![]()

Part One

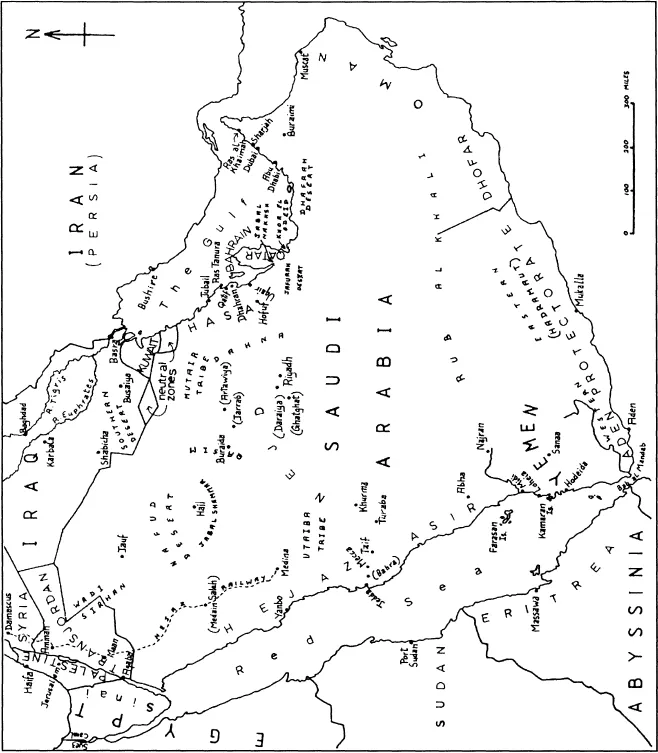

Arabia circa 1939

Adapted from the map by Cleland Laidlay. First published in: Britain and Saudi Arabia, 1925–1939: The Imperial Oasis, by Clive Leatherdale, published by Frank Cass in 1983. Reproduced with kind permission by Frank Cass Publishers.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Arabia on the Eve of the Emergence of Wahhabism: Economy, Society, Politics

The Saudi state arose in Arabia in the eighteenth century on the basis of Wahhabism, a Muslim reform movement. The key to understanding the Wahhabi ideology – and the causes of the emergence, development, downfall and renaissance of the state that is today known as Saudi Arabia – lies first and foremost in a study of Arabian society. It should be stated at the outset that this book concentrates on the central, northern and eastern regions of the peninsula: Najd and al-Hasa (the Eastern Province). Yemen and Oman are outside the scope of the present study (except insofar as events there had a direct connection with Saudi Arabia), not only because they have remained independent of Saudi Arabia, but above all because of their pronounced peculiarities: geographic, historical, economic, ethnic and religious. These provide sufficient grounds for treating their inhabitants as separate peoples with their own socio-political structures and destinies.

Mecca and Medina, the holy places of Islam, were too tempting a booty for any Middle Eastern empire to permit Hijaz, where they are located, to preserve its independence. Although the socio-political and economic situation of Hijaz differed very little from that of Najd, the latter practically never experienced foreign domination. The status of Hijaz as a province first of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, and then of Egypt and the Ottoman empire, as well as the hajj (pilgrimage) and related trade and other economic activities, made it different from its neighbours. Thus when we refer to ‘Arabian society’, we mean principally that of Najd, the cradle of Wahhabism and the Saudi state, together with the adjacent regions in the north and south.

Two ‘sand seas’ – the Great al-Nafud in the north and the Rub al-Khali in the south – determine the approximate northern and southern boundaries of Najd. In the west, Najd is bounded by the Hijaz mountains and in the east by the coastal strip of the Gulf.* Overall, the territory slopes gradually from west to east. The climate is characterized by regular fluctuations of temperature – an intense dry heat in summer and a pronounced cold in winter. Almost all the area is arid and years without any rains are frequent. But rain is only a partial blessing. Sayls (stormy mud streams) sweep the wadis (valleys), frequently with catastrophic consequences.

