- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

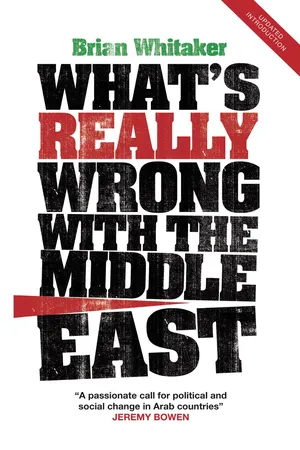

What's Really Wrong with the Middle East

About this book

The problems in the Middle East run deeper than dictatorship. Inspired by the popular uprising that overthrew Tunisia's president, Arabs across the Middle East are demanding change. But achieving real freedom will involve more than the removal of a few dictators. Looking beyond the turmoil reported on our TV screens, Guardian journalist Brian Whitaker examines the 'freedom deficit' that affects Arabs in their daily lives: their struggles against corruption, discrimination and bureaucracy, and the stifling authoritarianism that pervades homes, schools and mosques as well as presidential palaces. Drawing on a wealth of new research and wide-ranging interviews, Whitaker analyses the views of people living in the region and argues that in order to achieve peace, prosperity and full participation in today's global economy, Arabs should embrace not only political change but far-reaching social and cultural change as well.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What's Really Wrong with the Middle East by Brian Whitaker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Thinking inside the box

MOUNIR IS IN his second year studying law at Cairo University. Well, not exactly at the university. With 9,000 students in his class, there isn’t room for them all. “The majority of students are basically like me – people who don’t attend,” he said. “We just show up for the exams and in four years we graduate. Then we get automatic membership of the Bar Association and become practising lawyers.” Mounir doesn’t bother much with textbooks, either. He explained:

The textbook is usually a manuscript written by the professor teaching the class. There are photocopy shops outside the university and they commission former graduates of the law school to summarise the textbook. That’s what I buy, 20–30 pages at a time.

The summary is usually a question-and-answer sheet. When there is a matter of controversy it lists the various opinions and then summarises the author’s view. Over the years this has become known as “ra’i al-duktoor” – the doctor’s opinion. There’s a big highlighted section in a box – so clear that you can’t miss it – titled “Ra’i al-Duktoor”. This is what you need to memorise because this has to be your opinion too.

I memorise these and then I go for the exam. Basically, you analyse all the previous years’ exams and identify the main questions. Typically, you need to write the doctor’s opinion as the correct one after reviewing the literature.1

Unlike Mounir, Khaled Diab did attend classes while studying economics in Egypt, and one of the things he learned was not to ask too many questions:

There was an emphasis on making profuse notes when you attended lectures. You tried to get the professor’s [exact] wording because you would be expected to regurgitate that in the exam and the closer you came to how the professor put it, the higher the grade you were likely to get. That’s partly a practical thing because often the exams are marked by assistants who are told to look for certain keywords and so on, but it’s also an issue of prestige and authoritarianism in the sense that professors expect you to act like a disciple – what they say is gospel.

I would often question the professor’s thinking in lectures and exam papers, and that hurt my grades.2

Education may not be the most obvious of the Middle East’s problems, and yet in many ways it is central. As in other parts of the world, school, college and university, together with upbringing in the home, are key factors that shape the mindset of each new generation. Through these mechanisms the ideas and attitudes of elders – the accumulated baggage of past and present – are carried forward into the future. The way a society rears and educates its young thus provides a window on the society as a whole – its strengths and weaknesses – as well as pointers to how the bonds of the past might be broken. In the Middle East, more specifically, the dominant styles of education and child-rearing help to explain why autocratic regimes have proved so resilient and why so many people in the region submit passively to restrictions on their rights and freedoms that others would reject as intolerable. It is all very well to talk about promoting freedom and democracy in the Middle East, as the United States did constantly under President George W Bush, but while mindsets remain unchanged such hopes are just a mirage. Change – if it is to be meaningful – must begin in people’s heads.

Education in the Arab countries is where the paternalism of the traditional family structure, the authoritarianism of the state and the dogmatism of religion all meet, discouraging critical thought and analysis, stifling creativity and instilling submissiveness. These problems begin in the home, the 2004 Arab Human Development Report observed:

Studies indicate that the most widespread style of child rearing in Arab families is the authoritarian mode accompanied by the overprotective. This reduces children’s independence, self-confidence and social efficiency, and fosters passive attitudes and hesitant decision-making skills. Most of all, it affects how the child thinks by suppressing questioning, exploration and initiative.3

Schooling continues this process, and reinforces it:

Communication in education is didactic, supported by set books containing indisputable texts in which knowledge is objectified so as to hold incontestable facts, and by an examination process that only tests memorisation and factual recall.4

Curricula, teaching and evaluation methods, the AHDR noted, “do not permit free dialogue and active, exploratory learning and consequently do not open the doors to freedom of thought and criticism. On the contrary, they weaken the capacity to hold opposing viewpoints and to think outside the box. Their societal role focuses on the reproduction of control in Arab societies.”5

