- 243 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

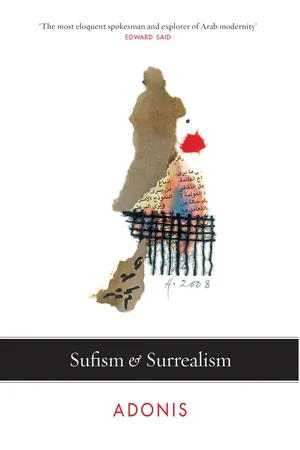

Sufism and Surrealism

About this book

At first glance Sufism and Surrealism appear to be as far removed from one another as is possible. Adonis, however, draws convincing parallels between the two, contesting that God, in the traditional sense does not exist in Surrealism or in Sufism, and that both are engaged in parallel quests for the nature of the Absolute, through 'holy madness' and the deregulation of the senses. This is a remarkable investigation into the common threads of thought that run through seemingly polarised philosophies from East and West, written by a man Edward Said referred to as 'the most eloquent spokesman and explorer of Arab modernity'.

Information

PART ONE

Sufism and Surrealism

Knowledge

Unchanging knowledge is unchanging ignorance.

al-Niffari

al-Niffari

Reject reason, stay always with reality.

al-Shabastri (13th century)

al-Shabastri (13th century)

Light is a veil.

Ibn ‘Arabi

Ibn ‘Arabi

1

Knowledge in the most profound and basic sense of the word is what connects the I to existence, the self to the object; the greater the knowledge, the smaller the distance between the two. Knowledge therefore is the connection that unites the knowing self to what is known.

According to the Sufis, existence is not an external subject that can be understood using external tools such as reason or logic. In fact, the use of logical and analytical reasoning to get a better understanding of existence only increases man’s sense of loss and confusion. It distances him from himself as well as from existence. According to the Sufis, employing such a cognitive tool is like looking at the sun with the naked eye; the eye is blinded by the sun’s brightness and the seer is more ignorant as a result. In the same way, if we depend on reason for a knowledge of existence, it will only make us more ignorant. True knowledge or gnosis comes from knowing something from within. It negates the distance between the knower and the thing known and allows the knower to realize its true essence. We can know existence, according to Sufi doctrine, only by witnessing it and practising it, i.e. through presence, taste or illumination, which are Sufi terms.

Knowledge in the Sufi sense of the word begins with the Absolute. Shibli says, ‘Knowledge begins with God (the Absolute) and it is everlasting and infinite.’ At this level, the knower does not have a state, like other creatures. At this level, as al-Bastami says, the knower’s ‘depiction’ is obliterated and ‘his identity is annihilated by an identity other than his, and his traces concealed by traces other than his.’ This knowledge will not produce absolute certainty and tranquillity as is believed. The aim of knowledge, according to Sahil ibn Abdullah, ‘is to make you surprised and confused’, because, as Dhu al-Nun al-Masri says, ‘those who have the greatest knowledge of God (the Absolute) are the most confused about him.’ Thus he himself becomes the absolute, unrestrained by any state. Were we to ask, ‘Who is the knower?’, the answer would be, ‘He was here and he has gone.’

However, this knowledge cannot be achieved while the knower is conscious of his ego and his I-ness as something external, a living manifestation embodied in the now. In fact, the ego is an obstacle to the acquisition of knowledge because its individuality is a wall that divides the knower from the known. It is possible to know existence truly only by overcoming the ego and reaching a state in which the conscious self completely vanishes. The Sufis describe this state as fana’ (annihilation). Fana’, in this sense, means the finest and richest state of permanence in existence. For fana’ is the removal of any impediments and the obliteration of the veil. In fana’, existence loses its concerns, its limitations and its chains and returns to its origins, limitless and unqualified. In fana’, therefore, a complete congruence is achieved between the subjective state of the knower and the objective state of the known world. External things, that is, the specifications of existence, are links and ties, based on illusion. Through fana’ the veil of illusion is rent apart, and from this tearing apart comes permanence in existence. Fana’ is the ‘fall of bad properties’ and baqa’ (permanence in existence) is ‘the raising of properties that are praiseworthy’. Al-Jami ordains that, in order to be aware, ‘You should distance yourself from yourself.’ Another Sufi says, ‘Inasmuch as you are alien to yourself, you will be able to acquire knowledge.’

