![]()

1

Just Put One Foot in Front of the Other

In which we immerse ourselves in the oft-underestimated magnificence of getting around on our own two feet

Know thyself.

—ancient Greek aphorism

I wonder if you wouldn’t mind trying something out. If it’s safe and convenient, I’d like you to take a few steps. For more of a challenge, try turning a corner, or should the local lie of the land permit, go up or down a slope or a staircase. By all means, break into a run if you’re able and feeling sufficiently energetic. For most of us, unless hampered by injury, disease, or old age, all of this is so easy that we barely need to think about it. If we get the urge to go somewhere, we just go – rarely if ever do we need to devote any attention to the ins and outs of making the journey happen. But in taking our locomotory skills for granted like this, we seriously under-appreciate what is in fact a movement machine of dazzling sophistication. Our engineers have built spacecraft that can land on comets, and our computers have beaten grand masters at chess, but we have yet to see a robot whose movements come even close to the elegance, ease, and flexibility of human walking and running.

So, why not try those few steps again, but this time, think about exactly what you’re doing. How do you initiate and terminate movement? How do you avoid falling over, even when the ground is uneven? How do you turn, or shift up a gear into a run? Why, indeed, switch from walking to running at all? And how are you doing this all with such fantastic fuel efficiency – ten times that of top-of-the-range walking robots, such as Honda’s ASIMO?1 I realize, of course, that these are difficult questions to answer, for many of the processes that bring about self-propulsion happen beneath the level of our conscious awareness. But we cannot possibly begin our time-travelling, locomotory tour of life on Earth without first turning our enquiring eyes onto our own locomotion: we need to familiarize ourselves with the evolutionary destination before working out how we got here.

THE SIMPLE ANSWER

For something as commonplace as locomotion, it took us an awfully long time to even begin to understand how it works. Aristotle, a Greek philosopher we’ll meet properly in Chapter 4, was one of the first people to thoroughly ponder the problem. His observations and musings led him to conclude that all motions fall into one of two categories. The first – natural motions – are what an object or material does without being forced: what he deemed the ‘heavy elements’, water and earth, naturally fall; whereas the ‘light elements’, air and fire, rise. His second category – violent motions – covered those movements imposed on an object by an applied driving force, which would include locomotion. Take the force away, so he thought, and motion ceases. These ideas accord well with common sense: we need to push or pull a stationary object to shift it, and if we stop manhandling it, the object usually comes to a halt soon afterwards.

About 2,000 years later, Italian physicist-astronomer-philosopher Galileo realized that there was something deeply wrong with Aristotle’s thinking. While Galileo initially accepted that motions could be natural or violent, he reasoned that if an object’s natural tendency is to move directly towards the centre of the Earth, only movement in the exact opposite direction – that is, upwards – could be regarded as purely violent. What about objects moving horizontally? Galileo construed that those motions – directed neither away from nor towards the planet – must occupy a third category, which he called neutral motions. His great insight was to realize that once external impediments were removed, it would take only a small force to send an object into neutral motion, and once moving, it would take an impediment – friction, for instance – to stop it.

That may sound familiar. Galileo’s thoughts, encapsulated in his law of inertia, are essentially identical to the first law of motion formulated by mathematician-physicist Isaac Newton (1642–1727):

Every body continues in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it.2

That’s not to say that Newton’s thoughts on movement were simply a rehash of Galileo’s. In his second law of motion he extended the concept of inertia, stating that the acceleration (a) of an object caused by the application of a force (F) is in direct proportion to the magnitude of that force, but in inverse proportion to the object’s mass (m). In other words, F = ma. Furthermore, unlike Galileo, Newton realized that there was no physical basis for granting special status to natural motions: a fall, like any of Aristotle’s violent motions, must be caused by an applied force. Taken together, Newton’s insights made complete sense of Galileo’s famous free-fall experiment in which, as legend has it (some maintain that this was only a thought experiment), he dropped two balls of different mass from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. According to Aristotle, the heavier object should have fallen considerably faster, but in fact they struck the ground at nearly the same instant.3 The heavier ball’s greater mass meant that the force drawing it to the ground was larger, but greater mass also entails greater inertia, so the resulting acceleration was identical to that of the smaller ball. That constant acceleration (roughly 9.8 metres per second per second at sea level) was the result of the pull of gravity, and is now denoted g; the force – an object’s weight in the strict sense – can be found by multiplying that figure by the object’s mass.

