- 269 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

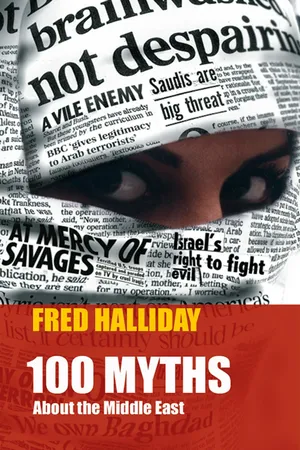

One Hundred Myths about the Middle East

About this book

Much has been written in recent years about the Middle East. At the same time, no other region has been as misunderstood, nor framed in so many clichés and mistakenly-held beliefs.

In this much-needed exposé Fred Halliday selects one hundred of the most commonly misconstrued 'facts' – in the political, cultural, social and historical spheres – and illuminates each case without compromising its underlying complexities. The Israel-Palestine crisis, the Iran-Iraq war, the US-led Gulf incursions, the Afghan-Soviet conflict and other significant milestones in modern Middle East history come under scrutiny here, with conclusions that will surprise and enlighten many for going so persuasively against the grain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access One Hundred Myths about the Middle East by Fred Halliday in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE HUNDRED MYTHS

ABOUT THE MIDDLE EAST

1

The Middle East is, in some fundamental way, ‘different’ from the rest of the world and has to be understood in terms distinct from other regions.

This idea is to be heard as often in the Middle East, where people are prone to vaunting their exceptionalism, as it is in hostile discussions in the West. If it is supposed to mean that there are distinct languages, religions, cuisines and customs in the Middle East this is indeed the case, but one that can only be made if it recognises the enormous differences between Middle Eastern societies and states themselves as much as between the region and the rest of the world. However, if it is meant to mean that the forms of social and political behaviour found in the region are somehow unique or cannot be explained in broad analytic terms used for other parts of the world, the claim is false. The main institutions of modern society – state, economy, family – operate in the Middle East as they do elsewhere. The modern history of the region, conventionally dated from 1798 – the French occupation of Egypt – is very much part of the broader expansion of European military, economic and cultural power in modern times, and has to be understood in broad terms comparable to the experience of other subjugated and transformed areas of the non-European world – Africa, Latin America, South Asia and East Asia.

The main features of Middle Eastern society to which those claiming its exceptionalism draw attention – dictatorship, rentier states, national-religious ideologies, subordination of women – are by no means specific to it. Of course, political actors in the region, be they conservative monarchies or radical Islamists, like to proclaim their originality and uniqueness, but this is part of the drive for political legitimacy, not a historical or analytic statement. If the region is supposed to be unique because of the impact of oil on its economies and societies, a brief study of other oil-producing states such as Indonesia, Nigeria, Venezuela and, above all in recent years, Russia and the former Soviet republics, will soon dispel any such illusion. If it is said to be unique because of the ferocity of its inter-ethnic conflicts, particularly the Arab-Israeli dispute, this too does not survive any comparative judgement: far more people have been killed in inter-ethnic conflicts in Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia and, be it not forgotten, twentieth-century central Europe, than in the more than half-century of the Palestine question.

Terrorism, too, is by no means peculiar to Islam or the Middle East; within the modern history of the region all religions have been used for purposes of mass murder and ethnic discrimination – as Jewish underground groups like Lehi and Irgun demonstrated in the 1940s, and as the Christian Maronites showed in Lebanon in the 1970s and 1980s. Elsewhere in the world, not to forget one of the historic proponents of terrorism along with the Irish and Bengalis in the nineteenth century and beyond, were the Christian Armenians. That particular bane of the 2000s, suicide bombings, were first pioneered by the (Hindu) guerrillas of Sri Lanka, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. All regions, religions and peoples, like individuals, are in some ways unique in origin and characteristics; but characteristics shared with others are far greater by degree than those which distinguish. It is for this very reason that states, peoples and demagogues from all directions make such efforts to exaggerate their own, and their enemies’, singularity.

The Middle East therefore shares far more with the rest of the world than it exhibits differences: all its societies, states and peoples are part of a world economy and subject to its changes; all uphold principles of national independence and culture and reject what they see as alien impositions; all protest when they are not accorded the rights and respect that the modern world, rightly, proclaims as being universal entitlements.

Beyond all of this, its peoples share the human emotions common to all mankind. In the words that Shakespeare wrote for his Jewish character Shylock in The Merchant of Venice: ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ It is here, in the need and demand for universal respect and for a just place in the modern world, that the greatest source of anger and confusion in the Middle East resides – not in some supposed singularity, irrationality or peculiarity of religion, race or region. The roots of so-called ‘Arab Rage’ lie not in some purported cultural or religious pecularity of the Arabs, but in the adherence by the peoples of the Arab world to the universal claims of justice and equality which the rest of the world has propagated these two centuries past, and has now largely taken for granted.

2

The Middle East is a region dominated by hatred and solemnity; its peoples have no sense of humour.