The most famous valley is Wadi al-Rum, which begins in Hijaz, to the north-east of Khaibar, continues some 360 km to the east, vanishes in the sands and then reappears under the new name of al-Batina, to end near Basra (Iraq) some 1,000 km from its starting-point. Other major valleys are wadis Hanifa, al-Dawasir and Najran. Subsoil waters are closest to the surface in wadis, making life possible. It was in Wadi Hanifa that several large oases emerged and became the cradle of Wahhabism and the Saudi dynasty (the Al Saud).

Buraida and Anaiza, the main towns of the province of Qasim, are located in Wadi al-Rum. Najd is divided into regions none of which has clear boundaries. Historically, however, these regions had a kind of geographic unity. The most important of them are the central regions, al-Arid (crossed by Wadi Hanifa), Mahmal, Sudair and Washm. The capital Riyadh is located in al-Arid. The main southern regions are al-Kharj, famous for its deep wells and basins; al-Aflaj, where ancient underground irrigation canals have survived; al-Dawasir; and, lastly, Najran. The northern regions of Qasim and Jabal Shammar have always had an important role. The rival towns of Buraida and Anaiza are located on the route from Basra to Medina, and so have always been major trading centres. Jabal Shammar lies to the south of al-Nafud and is the northernmost area of Najd.

Artefacts and documents from the eighteenth century reveal isolated fragments of Arabia’s social life and later information allows us to reconstruct at least a general outline. The slow development of the economy and the stable, age-old social structures allow us to assume that life in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Arabia had not changed greatly since medieval times. For the overwhelming majority of people in Najd, al-Hasa and Hijaz, life was connected chiefly with two kinds of economic activity – irrigated farming in the oases and nomadic animal husbandry.

Irrigated farming

The arid, subtropical climate in most of the peninsula means that artificial irrigation is necessary for farming. More or less abundant subterranean waters reach the surface only in the eastern regions of Arabia. In other regions, the sources of irrigation are wells. Collected rainwater and sayl streams are used less frequently. Water sources are sometimes dozens or even hundreds of kilometres apart. But in Najd (where water-bearing layers are close to the surface of the soil) and al-Hasa a fairly dense concentration of oases can be observed.

Well-building demanded considerable labour and resources; primitive water-raising mechanisms used camels, mules and asses. Naturally, this restricted the area of irrigated farming and the volume of agricultural production. A 10-m-deep well with a water-raising device was enough to irrigate 1 feddan (approx. 1 acre).1

Dates were the main crop in the northern and central regions of Arabia. They were consumed in various forms and were the only agricultural product of vital importance that met the needs of the settled and nomadic population in favourable years. Date palms required constant attention and only began fruiting fully some fifteen years after planting. Second to dates were cereals – barley, millet, wheat and oats. It is known that cereals were exported from Najd to Hijaz in certain years. Rice and cotton were grown in some areas. Vegetables and fruit were grown where water was abundant: al-Taif, for example, was famous for its gardens.

Irrigated plots yielded relatively good crops, but the total volume of production was insignificant because of the limited area of arable land, the shortage of fertilizers and the primitive agricultural methods. Repeated droughts, whose catastrophic consequences were reported both by the Arabian chroniclers and by European travellers, meant that there was no guarantee of stable crops even on irrigated land. Some wells dried up completely during prolonged droughts. The crops perished, the cultivated areas decreased, even the date palms ran wild and then withered, and the inhabitants starved, died or left long-occupied settlements. When the rains came again, wells and reservoirs filled with water and the peasants resumed their sowing and took care of the surviving date palms. But oases could be swallowed by the desert and disappear for ever.