The relationship between force, mass, and acceleration uncovered by Newton is clearly of great importance to locomotion. But where does the force that propels living things from place to place come from? This is where Newton’s third and final law of motion enters the picture. The third law is the really famous one, which states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction, but it’s also the least intuitive. It isn’t immediately obvious that when pushing on an object, the object simultaneously pushes back on you, but with hindsight it’s plain that this must be the case. If no force were pushing back, you wouldn’t be able to feel the object you were shoving. Similarly, when a falling ball bounces off the floor, there must be a force pointing upwards to enable the reversal of direction. Most critically as far as locomotion is concerned, the downward-pointing force of weight that we’re all subject to must be balanced by an equal and opposite force directed upwards, ultimately derived from the tiny forces acting between the atoms and molecules of the ground, or else we’d sink through the floor. That ground reaction force is the key to locomotion. Push back on the ground and it pushes forwards on you, accelerating you towards your chosen destination.

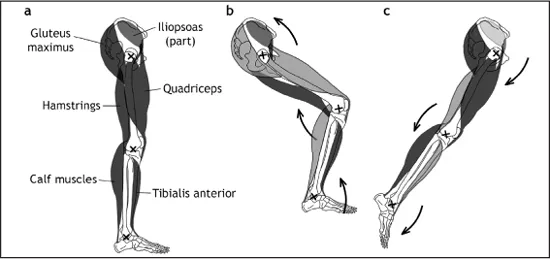

Our muscles are responsible for generating the push, though their action is necessarily indirect. That’s because muscles can only pull, so skeletal levers are required to convert the motion. The propulsive action of the human leg, for example, is brought about by its extensor muscles. The calf muscles, which attach to the heel bone via the Achilles tendon, swing the foot down and back about the ankle joint; the bulky quads, which run down the front and sides of the thigh to the tibia (the shinbone), straighten the leg at the knee joint; finally, the gluteus maximus (the buttock muscle), and the hamstrings, which run down the back of the thigh, swing the entire leg backwards about the hip joint. When the foot is planted on the ground (and as long as there’s sufficient friction between the two), the overall backward push of the leg brought about by the contraction of these muscles causes the forward acceleration of the body. That can’t continue indefinitely, of course, and because muscles can’t actively lengthen, the extensors must be reset by the contraction of their so-called antagonists – the flexor muscles – which each attach on the opposite side of a joint to its corresponding extensor. The principal leg flexors are: the tibialis anterior, which runs along the shin and inserts on top of the instep – this is largely responsible for raising the foot and thereby re-lengthening the calf muscles; the hamstrings, which bend the knee4 and stretch the quads; and the iliopsoas muscles, which run from the lower back and pelvis to the top of the femur (thigh bone) – they pull the leg forwards at the hip and stretch the buttock muscles. It goes without saying that the foot must be off the ground during these movements, otherwise we’d push forwards and end up back where we started. Fortunately, nature has provided us with a second leg, which can take over the support and propulsion duties during the reset.

1-1: The principal flexor and extensor muscles of the human leg (a) and a simplified picture of their actions (b, c). The tibialis anterior, hamstring group, and the iliopsoas group (of which only the lower, iliacus muscle is shown here, running from the inside of the pelvis to the femur) flex the ankle, knee, and hip, respectively (b), while the calf muscles, quadriceps group, and the gluteus maximus antagonize these actions by extending the same joints (c). When a muscle is activated (indicated by the darker tone in b, c), its relaxed antagonist (pale tone) is re-lengthened, thanks to its attachment on the opposite side of the relevant joint. Note that some of these muscles, such as the hamstrings, are bi-articular – they cross two joints – and so have alternative actions, depending on the activation state of other muscles or whether the leg is supporting any weight; the hamstrings, for instance, can extend the hip as well as flex the knee.

So, there we have it – the essential character of walking locomotion, with each leg alternately supporting the body during its stance phase and preparing for the next in its swing phase. Being a walk, there’s no unsupported aerial phase, so both legs are on the ground for at least 50 per cent of their respective strides (a stride encompasses one stance and one swing). This duty factor can get as high as 70 per cent in very slow walking, declining to about 55 per cent if we really need to get a move on but can’t quite bring ourselves to break into a run.

That’s all well and good, but the picture we’ve painted so far is pretty crude. Nothing we’ve seen yet couldn’t be applied to robots, with servos and motors taking the place of muscles, so we’ve little indication as to what makes our version so elegant and efficient by comparison. And there’s nothing to tell us what makes running different from walking, aside from the reduced duty factor that gives it its characteristic airborne stage. There must be more to it than that. Indeed there is, but uncovering the nuances of human locomotion was never going to be easy. Even the most leisurely of strolls involves moment-by-moment changes in the disposition of our limb segments that happen too fast for even the most dedicated observer to fully grasp, to say nothing of all the behind-the-scenes actions in the body that bring about these movements. What we needed was a way to slow down time and lift the bonnet on our locomotory engine.

