![]()

PART 1

THE MAKING OF A SULTAN

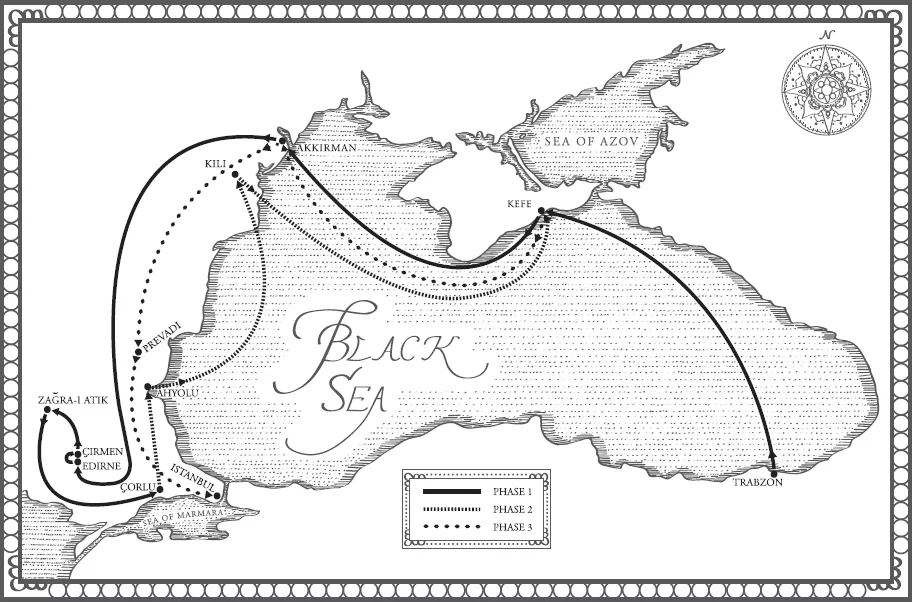

Map 1.1. Selīm’s Itinerary during the Succession Struggle. Phase 1: From the Princely Governorate of Trabzon to the Battle of Çorlu (October 1510 – July 1511); Phase 2: Escape from Çorlu to Kefe (August 1511); Phase 3: From Kefe to the Throne (April 1512). Map by Rachel Trudell-Jones.

![]()

1 Politics of Succession: Selīm’s Path to the Throne

Muradiye, sabrın acı meyvası1

OTTOMAN SUCCESSION practices have been aptly labeled “succession of the fittest.”2 The terms the Ottomans used to denote successor (ḫalef), conflict (iḫtilāf), and opposition (muḫālefet) share a common Arabic root, indicating that they were certainly conscious of the inherent potential for crisis that all successions represent.3 The Darwinian nature of their succession practices was further accentuated by the fact that no ascriptive or routine principle regulated succession to the Ottoman throne on anything more than a temporary basis until the codification of primogeniture in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.4 Hence, Anthony Dolphin Alderson’s frank assessment is apt: “Far from there being any theory of primogeniture … the law of succession may well be described as a ‘free-for-all,’ in which the strongest of the sons inherited the throne, while the others … suffered death.”5

The absence of a predetermined system of imperial succession did not mean that the Ottoman practice of dynastic succession was haphazard. On the contrary, the Ottomans followed certain principles, some upheld by earlier Turco-Mongolian polities, in an exceptionally deliberate fashion. First, in accordance with the premodern Turco-Mongolian political tradition, the entire imperial territory was considered the patrimony of the dynastic family. Second, each and every male member of the House of ʿOs̱mān was considered the beneficiary of divine grace and therefore was theoretically eligible, and equally legitimate, to rule.6 This was why, as Halil İnalcık notes, earlier Turkish rulers of tribal empires in Central Asia attributed their sovereignty to a sacred source of authority and their own personal fortune (ḳut).7 Within the Ottoman context, this notion of personal fortune, along with its connotations of innate charisma and divine mandate to rule, corresponded to the concept of devlet.8 The intricate correlation between possessing personal fortune and attaining the sultanate was signified semantically as well; the word “state” in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish evolved from the Arabic word dawla, the connotations of which include “change or turn of fortune.”9 Third, that all male members of the House of ʿOs̱mān possessed innate charisma and personal fortune did not mean that they possessed them equally. Rather, the Ottoman practice of battling for succession was based on the assumption that at any given time only one male member of the dynasty was invested with the divine mandate to rule the entire imperial realm.

