![]()

NONPROFIT STRUCTURES FOR THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

![]()

SEVEN

Science, Professionalism, Foundations, Federations

Large, national, secular nonprofit organizations assumed a prominent place in the American nonprofit world early in the twentieth century. Between 1900 and 1920 a highly influential group of foundations, research universities, and social service federations—all of which espoused a nonsectar-ian and “scientific” outlook—appeared on the American scene. Nineteenth-century nonprofits, which continued to operate, were small, even domestic in scale, and were closely associated with religious groups. Even the larger private colleges, hospitals, and museums that had accumulated substantial physical assets were still governed by self-contained boards whose members shared clearly defined religious and cultural outlooks. Many of the American communities that nonprofits served, however, had become large and diverse. In 1900 the five boroughs of New York City contained well over 3 million people; Chicago’s population had passed 1.5 million, Philadelphia’s, 1 million; and many communities had more than 250,000. After 1900, moreover, medicine and other professions that persuasively advanced the claims of science gained overwhelming prestige in the provision of most health care, educational, and even human services. Small, sectarian organizations could not excel in the new environment.

Municipal and county governments and local school districts had always provided most of the funds needed for elementary education and for the care of the poor, the elderly, and the sick. That pattern continued into the twentieth century, as local and state governments accepted responsibility for new services ranging from sanitary water and sewer systems to high schools and expanded state colleges. After 1900, however, the very large foundations that Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and others created out of their industrial wealth played a key role in the transition to large-scale scientific institutions. Applying to their giving the systematic, methodical thinking that had helped them gain vast fortunes, Carnegie and Rockefeller articulated explicit philosophies of giving, philosophies that emphasized what Rockefeller called a “wholesale,” broad and institution-shaping approach, rather than “retail” giving to individuals and small agencies. Early managers of the national foundations played key parts in the development of the national policy “think tank,” city planning, social work, public health, the modern medical school, the research university, standardized college admissions tests, the high school curriculum for “college-bound” students. Where European and Asian nations used national governments to develop similar institutions and standards, as historians Stanley N. Katz and Barry D. Karl have shown, the highly decentralized government of the United States left the field to new, national, nonsectarian, foundations that celebrated “objective” science.

American nonprofits also transformed their relationships with small donors and with those who pay for their services: in effect, they applied the principles of mass marketing to the field. By the beginning of the twentieth century fundraisers had learned that narrowly defined Protestant evangelical causes did not appeal to the rapidly increasing numbers of potential donors in the great industrial cities who were devout Catholics or who belonged to other religious traditions. Nonprofit leaders responded with the nonsectarian federation, the “community chest,” and the community foundation, first in Cleveland by 1914, then throughout the midwest, much of the northeast, and the far west. In another break with the religious, amateur, voluntary basis of so many nineteenth-century nonprofits, the new nonsectarian federations emphasized their commitment to the provision of service—medical care, education, job training, family counseling—by highly educated professionals, at the highest possible up-to-date, scientifically determined, national standard.

The new federations succeeded, with the critical assistance of corporate payroll offices, in attracting significant new flows of funds for their member agencies. The first federations were local community chests, but their new formula had national implications, as the March of Dimes demonstrated in the 1930s and 1940s. The hospital officials who created what became the Blue Cross movement (also in the midwest) during the same years applied a similar formula as they successfully sought to persuade ordinary salary- and wage-earners to “prepay” for hospital care. Together, the new national foundations and the largely local federations seemed, during the 1920s, to bring corporate leaders and ordinary citizens together into what historian Ellis Hawley has described as the “Associational State,” a national government based on voluntary cooperation among private interests.

National foundations and nonsectarian federations helped to transform health care, human services, and higher education—and indeed the entire nonprofit sector—in the first third of the twentieth century. They emphasized scientific progress, efficiency, and universality, but they did not please everyone. Deeply committed evangelical Protestants (and, less prominently, some Catholic and Jewish leaders as well) objected to the abandonment of a religious basis for human service. Labor leaders objected that the massive exploitation of workers, not the genius of a few industrialists, created the fortunes that made possible the great foundations: hence, they insisted, any power assumed by foundation leaders was illegitimate. More profoundly but less noted at the time was the fact that where women had played central roles in the religiously based human service and health care nonprofits of the nineteenth century, men dominated the new enterprises of science and professionalism from the 1920s through the 1970s.

