- 366 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Arab–Israeli conflict goes far beyond the wars waged on Middle Eastern battlefields. There is also a war of narratives revolving around the two defining traumas of the conflict: the Holocaust and the Nakba. One side is charged with Holocaust denial, the other with exploiting a tragedy while denying the tragedies of others.

In this path-breaking book, eminent political scientist Gilbert Achcar explores these conflicting narratives and considers their role in today's Middle East dispute. He analyses the various Arab responses to the Holocaust, from the earliest intimations of the genocide, through the creation of Israel and the occupation of Palestine, and up to our own time, critically assessing the political and historical context for these responses.

Achcar offers a unique ideological mapping of the Arab world, in the process defusing and international propaganda war that has become a major stumbling block in the path of Arab–Western understanding.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

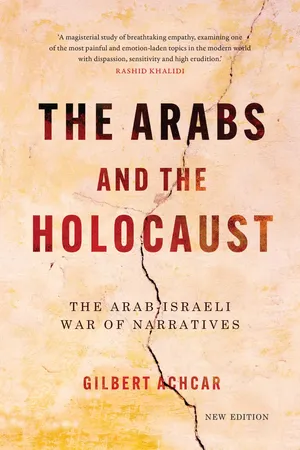

Yes, you can access The Arabs and the Holocaust by Gilbert Achcar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Holocaust History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE TIME OF THE SHOAH

Arab Reactions to Nazism

and Anti-Semitism

1933–1947

Prelude

It ought to be a truism that ‘the Arabs’ do not exist – at least not as a homogeneous political or ideological subject. Yet such use of a general category known as ‘the Arabs’ is common in both journalism and the specialist literature. ‘The Arabs’ are supposed to think and act or react in unison. Of course, like ‘the Jews’ or ‘the Muslims’, ‘the Arabs’ as a politically and intellectually uniform group exist only in fantasy, engendered by the distorting prism of either ordinary racism or polemical fanaticism.

Like any large, diverse group, the Arab population is criss-crossed by different ideological currents, shaped by varied forms of education and political experience in different countries, a circumstance no well-informed work on political thought in the Arab world fails to point out. Only a perception distorted by ‘Orientalism’, in the pejorative sense of the term made famous by Edward Said – i.e. the cultural essentialization of the peoples of the East that reduces them to a stereotyped immutable being or ‘mind’1 – can obscure the very deep divisions in the Arab world.

The diversity of the Arabs’ historical relations to Nazism and Zionism is no less pronounced. There have even been a few Arab allies of the Zionist movement: recall the Palestinian ‘collaboration’2 and the unacknowledged ‘collusion’ of leaders who had ties to the British, such as King Abdullah of Jordan,3 or allies motivated by the idea of making common cause with the Zionists as ‘enemies of their enemies,’ notably some Christian Maronites in Lebanon.4

In the Arab anti-colonial independence movement, whose opposition to the Zionist project in Palestine reflected what was by far the dominant Arab attitude in the 1930s and 1940s, we may distinguish four basic ideological currents:

1) the liberal Westernizers

2) the Marxists

3) the nationalists

4) the reactionary and/or fundamentalist Pan-Islamists.

2) the Marxists

3) the nationalists

4) the reactionary and/or fundamentalist Pan-Islamists.

Note that none of these currents has a monopoly on the central value inspiring it. Thus there is widespread adhesion to Islam among liberal Westernizers and nationalists. Nationalism, moderate or radical, animates Westernist liberal advocates of independence and, in a specifically religious form, Pan-Islamists as well. Similarly, it can be argued that both Marxists and most nationalists are Westernizers who even, at times, embrace the same liberal values.

Moreover, each current comprises several distinct variants, and there are a number of intermediate and combined categories. Regarding nationalism in particular, we may distinguish a right wing that often works in close alliance with Islamic fundamentalism, a left wing influenced by Marxism and a liberal version.5 On certain questions, the positions of these sub-groups can differ sharply.

Nevertheless, a qualitative difference sets each of the four major categories apart: the nature of its guiding principle, its determinant system of political values. They choose their political positions with reference, first and foremost, to a distinctive political and ideological system of thought – liberalism, Marxism, nationalism or Islam conceived as a source of political inspiration adapted to contemporary conditions.

CHAPTER 1

The Liberal Westernizers

As used here, ‘Westernism’ has nothing to do with the concept of ‘Occidentalism’ forged in symmetrical opposition to Said’s ‘Orientalism’ as a caricature for a certain Islamic perception of the West.1 Nor is it my intention to stand the concept of Orientalism on its head in order to paint the Westernizers as unconditional admirers of the ‘West’ and its governments. The term is, rather, patterned after nineteenth-century Russian ‘Westernism’.

The Russian Westernizers, in opposition to the Slavophiles, urged adoption of the Enlightenment values that dominated Western Europe together with the industrial civilization that, in their view, functioned properly only when accompanied by those values.2 Russian Westernism did not imply uncritical admiration of Western Europe but, rather, a set of values that might equally be described as ‘modernist’ and could perfectly well accommodate a political critique of the West.3 Thus, alongside liberal Westernism, there existed a Marxian Westernism and even a Europeanist Russian nationalism. The situation is no different in the Arab world.

