood through bodybuilding, marijuana, violent sexual behavior, and other transgressive acts. Gondola argues that this street culture became a backdrop for Congo-Zaire's emergence as an independent nation and continues to exert powerful influence on the country's urban youth culture today.

"Aligns social banditry with popular cultural formations and subcultures. This has been a longstanding feature of Didier Gondola's scholarship that is of great interest." —Peter J. Bloom, University of California, Santa Barbara

"Its approach in terms of poverty and unemployment combined with a subtle interest in performance and the creation of an original culture makes this book an eye-opener. Both the dramatic subject and the author's vivid style make it a pleasure to read and also food for thought regarding issues that haunt not only Africa but also the world at large." — American Historical Review

During the 1950s and 60s in the Congo city of Kinshasa, there emerged young urban male gangs known as "Bills" or "Yankees." Modeling themselves on the images of the iconic American cowboy from Hollywood film, the Bills sought to negotiate lives lived under oppressive economic, social, and political conditions. They developed their own style, subculture, and slang and as Ch. Didier Gondola shows, engaged in a quest for manhood through bodybuilding, marijuana, violent sexual behavior, and other transgressive acts. Gondola argues that this street culture became a backdrop for Congo-Zaire's emergence as an independent nation and continues to exert powerful influence on the country's urban youth culture today.

"Aligns social banditry with popular cultural formations and subcultures. This has been a longstanding feature of Didier Gondola's scholarship that is of great interest." —Peter J. Bloom, University of California, Santa Barbara

"Its approach in terms of poverty and unemployment combined with a subtle interest in performance and the creation of an original culture makes this book an eye-opener. Both the dramatic subject and the author's vivid style make it a pleasure to read and also food for thought regarding issues that haunt not only Africa but also the world at large." — American Historical Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tropical Cowboys by Ch. Didier Gondola in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Afrikanische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FALLING MEN

1 “Big Men”

In every age, not just our own, manhood was something that had to be won.

Leonard Kriegel (cited by Gilmore 1990: 19)

THE PURPOSE of this chapter is to follow the threads of manhood and violence back in time—to when Kinshasa, and more generally the area around the lakelike expansion of the Congo River now known as Malebo Pool, displayed different geographic and social configurations—and to draw some parallels with the changes that would occur later, during colonization. The fact that manhood has been a constant quest in all human societies, if a difficult and precarious one, is something that is now well established. In all societies, boys are meant to become men, yet the meaning of becoming and being men varies considerably from one society to another. Thus, to borrow from Michael Kimmel (1996: 5), “manhood means different things at different times to different people.” Even within the same society, the ways in which manhood and masculinity are constructed tend to vary as social, cultural, and economic changes unfold. Yet those differences and variations should not obfuscate the fact that some patterns remain the same.

In other words, it is quite conceivable that similar cultural notions may inform constructions of manhood over several generations. That is to say that young men may keep fragments from past experiences in each generation to reorder the puzzle that they have inherited from their immediate forebears. Indeed, using cipher, puzzle, and enigma as metaphors for unresolved gender identity (see Gilmore 1990: 5) is an astute way to capture its vexing and labile nature. It tells us something that we have known for some time: that we know little about how men and women form their gender identity, how they pick up pieces from a variety of sources so as to arrange and rearrange an unresolved puzzle. Before showing in coming chapters how young people in Kinshasa harnessed global images, most notably from Hollywood renditions of the American Far West, to construct both manhood and masculinity, here and in the next chapter, local sources, fragments, and experiences will be examined.