Within a political-theoretical framework restricted by these parameters, the Ottomans persistently pursued a competitive form of a succession practice that Cemal Kafadar has called “unigeniture.”10 Competitive unigeniture was essentially a zero-sum game and entailed a contentious process by which one of the deceased sovereign’s male relatives eliminated all other rival pretenders for the throne in order to assume control of the entire empire.11 Although the Ottomans practiced it consistently ab initio, unigeniture was systematized as a method of succession only when Meḥmed II declared in his code of law (ḳānūnnāme) that “it is appropriate for whichever of my sons attains the sultanate with divine assistance to kill his brothers for the sake of the world order (niẓām-ı ʿālem).”12 The destructive nature of competitive unigeniture was experienced both before and after the codification of fratricide, as evidenced by the fatal competitions of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries between the sons of Bāyezīd I, Meḥmed II, Bāyezīd II, and Süleymān I.13 In 1574, when Murād III acceded to the throne, he executed all five of his younger brothers; in 1595, his son Meḥmed III, on his own accession, executed nineteen.14

The devastating effects of fratricidal wars notwithstanding, the practice of unigeniture in the form of “succession by combat”—by which the Ottoman monarch was principally defined as a conqueror—fell perfectly in line with the fundamental ideology of an expansionist military polity.15 Despite the Ottomans’ strict adherence to unigeniture, their succession practices were akin to those of other, earlier Turco-Mongolian polities of the steppes. As Joseph Fletcher argues, the Ottomans were also sedentary heirs to the Inner Asian tribal custom called “tanistry,” which prescribed, usually via murder or war, the transition of supreme rule of the empire to the most competent member of the ruling family.16 To ensure the enthronement of the most suitable candidate, the Ottomans practiced both customs; in this context, unigeniture enabled them to successfully combine an overarching and time-honored Turco-Mongolian tribal principle with their aversion to a predetermined system of imperial succession and with a special emphasis on fortune (devlet). Thus, until the introduction in the seventeenth century of a preference for seniority, battles for succession were waged—both literally and figuratively—as battles of fortune.17

In an effort to prove that he indeed possessed the exclusive divine mandate to rule, each claimant to the Ottoman throne had to demonstrate that his fortune was superior to the fortunes of his rivals. This competitive endeavor was such an integral part of Ottoman political culture that there existed an idiomatic expression to denote the mutual testing of fortune (devlet ṣınaşmak).18 The ultimate proof of an individual’s fortune was embodied in his success on the battlefield. When it came to Ottoman successions, nothing succeeded like success, which was recognized as the ultimate expression of divine favor, emanating from the same sacred source as charismatic authority.19 That was why, per Halil İnalcık, “when Bāyezīd II and Selīm, Süleymān the Lawgiver and Muṣṭafā confronted each other in battle, they believed that they were subject not to their own will, but to the will of an incorporeal power, the will of God and the state.” It is for these reasons that, in large part, they accepted the outcome of dynastic struggles by entrusting their fates to God (tevekkül).20

Bāyezīd II’s fate was to die under suspicious circumstances on the way to his mandatory retirement in Dimetoka (Didymotichon, Greece); Selīm’s fate was to rule the Empire as its ninth sultan. One cannot help but wonder whether the deposed sultan indeed accepted this unfortunate turn of events as divine judgment. There is absolutely no doubt, however, that each of the claimants to Bāyezīd’s throne worked diligently to manipulate God’s will by securing the political and military assistance of various factions at the imperial capital and in the provinces of the Empire. There is also no doubt that among Bāyezīd’s princes, Selīm was the most successful at this manipulation.

Based on a wide array of (primarily Ottoman) archival and narrative sources, this chapter addresses the rise to power of Selīm I. It traces the complicated trajectories of four dynastic protagonists and examines the shifting loyalties of the military and political factions that supported them, thus building a coherent story of—and a meaningful frame of reference for—the events that culminated in Selīm’s accession to the Ottoman throne on April 24, 1512. Bāyezīd II, the legitimate ruling sultan at the time, and his sons, Princes Aḥmed, Ḳorḳud, and Selīm, are the principal actors in this political drama.