Such things are not quantifiable; there is no UN Global Intercultural Hilarity Index. But my own impression, based on having visited several other regions of the world, including Eastern Europe, North and South America and East Asia, is that the peoples of the Middle East are less thin-skinned, more able to laugh about their rulers, their neighbours and themselves, than those of any other part of the world. You can spend weeks in Western Europe or the US without ever hearing a political joke, whereas in the Middle East no conversation, party or meeting with a friend in a café is complete without some anecdote, nokta (Arabic: ‘joke’; literally, ‘point’) or report of the indiscretions of the powerful, real or imagined.

There are long traditions of such story-telling and jokes, some involving complex linguistic and literary variations and puns, in several Middle East countries – notably featuring Mullah Nasruddin in Iran and Nasrettin Hoca in Turkey. Jewish culture has its own long traditions and styles of humour, although with Zionist Jews, as with other peoples the world over who have become devotees of nationalism (the Irish being another case in point), this tradition has been eroded in recent times. Israeli humour, while bitter and literary in its own way, pales before that of the Jewish diaspora. However, the very discredit in which so many Middle Eastern rulers are held means that jokes about and against them abound, much as they did in Eastern Europe under Soviet communism. Many of these stories are of an unprintable kind, involving lecherous mullahs; donkeys; the more outrageous claims of religious authorities be they mullahs or rabbis; personal hygiene; and the IQ of sons of incumbent presidents, if not of the presidents themselves. All of this, and more, is explored in a fine book by Khalid Qishtayni, Arab Political Humour.

In Iran, one of many examples of popular humour could be seen in Tehran in the summer of 1979, just after the revolution: at traffic lights little boys would be selling the usual oddments – chewing gum, shoe polish etc – but they also offered something else, a little volume titled Kitab-i shukhi-yi ayatollah khomeini (‘The Ayatollah Khomeini Joke Book’). This turned out to be a selection of Khomeini’s most preposterous writings on sex, hygiene and all matters personal and intimate. Another case of such anti-authoritarian Iranian irony came in 1989 with the controversy over Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses. The novel, which includes a satirical treatment of the early history of Islam, was denounced by Khomeini and became the subject of an international controversy. No right-thinking supporter of the Islamic Republic could be seen to indulge such a tome. But an Iranian opposition group, knowing well the suspicious and imaginative propensities of the people, and precisely in order to attract a wider audience, started a new radio station called ‘The Voice of The Satanic Verses’. Years later I met an Iranian man, a merchant from a provincial town on his first visit to the West. ‘Please tell me,’ he said, ‘what did dear Mr Rushdie say? It must have been something great, because he annoyed those stupid mullahs so much!’

3

The incidence of war in modern times in the Middle East is a continuation from earlier times of violence and conquest, and of a culture that promotes violence.

The incidence of war in the post-1945 period has nothing to do with the earlier incidence of wars, or with a ‘culture of conflict’ inherited from pre-modern times. States, warriors and propagandists make much of such continuity, be it the Israelis invoking the warrior-king David, Saddam Hussein the Battle of Qadissiya or the Turks their conquering sultans; but this is symbolic usage, not historical explanation. As for there being a ‘culture of violence’ in the Middle East, this is a nebulous phrase that is almost without analytic purchase: certainly there are values and practices in these societies, such as parading small boys with guns and holding pompous military revues, that are usable for militaristic mobilisation and indoctrination, but so are there in other cultures – notably those of the former imperial powers of Europe, the US and Japan. The history of Europe in the twentieth century, and the brutality visited by some of its rulers on their own peoples, far outstrips anything seen in the modern Middle East.

4

Middle Eastern peoples have a particular sense of ‘history’, their own great part in it at some point in the past, their more recent humiliations and the need to prove themselves in terms of it.

Throughout the Middle East there is frequent reference to, and use of, ‘history’ to explain and justify current activities and events. However, according to any plausible criteria of the instrumentalised past, such a use and abuse of history is found just as much in other parts of the world – for example, the Balkans, Ireland, East Asia, Russia – as in the Middle East. Moreover, as with religious texts and traditions, the invocation of history reflects not the real effect of the past on the present, but the ransacking, selection and, where appropriate, invention of an ever-powerful history to justify current concerns. ‘History’ is here not a form of explanation, but of ideology.

5

Social behaviour, including attitudes to power, can be explained in terms of a distinctive, identifiable mindset, of all Arabs or Muslims or, more frequently, of Egyptians, Iraqis, Saudis, Turks and their various specific counterparts.

All peoples, and the politics and population of each modern state, have some distinct elements of political culture. Moreover, every state and society requires there to be certain values necessary for the sustenance of that system. But this is distinct from claiming some specific national ‘mindset’ based on ethnic, historically essentialist and too often stereotyped characteristics attributed to a people. Many of the ‘special’ attributes assigned so easily to one people or another, often by representatives of those peoples themselves, are shared with other peoples. A parallel process is latent in the often-made assertion as to some saying, folk wisdom or phrase supposedly embodying the uniqueness and history of a particular people: on closer, and comparative, inspection these nearly always turn out to be local variants of much wider, if not universal, observations.

6

Different European nations have ‘special’ relations to the Arab world and/or Middle East – e.g. the English, Greeks, Spanish, Germans, Irish …

The claim of some ‘special’ relatio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Preface

- One Hundred Myths About The Middle East

- A Glossary of Crisis: September 11, 2001 and its Linguistic Aftermath

- Index of Myths

- Index of Names

- Copyright