When the so-called Bills (named after Buffalo Bill, aka William Frederick Cody, the Bills’ eponymous hero) or Yankees emerged in Kinshasa’s townships in the late 1940s, various standards of masculinity competed for their attention. They did not have to look far, however, to figure out how manly society expected them to behave. Colonization in the Belgian Congo had morphed from a brutal venture based mostly on economic predation into a regimented and engineered process of social Darwinism. Like their fathers, most of whom were rural natives who had moved (or moved back) to Kinshasa following the end of the Great Depression and the beginning of World War II, the Bills chafed under a system in which manhood indeed had to be won. How daunting it must have been for these youths to become men in a colonial context and against a colonial ideology that essentialized Congolese man as a child or, worse, as the infamous Hegelian animal-man. Unless they accepted European tutelage, with all its paternalism and racism, African males could meet humiliating and emasculating treatment in the workplace and elsewhere in the colonial city. This may explain why Congolese youths eschewed the Belgian version of the Victorian male that missionaries, among others, tried to enforce in the townships and why some attributes of manhood that had been dominant in precolonial Malebo Pool beckoned so forcefully in the ways in which they constructed their manhood in 1950s Kinshasa.

Most works to date that explore precolonial societies in the Congo Basin rarely discuss manhood and masculinity as epistemological categories. Men loom so large and the focus on men is so sharp in these works that manhood and masculinity tend to disappear or, when they do appear, to seem like a collection of ungendered categories. Even later studies (Vansina 1973; Obenga 1976; Harms 1981) only make tangential references to these central issues and hardly concern themselves with the quintessential question of what it meant then to be a man. We know, for instance, that men monopolized social, political, and economic resources in precolonial Congo and that gravitation toward wealth and power (which were essentially one and the same) constituted the sure path from boyhood to manhood and drew a clear line between maleness and its gendered opposite. We also know that the ability to deploy and display oratory skills, using sometimes esoteric proverbs, qualified one for manhood. What these studies never discuss, however, is how much of this was constructed, negotiated, and privately and publicly performed; how the archetypal precolonial male at once revealed and obscured other forms of manliness; and, finally, how manhood perpetuated itself through rituals, enactment, and performances. It is, of course, beyond the scope of this work to redress this. Yet there exists a filiation between (1) manhood performances that can be surmised from works published on pre-colonial Congo and (2) patterns of manhood and masculinity that Kinshasa’s youth exhibited in the late colonial period. This filiation, or line of descent, will become much clearer in later chapters.

The “Great Congo Commerce”

The area where Kinshasa sprawled in the 1930s was first settled by Tio (or Teke) traders, who had such a ruthless grip over regional trade that, according to French explorer Léon Guiral (1889: 254), their partners came to resent them as Congo ruffians (écumeurs du Congo). Sporadically, Bobangi traders and ivory carvers would also settle there. When Henry Morton Stanley arrived in February 1877, he did not fail to describe in his travelogues (1879: 327) the hustle and bustle of Nshasa1(Kinshasa), Nkounda, and Ntamo (Kintambo). Under Tio lords and big men, all three settlements witnessed the traffic of Zombo and Kongo traders, who came as far as the Loango coast to trade salt, cloth, secondhand European clothes, pottery, glassware, copper, guns, and gunpowder in exchange for ivory and slaves, which according to Jan Vansina (1990: 200) were not traded in Malebo Pool until the Portuguese appeared on the Kongo coast. Following Guiral’s apt characterization, Vansina (1973: 248) has convincingly argued that the magnitude of the trade the Tio and their partners carried out in Malebo Pool warrants the term “Great Congo Commerce.” Many fishing villages along the Congo River became trading centers, as people of the central Congo Basin sought to “benefit indirectly from international trade by using it to promote regional trade” (Harms 1981: 5).

Prior to the arrival of Stanley, a few important changes had occurred in Tio society which increasingly reinforced trade as the main activity in the area. For example, the Tio, like many other groups in Equatorial Africa, had abandoned the cultivation of maize for manioc, a New World plant that the Portuguese had introduced in the sixteenth century. According to Vansina, they also had foregone iron smelting, pottery making, and raffia-cloth weaving and depended mostly on imports from the coast (Vansina 1965: 81; see also Dupré 1982).