Following Nadav Safran, I use the word ‘liberalism’ here not in its nineteenth-century sense, designating a limitation of the role of the state, individualism and ‘the sanctity of property,’ but rather to mean ‘a general commitment to the ideal of remolding society on the basis of an essentially secular conception of the state and rational-humanitarian values’.4

Steeped in a democratic, humanist culture, the Westernizing liberals among the advocates of independence in the Arab world opposed National Socialism from the outset – a stand that by no means mitigated their anti-colonialist hostility to Zionism. As those best qualified to criticize the premisses of Zionism while defending the values of Western anti-fascist culture, the Westernizing liberals were a deep embarrassment to the Zionist movement. They did not, however, hold the greatest appeal for the Arab masses, given the contradiction between those very values and the colonialist behaviour of the Western powers posing as their champions – a problem still acutely relevant in the Arab world today.

The twofold denunciation of Nazism and Zionism made it possible to contest the use of Nazi abominations as a way of legitimizing the Zionist enterprise. The liberals’ main argument was based on plain common sense: why should the Palestinians have to pay for the Nazis’ crimes? This objection stands as a constant in the long history of the Arab polemic against Zionism; the various ideological currents of the Arab world have all taken it up.

My own father, Joseph Achcar, a pro-independence but also Francophile Lebanese, provided an early statement of this argument. It appeared in the dissertation he submitted in 1934 to the University of Lyons for a doctorate in law, in which he deplored Hitler’s assumption of power the previous year:

It goes without saying that we condemn, as the world’s conscience has done since then, the atavistic, savage conception that … professes to purify the German nation by eliminating elements foreign to it …

A government that springs from this reactionary, antiquated attitude readily ostracized the heterogeneous minorities among the people. The result was to drive away ‘the undesirables,’ the Jews, who had to appeal to the hospitality of other countries. It was accorded to them only on precisely defined conditions, [given] the difficulty of finding them employment in the current period of economic crisis.

The Zionist leaders accordingly returned to the assault on the obstacles to creating a Jewish state in Palestine …

It is not possible to redress one injustice, if an injustice has been committed, by another, more serious and more costly injustice. That the Jewish people inhabited Palestine more than twenty centuries ago is beyond doubt. That it should aspire, after so long an interval, to take the country back and lay down the law there is sheer utopia.5

This point of view was anything but exceptional. Indeed, there is every reason to wonder why liberal Westernist anti-colonialism, the vehicle of the Enlightenment in the Arab world, has attracted so much less attention than the most reactionary Arab currents, even those that were infinitely less influential.

Israel Gershoni, a specialist in Egyptian intellectual history at the University of Tel Aviv, has taken up the task of ‘deconstructing the hegemonic narrative’ that maintains, contrary to all the documentary evidence, that a majority of Egyptians supported Nazism in the 1930s.6 His research established that ‘the overwhelming majority of Egyptian voices – in the political arena, in the liberal westernizers 43 intellectual circles, among the professional, educated, urban middle classes and even in the literate popular culture – rejected fascism and Nazism both as an ideology and a practice, and as “an enemy of the enemy.”’7

The Egyptian public’s attitude toward fascism and Nazism was expressed principally through three types of representation. The first, imperialistic representation, viewed fascism and Nazism as imperialist forces; the second, totalitarian representation, perceived the Third Reich and the fascist regime in Italy as extreme forms of modern totalitarianism. And the third, racist representation, scathingly denounced the ideology of Nazism and its racist theories and practices.8

Gershoni paid special attention to the Islamic variant of liberal Westernism in Egypt. In a study on Egyptian liberalism’s attitude towards Nazism from 1933 to the outbreak of the Second World War, he focuses on the weekly review Al-Risāla, the first issue of which appeared in 1933.9

Boasting a circulation that rose, late in the decade, to 40,000 copies, a third of which were sold in Arab capitals beyond Egypt’s borders, Al-Risāla provided a forum for some of the most prestigious Egyptian and non-Egyptian Arab intellectuals of the period: its contributors included Ali‘Abdul-Rāziq, Ahmad Amīn, ‘Abbās Mahmūd al-‘Aqqād, Muhammad Husayn Haykal, Tāha Hussein, Tawfīq al-Hakīm,10 Mahmūd Taymūr and Sāti‘ al-Husri.11 Together with a clear Arabist and Islamic orientation (Al-Risāla means ‘the message’ – an allusion to that of the Prophet Muhammad) along reformist lines,

it regularly devoted space to a methodical, highly critical review of internal developments in Nazi Germany and in fascist Italy, as well as of the policies of Hitler and Mussolini in the international arena. It was not a solitary voice in doing so. Consistent support of liberal democracy and liberal values, attended by the rejection of fascist and Nazi totalitarianism, can also be found, for example, in the monthly Al-Hilal, in the daily Al-Ahram, and in the illustrated weekly Ruz al-Yusuf [Rose al-Yūsuf] throughout the entire decade.12

Gershoni shows that the critiques appearing in the review were comparable to the best analyses and refutations of Nazism published in Europe. The review denounced not only the racial exclusion organized by National Socialism, but also the ‘racist madness’ of its scientific pretensions and their translation into medical practice. Avoiding the tra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Words Laden With Pain

- Part 1: The Time of the Shoah Arab Reactions to Nazism and Anti-Semitism 1933–1947

- Part 2: The Time of the Nakba Arab Attitudes to the Jews and the Holocaust from 1948 to the Present

- Conclusion: Stigmas and Stigmatization

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index