![]()

31

Debate over Government Subsidies: Amos G. Warner, Argument against Public Subsidies to Private Charities, 1908; Everett P. Wheeler, The Unofficial Government of Cities, 1900

Amos G. Warner’s American Charities went through many editions, serving for nearly 50 years as the essential text on charities and their administration in the United States. In editions published around the turn of the century Warner included an extensive description and critique of the widespread practice by which municipal (and county) governments provided funds to private orphanages and other charitable institutions, most of which were sponsored by religious bodies. In his critique, Warner explicitly rejected the arguments in favor of public support for private agencies advanced by Everett P. Wheeler.

Warner designed his account of public subsidies to private charitable agencies not in the spirit of impartial research, but as part of his powerful argument against such subsidies. Although his account is very extensive, it is not a complete description of the subsidies that nineteenth and early twentieth-century governments provided to private agencies. In particular, Warner failed to discuss the important role of county subsidies, of food and fuel as well as building and operating funds, to orphanages, hospitals, sanitoria, and homes for the elderly.

Warner sought above all to persuade his readers that public funds should not go to private agencies. He asserted that only governments—preferably state governments—were sufficiently powerful and accountable to create comprehensive, effective, fair, efficient, up-to-date services. He made five main arguments against government subsidies to private agencies:

Because private institutions provide care that the public views as better and more respectable than the care offered by public asylums, irresponsible parents and children are more likely to place their dependents in private institutions. Thus public subsidies “promote pauperism by disguising it.”

Because virtually all private institutions are sponsored by religious groups, subsidies to charities are necessarily subsidies to religion, in violation of the First Amendment and of good political sense: moreover, any democratic government that subsidizes one religious agency must subsidize many others, so that the multiplication of agencies and the inefficient duplication of services is the inevitable result. Moreover, a government that provides public subsidies to private charities sets a precedent for public subsidies to private and parochial schools.

Private agencies pull resources from and thus displace efficient, comprehensive public systems of social care.

Because private agencies are sponsored by religious groups, legislators cannot exercise their critical judgement in voting on subsidies. Once established, public subsidies introduce religious issues into politics, create powerful vested interests, and make it difficult to achieve political or programmatic reform.

Public subsidies displace private benevolence; public subsidies allow charitable agencies to become dependent on and deferential to the government officals who control the flow of funds, thus encouraging agency managers to distort programs to maximize subsidy payments.

A New York City lawyer and civic leader who often represented Catholic institutions, Everett P. Wheeler offered a remarkable overview of the role of nonprofit organizations in his city at the beginning of the twentieth century in this article published in the Atlantic Monthly.

Wheeler began with a reference to the contemporary movement to reform city governments in the United States. In fact, he pointed out, Americans were already working to solve many problems through the “unofficial governments” of nonprofit organizations. “Private corporations, chartered by the legislature, but receiving no pecuniary aid from the state, do in fact discharge a very considerable and important part of the functions which by charter are devolved upon officials,” Wheeler wrote. His examples included the vigilantes who provided private police services (of a fashion) in early San Francisco, as well as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals; its successor, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children; and Anthony Comstock’s anti-birth control, anti-abortion Society for the Suppression of Vice.

Wheeler acknowledged in passing that these law enforcement societies did in fact receive public support, in the form of rent-free office space in courthouses. Orphanages, of course, received very significant funds from state and municipal governments. Wheeler’s defense of municipal subsidies for such charities was perhaps his strongest motivation for writing this striking essay on nonprofits as a sort of “unofficial government” for American cities.

AMOS G. WARNER

Argument against Public Subsidies to Private Charities

1908

When contributions are hard to get, when fairs and balls no longer net large sums, and when endowments are slow to come, the managers of private charities frequently turn to the public authorities and ask for a contribution from the public revenues. On the other hand, when State legislatures see the annual appropriation bills increasing too rapidly, and when they see existing public institutions made political spoils, and the administration wasteful and inefficient, they are apt to approve of giving a subsidy to some private institution, instead of providing for more public buildings and more public officials.

This problem of granting or of not granting public subsidies to private charitable corporations is analogous to the problem of public versus sectarian schools on the one hand, and of governmental control of private business corporations on the other—allied to both but identical with neither. It is related to the school question not only because the care of dependent and delinquent children by sectarian institutions involves their education in the faith of a particular sect, but because there is reason to believe that the subsidizing of sectarian charities has been resorted to with the conscious purpose of evading the laws that forbid public aid to sectarian schools. It is related to the problem of governmental control of private corporations not only by the fact that the legal questions involved are frequently the same, but by the fact that the methods used by eleemosynary corporations to secure public subsidies are often not unlike those used by money-making corporations to secure legislative favors.