Kinshasa’s central and convenient location had much to do with its importance as a nodal center of trade. This is where the powerful Congo River stretches into Malebo Pool—its last navigable expanse, which covers nearly 300 square miles, with 14-mile-long Mbamu Island in the middle—before rushing to the sea in a succession of thirty-two cataracts and several falls and rapids. From this point on, any travel to the coast had to be managed by human porters, both because animals in this tropical area were prone to trypanosomiasis and because transporting canoes overland, to bypass the cataracts, was a titanic task. The presence of this chokepoint forced traders coming from the upper Congo area to make a stop in Malebo Pool and trade. It also transformed the Pool into an important demographic hub that sustained at least 30,000 people on the south bank alone, according to Léon de Saint-Moulin’s (1976: 464) estimate.2 In addition to Tio permanent residents, the area saw temporary settlements of Bayanzi, Bobangi, Aban-Ho, and Bafourou, settlements that waxed and waned following periods of trading boom and bust.

It did not take long for Stanley to realize that if Leopold II of Belgium were to take control of the Congo Basin, the center of his colonial domain would have to be Malebo Pool (which Stanley originally named Stanley Pool, after himself). To make space for the new European settlement, the first colonial authority adopted a repressive policy that systematically drove the Tio residents out of their hubs in the Pool. In 1891, the Teke chief Ngaliema—whom Camille-Aimé Coquilhat (1888: 61) sardonically referred to as an “intruder” into a space that Europeans claimed the exclusive right to occupy—also had to make room for the newcomers and seek refuge across the Pool, in French-occupied Congo, after his village of Ntamo (or Kintamo/Kintambo) was ransacked and looted by colonial troops. A few years earlier, in 1888, the village of Lemba, which belonged to the Bahumbu, had been set on fire after its inhabitants refused to allow African laborers to cut down trees on their communal land for the construction of the new European post.

A similar fate met the village of Nshasa (or Kinshasa), which was perhaps the largest precolonial settlement on the south bank of the Pool (Gondola 1997a: 53). Its Bateke residents were forced to resettle farther upriver, near another Bateke village, Kingabwa, which in turn had to relocate toward Ndolo. By 1911, when the European settlement was permanently established where the village of Kinshasa had once stood, all the African villages either had been pushed farther up the Congo River or had moved across the Pool to the French-occupied Brazzaville area.

Lords and Big Men

The colonial onslaught upset a system that revolved around social endowment accumulated by lords and big men who held sway in the villages that dotted both banks of the Pool. There is no doubt that Ngaliema, who asserted his authority in Kintambo, acted as a power broker when Stanley set foot in the area. But he was by no means the only lord in this vast and coveted area, where the economic stakes were simply too high for a single man to cash in on the lucrative commercial flows that washed ashore of the Pool. In fact, Malebo Pool enjoyed a polycephalous political system, with several chiefs positioned at key economic nexuses, asserting their authority thanks to a combination of military might and mystical power. This was certainly the situation when the first European visitors arrived in the area.

Each village had its hereditary lord who acted on behalf of the community and represented its best interests in an environment rife with feuds and conflicts over land, trade, and prestige. The lord was assisted by several big men whom he might use as a collective body, a council, and a sounding board for important decision making affecting the village or simply as right-hand men and trusted advisers. These were usually kinsmen whom the lord would dispatch to other villages to negotiate deals and report back to him. When the matter required the presence of the lord himself, he was always accompanied by a retinue of big men.

At one such meeting, when Ngaliema paid a visit to Stanley to greet him on his second trip to the Pool, he was “accompanied by several chiefs of Ntamo; such as Makabi, Mubi, old Ngako, and four others” (Stanley 1885: 306). As in any feudal structure, in exchange for their services and loyalty, the lord provided protection to his chiefs and big men and administered justice in his entire realm. We should let Stanley describe a few of them:

Old Ngako is garrulous and amusing, and requires but little prompting to spin out tales of adventure and war. The ancient fifer of Ngalyema [Ngaliema], who lives recluse-like in his lone hamlet halfway between Léopoldville and Kintamo, is a chatty, agreeable old man, and is by no means churlishly inclined. Makabi is a character also deserving closer study; he is an acute fellow, neat in person, fully possessed of the authority of a chief, and lord over a large number of pretty wives and bright-eyed children. Even Ngalyema himself at home is a better man than Ngalyema abroad; he has a miscellaneous treasure which he has no objection to show; he will tell you with equanimity of what will happen when he is dead; how he will be swathed in cottons and woollens and silks and satins, and, after many days of continued fusilading, will be buried in an honoured grave. (Stanley 1885: 391)

Stanley had initially misread the power dynamics in Malebo Pool after learning that Makoko, lord of Mbé, had ceded a huge territory to his French rival Savorgnan de Brazza. After inquiring of Gamankono, one of the rare big men who won his praise, Stanley was told by him:

There is no great king anywhere. We are all kings—each a king over his own village and land. Makoko is chief of Mbé; I am chief of Malima; Ingya is chief of Mfwa; Ganchu is chief over his land. On the other side, Gambiele is chief of Kimpoko; Nchuvila is the great chief of Kinshassa. But no one has authority over another chief. Each of us owns his own lands. Makoko is an old chief; he is richer than any of us; he has more men and guns, but his country is Mbé. (Stanley 1885: 298)

Thus although Makoko seemed able to keep all the chiefs and big men in check on the north bank of Malebo Pool, in a huge area strongly secured by the central position of Mbe, the capital of his fiefdom, on the south bank of the Pool it was indeed Ngaliema who, according to Stanley, acted as “the umpire and referee in all disputes among minor chiefs between Kinsendé Ferry and Kintamo” (323). Stanley even called him “the supreme lord of Ntamo” (307).

Ngaliema’s prestige rested on the wealth he had accumulated as a shrewd trader who used both flair and the threat of war to get what he wanted. Ngaliema and other Teke chiefs basked in such lucre, surfeited as they were with so much fine cloth and other imported goods, wrote W. Holman Bentley (1900, 2:19), that they could afford to keep their wives in laziness. From being a slave, Ngaliema had risen to considerable status and wealth. His compound in Kintambo was rumored to boast the largest collection of elephant tusks at the Pool, with some individual tusks weighing nearly 100 pounds, according to both Stanley and Coquilhat. He also had “piles of silk, velvet, rugs, bales of blanket cloth, glass ware, crockery, gunpowder, and stacks of brass rods, etc.” (Stanley 1885: 311).

Lords and big men flaunted their wealth on certain occasions when a level of decorum and pomp was expected. Here is Stanley describing a precursor of the sartorial ostentation that was to become the hallmark of all youth movements on both sides of the Pool since at least the 1920s:3

Ngalyema and his chiefs were dressed splendidly this day. It was probably a visit of state. Each chief was dressed with a flowing silk robe, under-vest of silk, cotton underclothes, with an outer dress of silk; yellow, blue and crimson seemed to be the favourite colours. Ngalyema’s arms were almost completely covered with polished brass rings, over which were heavy brass wristlets and armlets. His ankles were adorned with red copper rings, which must have weighed 10 lbs. each. Makabi was similarly dressed, for he seemed to be a rival in dress and equipments. The other chiefs exhibited their individual tastes. (Stanley 1885: 364)

In a social environment where land ownership did not exist, men acquired status through personal qualities such as bravery, eloquence, and seniority, yet nothing could top the acquisition of goods, wives, and slaves. Lords and chiefs such as Makoko and Ngaliema distinguished themselves by the possession of staggering numbers of slaves and wives and the latest and fanciest wares from Europe that came from the coast during the dry season in the caravans of Kongo and Zombo traders. They lived in a cluster of houses that formed a courtyard built inside a palisade, so as to accommodate the wives, slaves, and clients who easily integrated into their extended families (Vansina 1973: 73).

Lords and big men also had exclusive access to stockpiles of imported guns and gunpowder that they used primarily as a deterrent to potential challengers, including Europeans. On his second journey to the Pool, in 1881, after four years of absence, St...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. Falling Men

- Part II. Man Up!

- Part III. Metamorphoses

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index