In order to attain the state of fana’, the Sufi travels and meditates, restoring the many to the one, that is, working to purify his soul of any other connections. Fana’ is a personal, internal experience, which at the same time is an experience of being, inasmuch as it reveals being to itself. It reveals through the experience of discovery and disclosure. And if revelation in the strict Sufi meaning of the word ‘is the manifestation of the essence in the veils of the names and qualities that are sent down from heaven’, then it means knowledge or gnosis, knowledge of the Absolute. This knowledge is the mahu (obliteration) of the knower in what is known. Shibli says, ‘If I am with Him, I am myself, but I am obliterated in what He is.’ Nevertheless, this obliteration is life. Al-Junaid refers to it as follows: ‘The Absolute will make you die through him and will make you live.’ In this state, the Sufi attains utter clarity. ‘Nothing troubles him and everything is clear to him.’ Thus, by negating everything apart from God, he is led to the Absolute, to God.

There are several stages or degrees of fana’, or knowledge of the Absolute: mukashafat (uncovering), tajalli (revelation) and mushahadat (perception and sight of God).

Mukashafat (uncovering) means that the Absolute is hidden, veiled by things, and that He will remain unknown until these veils vanish. Created objects are like a veil that comes between man and his creator. Man will not attain the Absolute nor penetrate his mysteries unless he goes through a physical and mental struggle, which will lead to the obliteration of everything that separates him materially from Him.

Through mukashafat (uncovering), he achieves knowledge of the beauty and majesty of God (the Absolute), a knowledge of the mysteries of divine wisdom, divine words and divine presence and oneness with the Absolute.

In tajalli (divine revelation), the veil dissolves when the divine light appears or God reveals himself through his light and with it reveals divine things. God is light and its rays are his creation. Every being, as something originating with God, is an illumined being. The spirit, for example, is light but it is dim because it is joined to the body.

Tajalli (revelation) comes about either through contemplation or directly through God’s grace. In the case of contemplation, divine light pierces the body and enters the soul. The body is unable to bear it and the person is affected by dizziness. However, when revelation comes about through God’s grace, the person is filled with peace and calm. Through divine revelation, the darkness that envelops the secret path of ecstasy disappears.

Mushahadat (the witnessing of God) ordains that the veils that conceal the divine presence should dissolve and that the spirit be illuminated with revelation and that nothing should remain apart from the vision. Mushahadat is direct knowledge of the Absolute, obtained through seeing him and experiencing him with the eye. Since mukashafat (the uncovering) is ‘removing the cover’ that veils the divine light and since tajalli (revelation) is the encounter with the lights of mysteries, mushahadat (witnessing of God) is the reflection or the presence of these lights in the heart, which radiate off it as if off a pure mirror. These lights initially appear like a fleeting flash of lightning on the surface of the heart, and then bit by bit increase in power until they are so bright that they have no equal in any form in the light of the material world.

Inkhitaf (ecstasy) accompanies or follows this stage, and is the most distinct and the most exalted in character of any of the states of the inner life. It is the primary mystical grace. It does not come at will or through preparation but unexpectedly and suddenly, a mystical grace from God, which is destined for those individuals who are perfect. It also comes to others who work and prepare for it.

Ibn ‘Arabi distinguishes six stages of ecstasy:

In the first stage, the Sufi loses awareness of human actions (for they are the work of God).

In the second stage, he loses awareness of his powers and attributes, which are appropriated by God. God, not the Sufi, sees, listens, thinks and wants with these senses (not ‘we are thinking’, but ‘we are thought’, as Rimbaud said).

In the third stage, awareness of the self disappears, and all a Sufi’s thoughts are taken up with the contemplation of God and divine things. The Sufi forgets that it is he who is thinking.

In the fourth stage, the Sufi no longer feels that God is the one who is thinking about him or through him.

In the fifth stage, his contemplation of God makes him forget everything apart from him.

In the sixth stage, the field of consciousness narrows, the qualities of God become non-existent and God alone as an absolute being with no ties or qualities or names is revealed to the Sufi in ecstasy.

Before losing consciousness, the Sufi feels spiritually elated. He is filled with a sense of physical languor as if he is no longer in possession of his body. It is a refreshing tiredness in which his limbs do not wish to move.

Ecstasy is accompanied by other states: attainment of God is a state that some Sufis are not strong enough to bear. It is a state that controls and takes hold of the person in such a manner that they lose their independence and freedom. Some of them return to their normal state of being after having achieved ecstasy, while others remain lost or mad for the rest of their lives.

Principally, Sufis seek to achieve ecstasy, not because of the ecstasy itself or the states that precede, accompany or follow it, but because it is a means of adding to their knowledge and becoming more perfect.