Both droughts and the rare, drenching rains could prove the peasants’ enemies. Strong sayls might carry away the upper layer of soil from the fields together with the crop, sweep away houses and destroy the fruits of many long years of labour. Locusts often devoured all the plants and left people with no means of subsistence. Food shortages on the eve of the new crop were not infrequent. Wallin reports, for example, that the inhabitants of Tabuk appeased their hunger in the spring almost exclusively by consuming wild grass, ‘eaten raw, or merely boiled in water, without anything more substantial in addition’.2 Frequent epidemics (cholera and plague) depopulated whole villages.

The narrow economic base, the hostile forces of nature (the social factors will be discussed later), the primitive agricultural technology and the isolation of the oases all resulted in a very slow rate of economic development. Oasis farming was characterized by a fragmentation of effort and was undertaken by small peasant groups and individual families. There were no large-scale irrigation facilities or huge tracts of irrigated and cultivated land in medieval Arabia. Combined with the isolation of the oases, this meant that there was no need for a centralized government.

Nomadic and semi-nomadic animal husbandry

There were two main types of animal husbandry among the Arabian nomads: camel-breeding and sheep- or goat-breeding. The nomads who mainly or exclusively bred camels, ‘almost the most universal of all animals’,3 were considered the ‘genuine bedouin’. Camel milk (fresh or sour), cheese and butter were often their only food for many weeks. On special occasions, animals were slaughtered and their meat and fat were eaten. Camel wool was used for clothes, their skin for various articles, manure for fuel, and urine for washing and for medical purposes. The hardy, undemanding camel was irreplaceable when crossing arid areas. ‘The camel is such an important animal in the desert that had it perished, the whole population would follow it,’4 notes Volney.

However, the widely quoted saying by the Austrian orientalist Sprenger, ‘The bedouin is a parasite of the camel,’ is nothing more than a witticism. The camel-breeding nomads’ labour was hard and required well-tested skills. They had to know how to exploit their pastures, drive camels from one grazing area to another, treat the animals when they were sick, milk the female camels, cut the wool and so on. Younger camels were trained to perform various tasks and to walk saddled and loaded. The bedouin dug and maintained wells in the desert.

The life of the bedouin was full of privations. In the rare snowy winters, young camels perished, female camels stopped giving milk and the livestock starved. A dry summer, too, spelled hardship and danger. Even the scarce reserves of dates and grain came to an end and poor bedouin ate wild tubers and fruit; many of them died of malnutrition. Their summer pastures usually lie close to cemeteries.5

The famous Arab horses – a source of pride for those who owned them and of envy among those who did not – were used only for military purposes and for show. In their long roamings, horses needed either a water reserve or camel milk. To support that noble animal, a poor bedouin would partly deprive his family of water and milk.

Those who mainly or exclusively bred sheep and goats were usually known as shawiya. Since their ability to cross arid areas was limited, they roamed over a radius of several hundred kilometres to pastures that were close to water sources. Travelling over relatively short distances in areas with permanent water sources, sheep-breeders could engage in farming. They ceased migrating in the agricultural seasons to look for date-palm groves and cereal fields. Farming became the main occupation of a substantial number of sheep-breeders.

This combination of farming and nomadic animal husbandry in northern Najd is described by Wallin:

In consequence of the close and intimate relations, before adverted to, which connect the two classes of the Shammar, we find the villagers, to a certain degree, still clinging to the customs and manners of nomadic life, while the Bedawies, on the other hand, apply themselves to avocations, which are generally regarded as not becoming. A great many of the former wander during the spring with their horses and their herds of camels and sheep to the desert, where they live, for a longer or shorter time, under tents as nomads, and most of the Bedawy families possess palm-plantations and corn-fields . . . which they cultivate on their own account.6

Burckhardt reports that a subdivision of the Harb tribe in Hijaz:

possess some watering-places, situated in fertile spots, where they sow corn and barley; but continue to live under tents, and pass the greater part of the year in the desert.7

There were, as a rule, no rigid boundaries in the sense of economic activities between nomadic camel-breeders, semi-nomadic sheep-breeders and settled people. Many camel-breeding bedouin started sheep-breeding; and a part of the...