The main classroom activities, according to a World Bank report, are copying from the blackboard, writing, and listening to the teachers. “Group work, creative thinking, and proactive learning are rare. Frontal teaching – with a teacher addressing the whole class – is still a dominant feature … The individual needs of the students are not commonly addressed in the classroom. Rather, teachers teach to the whole class, and there is little consideration of individual differences in the teaching-learning process.”6 One investigation into the quality of schooling in the Middle East found students were taught to memorise and retain answers to “fairly fixed questions” with “little or no meaningful context”, and that the system mainly rewarded those who were skilled at being passive knowledge recipients.7 Although that study was published in 1995, the World Bank’s 2008 report concluded that many of its criticisms still applied thirteen years later: “Higher-order cognitive skills such as flexibility, problem-solving, and judgment remain inadequately rewarded in schools”.8 Moreover, the few Arab countries that have recognised this deficiency and tried to introduce such skills as an educational objective have generally failed to change the classroom practices. Egypt, for example, tried sending teachers to Europe to learn modern teaching methods but when they returned to Egypt they quickly reverted to the old ways. 9

If this makes young Arabs well-equipped for anything at all, it is how to survive in an authoritarian system: just memorise the teacher’s words, regurgitate them as your own, avoid asking questions – and you’ll stay out of trouble. In the same way, the suppression of their critical faculties turns some of them into gullible recipients for religious ideas that would collapse under serious scrutiny. But it ill-equips them for roles as active citizens and contributors to their countries’ development.

Moroccan writer Abdellah Taia sums up the result in one word: detachment. Detachment or disengagement, not just from power and politics, but from the realities of daily life. “It’s as if the things you study in school, in university are not real – just things you study,” he said. “Maybe you discuss them with friends, but it’s only discussion. I think Moroccans – and Arabs in general – are very detached from things that really matter.

“In Morocco we have this idea that we have to be proud of our country, of our religion, of our family, of our king, and if foreigners ask we tell them it’s good. But at the same time it seems as if we are not Moroccan society – that society is something abstract. We are in it but we don’t see that society is us, and that we can influence it or change it.” He continued:

There was a woman in Mohammedia, near Casablanca, who had three daughters and was pregnant again. Her husband obliged her to have a test and when they found the baby was another girl, he said: ‘You are a woman who gives birth only to girls, and I want a boy.’ So he forced her to give him permission to marry another woman. Later that day the wife took her three daughters and they jumped on the railway line together and were killed by a train. All of them.

When I heard this story I was shocked and I knew what people would say: that she wasn’t a Muslim any more and would go directly to hell because of her suicide.

Here was this woman resisting with the last weapon she had got, which was her body. She was already condemned by her husband and even her last cry, her act of resistance (because that is what it was), was again misunderstood. What she did reflected the ignorance, the machismo of the men, the paternalism – everything.

If something like that happened in France or Britain there would be a huge debate. Everyone would be concerned, the country would be questioning itself and asking: Why? But in Morocco it’s “OK, well, she’s going to hell and it’s not our affair, and anyway we don’t talk about death in our house because it brings bad luck.”

This is what I mean by detachment. There is no real thinking about anything, it’s just like... It’s like when you make bread and the dough sticks to your fingers. For me, this is the right image for a lot of things in Morocco and the Arab world. It’s sticky and we are stuck in it. We can’t go back and we can’t go forward.10

MASS EDUCATION IN Arab state-run schools developed mainly in the latter half of the twentieth century and generally had two main objectives: to combat illiteracy and inculcate a sense of national identity. Starting from a very low base, Arab countries have made considerable progress in developing literacy and the biggest gains have been in female education: women’s literacy rates have trebled since 1970 and school enrolment rates for females have more than doubled.11 Taking into account the resistance to female education from traditionalists in some countries, this is a noteworthy achievement. In 1970, for example, Saudi Arabia had only 135,000 female students – 25 per cent of the total – but by the turn of the century the numbers were almost equal – 2,405,000 males and 2,369,000 females. According to the kingdom’s education ministry, “Promoting the concept of equal educational opportunities for the sexes posed a problem but one that was ameliorated by Islam’s insistence on the importance of learning in general (Muslims are exhorted ‘to seek knowledge from the cradle to the grave’) and the high status accorded to women within Islamic society in particular.” The first Saudi government school for girls was built in 1964 and by the end of the 1990s there were girls’ schools in every part of the kingdom. In line with the Saudi policy of keeping the sexes apart, female education was administered separately until 2003 when it was incorporated into the normal functions of the education ministry. 12

Overall in the Arab countries, adult literacy increased from around 40 per cent in 1980 to 62 per cent in the early 2000s and school enrolment reached 60 per cent. This is certainly progress but it nevertheless means that 65 million Arabs remain illiterate and around ten million child...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Thinking inside the box

- 2. The gilded cage

- 3. States without citizens

- 4. The politics of God

- 5. Vitamin W

- 6. The urge to control

- 7. A sea of victims

- 8. Alien tomatoes

- 9. Escape from history

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index