2

In the Sufi vision, therefore, the Absolute (God, Being) manifests himself in two ways: the apparent and the concealed (the inner and the outer, the conscious and unconscious). The apparent is clear, rational. The concealed is hidden, heartfelt. The Absolute in its concealed form is unknown and not known, a continuous mystery. In its apparent form, it is known and embraces all things.

The Sufis describe the Absolute as ‘the hidden treasure’, recalling what Lao Tsu called ‘the door to marvels which cannot be enumerated.’

When it comes to understanding the inner world, we should distinguish between two views of existence. I will rely here on the distinction that Toshiko Izutsu uses in his book The Concept of Perpetual Creation in Islamic Mysticism and Zen Buddhism, Tehran, 1977). I will summarize what he says: The ordinary common view of things (this is the rational view) regards quiddities and essences as existing, or it sees things that exist but does not see pure existence. Existence is contained in these existing things and what lies beyond them through their quiddities. It is a quality or attribute of these quiddities. This view of existence is associated with the essentialist philosophical school.

As for the extraordinary view, it regards existing things as existence and things and essences as attributes pertaining to it. The flower, for example, exists only as an attribute of existence. In this view, things exist figuratively, through their ties, relationships and attributes. This view of reality is associated with existentialism (Izutsu, pp. 58–59).

The writer goes on to explain that there is no temporal disjunction between the inner and the external, between the Absolute and its revelations. There is no disjunction between the appearance of the sun and the appearance of its light or between the sun and its light, although the light comes after the sun and the sun exists first. In the same way, there is no distinction between the sea and the wave. The wave is a different form of the sea; it cannot exist independently of the sea. Nor can the sea exist without the wave. The sea appears in each wave in a different form. But the true nature of the sea remains one, both in the waves and in their undulations. ‘There is no distinction between the sea and the wave (the inner and the external, the Absolute and reality, reality and essence)’, as Haydar Amali asserts.

3

The Surrealists have practical knowledge of experiences similar to those moments of ecstasy described by the Sufis, and frequently write about them. Spontaneous visions occur during moments such as these. Aragon describes the state of the mind that results from it as follows: ‘First of all, each of us regarded himself as the object of a particular disturbance and struggled against this disturbance. Soon its nature was revealed. Everything occurred as if the mind, having reached this crest of the unconscious, had lost the power to recognize its position. In it subsisted images that assumed form and became the substance of reality. They experienced themselves according to this relation as a perceptible force. They thus assumed the characteristics of visual, audible and tactile hallucinations. We experienced the full power of these images. We lost the power to manipulate them and became the domain and their subjects. We held out our hands to phantoms, in bed, just before falling asleep or in the street with eyes wide open, with all the machinery of terror’ (Maurice Nadeau, The History of Surrealism, p. 46).

This recalls what the Sufis call ‘miracles’ (al-karamat); it is well known that it is sufficient for a person to cross the threshold between the conscious and the unconscious, which exists in everyone, to see another reality; this is richer and broader than conscious reality and contains intuitive knowledge, desires and unlimited and endless pleasure, beneath which conscious feelings that are constrained and enclosed by daily life collapse.

In the First Surrealist Manifesto (1924), which is considered the most fundamental of the Surrealist documents, Breton lays out his psychological and philosophical understanding and principles. We can see from it that he attributes particular importance to imagination and fantasy by describing them as the seat of freedom and its primary component, in particular free thought.

At the same time as promoting imagination and fantasy, he demotes the value of reason and logic, which can be applied to problems of secondary interest only. Absolute rationalism, which remains in fashion, as he puts it, allows man to consider only those facts and issues that form a mere part of his experience. Breton goes on to say that in today’s world, under the pretext of civilization and progress, man is deaf to any search for the truth that is not based on reason or logic, on the grounds that it is superstition or myth (First Surrealist Manifesto, p. 316).1 Breton establishes a link between dreams and original thought, which is present in man’s inner self. In the dream state, laws of logic and reason dissolve. The dream immerses man in a special universe, a world made up of internal images and an unconscious tide. When man ceases to sleep, he is completely at the mercy of his memory (ibid., p. 317), and the memory cancels the value of the dream and kills it. Breton then asks whether the dream state is not the closest approximation to original thought and the profound nature of man. Why should we not concede to the dream, Breton asks, what we sometimes refuse to attribute to reality – the weight of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Sufism and Surrealism

- Part Two: The Visible Invisible, Followed by Four Studies

- Appendix: Extracts from Surrealist Writing

- Notes

- Selected Writings on Surrealism

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sufism and Surrealism by Adonis, Judith Cumberbatch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Middle Eastern Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.