eBook - ePub

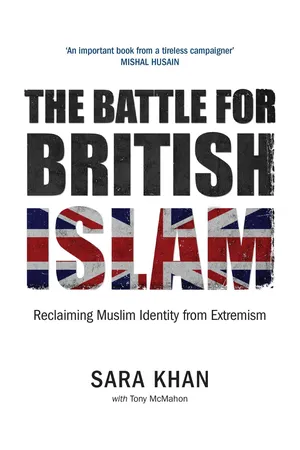

The Battle for British Islam

Reclaiming Muslim Identity from Extremism

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Across Britain, Muslims are caught up in a battle over the very nature of their faith. And extremists appear to be gaining the upper hand. Sara Khan has spent the past decade campaigning for tolerance and equal rights within Muslim communities, and is now engaged in a new struggle for justice and understanding - the urgent need to counter Islamist-inspired extremism.In this timely and courageous book, Khan shows how previously antagonistic groups of fundamentalist Muslims have joined forces, creating pressures that British society has never before encountered. What is more, identity politics and the attitudes of both the far Right and ultra-Left have combined to give the Islamists ever-increasing power to spread their message. Unafraid to tackle some of the pressing issues of our time, Sara Khan addresses the question of how to break the cycle of extremism without alienating British Muslims. She calls for all Britons to reject divisive ideologies and introduces us to those individuals who are striving to build a safer future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle for British Islam by Sara Khan,Tony McMahon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Terrorism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

RACE TO YOUR CALIPHATE: THE RISE OF ISLAMIST EXTREMISM

‘Islamic Disneyland’

Muneera told Leila that living in the ISIS caliphate would be like something she referred to as an ‘Islamic Disneyland’.1 Leila, a Muslim woman in her thirties, had been assigned to be Muneera’s intervention provider under the UK Government’s counter-terrorism programme. Her role was to provide support to individuals at risk of joining ISIS and travelling to Syria. Her charge, Muneera (whose name we have changed), was just thirteen years old.

The teenager was a third-generation British Muslim, born and raised in the UK. Her family was originally from Pakistan but had now settled in Birmingham, Britain’s second city. Her father was a mechanic in his forties, while her thirty-something mother stayed at home with the younger siblings. There was no adolescent rebelliousness with Muneera. She was very close and loving to her parents. Leila describes Muneera’s home set-up as that of a regular British Asian family.

Muneera was home-schooled but had friends in the neighbourhood and was not shy or introverted. In early 2015 her mother had become acutely ill during a sixth pregnancy and the teenager, left to her own devices, retreated to her bedroom to spend a growing amount of time online. One evening she had watched a TV news report on ISIS and logged on to her new mobile phone to find out more about this so-called caliphate in Syria and Iraq.

She began asking questions on Twitter and was excited when responses began to appear along the lines of ‘saw your tweet, tell you more about it’. A support network of seemingly like-minded people from all over the world swarmed round her on social media, telling Muneera not to trust the official media and the lies they spread about ISIS. Other girls chatted about how they were thinking of going to Syria and the great life that awaited them.

Bit by bit, Muneera formed a very strong friendship triangle with a fifteen-year-old girl in Wembley and a fourteen-year-old boy in Blackburn. Leila notes that they became ‘really weirdly close’:

This was a fast-track radicalisation happening in just a matter of weeks.

The fourteen-year-old in Blackburn turned out to be a remarkably hardened terrorist operator. From his suburban bedroom in northwest England he was already plotting a massacre of army veterans at the 2015 Anzac Day parade in Australia.2 When his case eventually went to court, the boy would be the youngest Briton to be found guilty of a terrorist offence.

It was later revealed that he had displayed an early taste for ultra-violence. His own classmates dubbed him ‘the terrorist’ because of his stated wish to behead his own teachers.3 Incredibly, across thousands of miles, this boy was already radicalising an eighteen-year-old in Melbourne through an encrypted Voice-Over Internet Protocol (VOIP). VOIP allows the user to send voice information over the internet instead of the telephone.

His radicalisation target, Sevdet Besim, aged eighteen, was an ethnic Albanian teenager from Macedonia who had emigrated to Australia with his family. A seasoned Australian ISIS fighter called Abu Khalid al-Cambodi, given this name on account of his family’s Cambodian roots, had drawn Besim and his friends towards ISIS.4 Al-Cambodi’s former name was Neil Prakash;5 he was one of the top international ISIS recruiters up until his death in a US military airstrike in early 2016.6 His online tactic was to work through various Twitter accounts, find people like Muneera or the Blackburn boy then direct them to his private messaging account for one-on-one discussions.7 In the Blackburn boy, he had found a very willing disciple.

In court, the transcript of the youngster from Blackburn’s conversations was made public. They made for grim reading. It became clear that he had transitioned with remarkable ease from experiencing raw grievance to embracing an ultra-violent Islamist ideology:

Blackburn Boy: Ok now listen. Im going to tell you what you are.

Mr Besim: Whats that

Boy: You are a lone wolf, a wolf that begs Allah for forgiveness a wolf that doesn’t fear blame of the blamers. I’m I right?

Mr Besim: Pretty much.

Boy: Mashalla [what God wills].