Whereas the later chapters of this book focus on the historiography on Selīm I and the posthumous construction of his image, the present discussion is strictly historical in nature. It draws from sources that include but are not limited to imperial decrees (ḥükm), letters (mektūb, kāġıd), petitions (ʿarż), spy reports, copybooks of correspondence (münşeʾāt), general histories of the Ottoman dynasty (tevārīḫ-i āl-i ʿOs̱mān) by known and anonymous authors, a corpus of literary-historical narratives commonly referred to as Selīmnāmes (Vitas of Selīm), and, last but not least, Venetian relazioni. The précis of events provided in the following pages is based on these textual sources, whose authors display a variety of attitudes and agendas.21

Succession Politics: The Provincial Factor

Let us begin at the very beginning. Bāyezīd II had eight sons, five of whom preceded him to the grave.22 With the notion of unigeniture dictating Ottoman succession practices since the inception of the polity and with the competitive nature of that concept, which was explicitly revealed by Meḥmed II’s codification of fratricide in the last quarter of the fifteenth century, the stage for the struggle between Bāyezīd’s remaining sons was set long before violence erupted in 1511.23 Because securing the imperial capital on the death of an Ottoman ruler was of paramount importance for contenders to the throne, the dissension between Bāyezīd’s princes manifested initially as an incessant struggle over the provinces; each contender sought to outmaneuver his rivals by scoring a gubernatorial appointment to the province nearest to Istanbul. With gubernatorial seats in the Balkan provinces denied to Ottoman princes since the civil war following the Battle of Ankara in 1402, this struggle was initially confined to Anatolia.24

Ḳorḳud’s career as governor (sancaḳ begi), for example, began with an appointment to the western province of Saruhan in 1491.25 After Bāyezīd II denied his request to be posted in the northwestern town of Bergama, in 1502 Ḳorḳud was appointed to the southwestern province of Teke, with the province of Hamid added to his domain in 1503.26 Although this appendage more than doubled Ḳorḳud’s annual income, there was little doubt that the prince was being kept at arm’s length from the seat of imperial power. A few years later, Ḳorḳud had a falling-out with grand vizier Ḫādım ʿAlī Pasha (d. 1511), the most prominent supporter of his older brother Aḥmed, over hunting grounds (şikāristān) and ports (iskele, līmān) located within the borders of his province.27 This appears to have been the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back; on May 18, 1509, shortly after his disagreement with the grand vizier, Ḳorḳud sailed to Egypt.28 Having failed to secure the military support of the Mamluk ruler Qānṣūh al-Ghawrī (r. 1501–1516) in his quest for the Ottoman throne, however, Ḳorḳud had no choice but request to be reinstated to his former governorate.29 Ḳorḳud’s letters of apology, addressed to Bāyezīd II and Ḫādım ʿAlī Pasha—as well as a treatise he composed to explain that he came to Egypt not to defy his father’s orders but to go to Mecca to perform the pilgrimage—apparently had the desired effect.30 Once back in the Ottoman realm, however, Ḳorḳud resumed his bid for an appointment closer to Istanbul, petitioning to be transferred to the province of Aydın.31 Judging by the desperate tone of a letter he sent to his sister in 1511, Ḳorḳud’s request fell on deaf ears. In this letter, he complains of being treated as an outcast, left to suffer in his current province.32 Moreover, inaccurate intelligence concerning his father’s decision to grant Manisa to his rival brother Selīm appears to have increased Ḳorḳud’s desperation. Anxious to overtake his adversary, Ḳorḳud left his province and set out for Manisa.33 The consequences of Ḳorḳud’s choice to leave his gubernatorial seat were more momentous than he could have anticipated; to no small extent, it sparked the Safavid-instigated Şāhḳulu rebellion the same year.

Conversely, Ḳorḳud’s older brother Aḥmed had been appointed to the prestigious province of Amasya in 1481, as soon as his father had ascended to the Ottoman throne. He was not, however, absolutely free of anxiety. Although his brothers governed distant provinces, Aḥmed became increasingly concerned about keeping his path to the imperial capital clear as Bāyezīd II’s days were coming to a close. Thus, he kept a vigilant eye on Ḳorḳud’s movements in western Anatolia and also observed Selīm’s activities closely, intervening immediately in 150...