The States most largely committed to the subsidy or contract system are shown in Table 1. It is seen from this table that Pennsylvania, New York, California, and the District of Columbia give the largest amounts in subsidies to private charitable institutions. A review of the facts regarding State aid in these localities will serve as a basis for the discussion of the advantages and dangers of the system.

Table 1:

Subsidies to Private Charities, 1901*

| States Granting Largest Amounts | State Subsidies Granted | Other State Aid | Local Subsidies Granted | Other Local Aid, Amount Not Reported |

| Vermont | $54,000 | | $2,000 | Yes |

| Connecticut | 101,750 | Yes | 24,500 | Probably |

| New York | 235,000 | | 3,410,000 | |

| Pennsylvania | 6,700,000 | | 153,500 | Large |

| Maryland | 96,000 | | 185,000 | |

| District of Columbia | ... | | 200,000 | |

| North Carolina | 35,000 | | 6,200 | |

| California | 410,000 | | ... | Probably |

*Condensed from Fetter’s table, Am. Jour. of Soc., vol. vii., 1901, No. 8, p. 868.

On Feb. 2, 1893, while the Senate of the United States was sitting as town council for the city of Washington, a member moved to amend the appropriation bill by inserting a proviso that almshouse initiates or other paupers and destitute persons who might be a charge upon the public should be turned over to any private institution that would contract to provide for them at 10 per cent less than they were then costing the District. Senator Call, who introduced the amendment, explained that it was in lieu of one which had been rejected at the previous session of Congress, whereby he had sought to have $40,000 of public money given to the Little Sisters of the Poor, to enable them to build an addition to their Home for the Aged. He defended the original proposal on the ground that this sisterhood cared for the aged poor better and more cheaply than the almshouse, and that the existence of their institution had saved to the taxpayers of the District in the last twenty years a sum believed to be not less than $300,000. It was not a novel plea; for Congress had already appropriated, since 1874, $55,000 to aid the Home for the Aged of the Little Sisters of the Poor; and each year the District appropriation bill had included subsidies for a large number of private charitable institutions, some of them avowedly under sectarian management. How far the tendency to grant public subsidies to private charities had gone in the District of Columbia is in some sort indicated by Table 2.

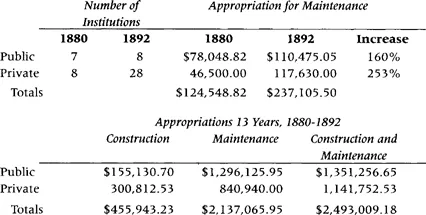

From this table it will be seen that the amount given for maintenance to private charitable institutions at the beginning of the period was a little less than one-third of the whole amount, while at the close of the period it is a little less than one-half. The most surprising fact, however, is that the District had given to private institutions nearly twice as much money to be used in acquiring real estate and erecting buildings as it had granted to its civil public institutions. Were we to deduct a sum of $66,900 charged to the workhouse, a purely correctional branch of the so-called Washington Asylum, it would appear that more than three-fourths of the money appropriated for permanent improvements in charitable institutions was given to private corporations....

Table 2

Public Subsidies to Charities in the District of Columbia 1880–1892

The tendency of public subsidies to increase rapidly—although usually granted in the first place on the ground of economy—and of subsidized charities to multiply at the expense of public institutions, is illustrated by the experience of Pennsylvania. Table 3 shows the appropriations to both classes of institutions for a period of fifty-five years.

Under the Pennsylvania system, subsidies are voted in lump sums for “maintenance” and “buildings,” but the buildings when erected do not belong to the State but to private boards on which the State is not represented. Moreover, the amounts given have no relation to the number of persons cared for, nor to the amount of private subscriptions received. Private giving is thus discouraged, and the development of private charities is determined by the subsidies obtainable rather than by the needs of the community. With charitable budgets approaching five million dollars in 1905, Pennsylvania, an old and rich State, was enlarging her accommodations for the insane with cheap, temporary one-story buildings, had no separate provision for epileptics, and no adequate provision for the feeble-minded. This neglect of State dependents is a far greater evil than the political log-rolling and favoritism which inevitably accompany the appropriation of such large sums to private interests.

The best-known and most frequently quoted example of the policy of subsidies to private charities is that of New York City. In 1894, and again in 1899, the [private, state-chartered] State Charities Aid Association made a thorough analysis of the finances of children’s institutions especially, and in 1899 made a numbe...