Mr Besim: I’m ready to fight these dogs on there doorstep. The more equipment im provided with the better but ill still go with just a knife in my hand. I want to be among those that allah laughs at...

Boy: So listen akhi [my brother]. I want you to do this on your own. Just you no one else.

Mr Besim: ok.

Boy: Im here for any advice anything you may need to know that im here, I’ll plan something in sha allah [God willing]. Also you will have to make a video and snd it to abu kambozz to snd to al hayat [a media arm of Islamic State].8

The Blackburn youth had immersed himself in online extremist material, citing Osama bin Laden as a hero. The young terrorist became an ISIS celebrity ‘fanboy’, gaining 24,000 followers within two weeks of setting up a Twitter account.9 Not only was he sending thousands of online messages to Besim down in Melbourne but he was also tweeting and messaging Muneera in Birmingham and her new friend in Wembley. In no time both girls were desperate to leave for ISIS. When this precocious young jihadist was eventually put on trial, Mr Justice Saunders who sentenced him described how chilling it was that someone who was only fourteen years old at the time could have become ‘so radicalised that he was prepared to carry out this role intending and wishing that people should die’.10

Muneera and the girl in Wembley were increasingly enthusiastic to pack their bags and go to Syria. Leila says that Muneera told her the Blackburn boy was much more hesitant about leaving the UK, saying they should wait or take their time. In contrast, the Wembley girl was ‘100 per cent committed to ISIS’ and determined to get to Syria as quickly as possible.

She urged Muneera to join her. The only problem for the thirteen-year-old was that her father had now become rather suspicious of her behaviour. When she begged to be given her passport, he locked it away. Muneera then went on a hunger strike in an attempt to emotionally blackmail her parents into giving her the passport, but without success.

By contrast, the Wembley girl grabbed her passport and without her parents’ knowledge tried to leave the UK – on two separate occasions. However, on the second attempt she was stopped at the airport by the police. They examined her phone and discovered the many messages to Muneera. Very soon there was a firm knock on the door of Muneera’s family home.

Intervention

Muneera and the Wembley girl were given an intervention provider through the Prevent counter-terrorism programme; this is pre-criminal, so they were not put on trial. Leila, as an intervention provider, works for a programme called Channel. Sitting under Prevent, Channel is about deradicalising those who have expressed sympathy for terrorist causes without crossing the line into criminality. With Muneera, this has involved getting her to express creatively what was going on in her mind when she considered joining the Wembley girl and fleeing to Syria.

A unique insight into what a thirteen-year-old is thinking when she considers fleeing to Syria is provided by a poem that Muneera wrote about the experience. She and Leila agreed to share it:

They took me towards a path I’m glad I never went down,

At first it was a paradise,

A place where all my dreams were to come true,

I was told I’d live like a princess,

But it was all a trap I was falling into,

Thinking it’s an adventure,

Painting over the real picture, Avoiding the truth,

With their lies I was drowning deep,

Convinced I was picking a rose without any thorns,

Coating every fault,

Assuming I was gathering fresh honey from a hive,

Thinking the bees will not bite,

With their bribes I was led astray,

I was believing everything said,

Not knowing I had lost my Mind,

Till I finally realise to what I was thinking at the time,

Knowing I was not all there,

The escape route was fading, yet still visible,

Now was my chance to stay away from this nightmare,

How could I have ever let this disaster overthrow?

I’m relieved to know I’m now safe,

It could have been worse,

If the star wasn’t there to guide my way,

Now every day I pray,

So something like this doesn’t come your way,

Hoping you will see the truth behind their lies,

And help save others from this distress.11

The Wembley girl took longer to deradicalise, but she and Muneera are now back at school and piecing their lives together again. Both feel angry about their experience. Their fate was a lot better than that of the Blackburn boy, whose advanced terrorist planning landed him in court and resulted in a life sentence. For the first five years he will be given a chance to demonstrate his contrition and deradicalisation; but, if the evidence is not forthcoming, he will be deemed too dangerous ever to be released.12

In spite of what emerged during his trial, the girls think the Blackburn boy was a pawn being controlled by jihadists in Australia. He was like a young gang member trying to impress the older males. In his trial, it was asserted that he adopted the style of an older teenager in his messages. However, here was a boy whose advice to Besim included developing a taste for beheading by testing it out on any loner he chanced upon.

Muneera was Leila’s youngest-ever case. But she embodied a growing trend for ISIS to target teenage girls, grooming them online to persuade them to leave their homes.13 Facilitators guide the girls through the process of getting to Syria and avoiding being caught. Research has shown they mix extremist messaging with cooking recipes or even images of kittens and coffee, to make life in ISIS territory seem relatively normal.14

Seclusion and sacrifice

In January 2015, a document appeared online titled ‘Women of the Islamic State: Manifesto and Case Study’.15 This was a conscious attempt to paint a positive picture of ISIS to pote...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Terms

- Introduction

- 1. Race to your Caliphate: The Rise of Islamist Extremism

- 2. British Salafists and Islamists: The Growing Convergence

- 3. The Islamist-Led Assault on Prevent

- 4. Identity Politics: Islamism and the Ultra Left, the Far Right and Feminists

- 5. Voices from the Frontline

- Conclusion: Winning the Battle against Extremism

- About the Authors

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index