THE TIME LORDS

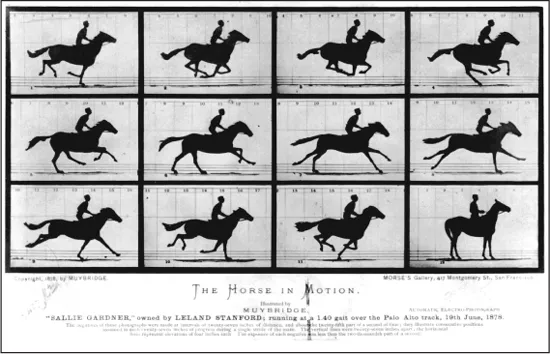

The man usually credited for ushering in the modern study of locomotion is the brilliant photographer Eadweard Muybridge. Born Edward Muggeridge near London in 1830, he immigrated as a young man to San Francisco, where he made something of a name for himself as a landscape photographer. His locomotory calling came in 1872, when railroad tycoon and former California governor Leland Stanford invited him to his stock farm in Palo Alto, supposedly to settle a $25,000 bet that a horse periodically becomes airborne when galloping.5 Muybridge was at first sceptical that photographic technology would be up to the task, but he gave it a go, and soon showed that, even when trotting, a horse does indeed lift all its hooves off the ground for a split second in each step cycle. His success was the turning point of his life: from that moment, capturing the movement of animals became Muybridge’s obsession. He worked intermittently at Palo Alto for several years, where he hatched an ingenious plan. He placed a set of cameras at regular intervals along a track, each rigged so that its shutter was activated by a trip wire stretched across the course. When Stanford’s horse Sallie Gardner galloped past, it therefore took a series of photographs of itself. The result was a breathtaking sequence of images that showed for the first time every intricate detail of an animal’s locomotory movements. Among other revelations, these pictures proved that the contentious aerial phase occurred not when the legs were at full stretch as many had supposed, but when the forelimbs and hindlimbs were at their closest approach.

1-2: Muybridge’s images of Leland Stanford’s horse ‘Sallie Gardner’.

Muybridge’s horse photographs won him widespread acclaim, and in 1884 he was offered a job at Pennsylvania University to apply his technique to a range of other animals, from baboons to lions. Significantly, he was also asked to photograph human movement, and he duly obliged, producing many sequences of men and women, not just walking and running, but jumping, boxing, somersaulting, dancing, even getting into bed. These works were beautiful and enthralling, and indeed remain so to this day. But in scientific terms, they really only scratched the surface. To work out exactly how we move, much more was needed than a simple series of freeze-frames. Fortunately, at about the same time that Muybridge began to uncover the secrets of horse movement, a Parisian physiologist was busy assembling the tools that would eventually fill in all the details he left out.

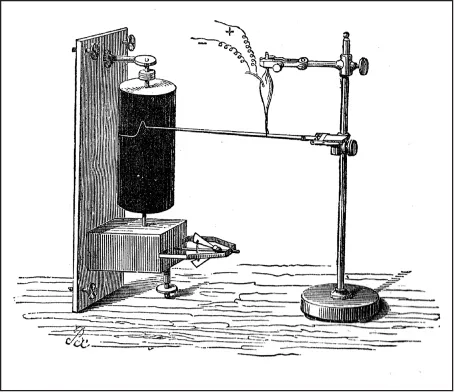

Étienne-Jules Marey was the true founding father of the science of locomotion. An exact contemporary of Muybridge (they were born and died mere weeks apart), he became obsessed with the task of, as he put it, translating the language of the body – uncovering and making apparent its moment-by-moment activities. To this end, Marey devised what he called his ‘graphical method’, which could turn all kinds of physiological movements, such as a person’s pulse, into readily comprehended readouts, by mechanically transmitting the motion to a stylus, using either a lever or a puff of air in a rubber tube. The stylus inscribed a line on a sheet of smoked paper that, importantly, was mounted on a steadily rotating cylindrical drum. The resulting readout thus captured the time course of the motion as well as its magnitude.

1-3: Marey’s graphical method: when the muscle contracts, the stylus is lifted, inscribing a curve on the smoked paper attached to the rotating drum. From Animal Mechanism (1874).

Marey milked his graphical method for all it was worth (once commenting that to undertake physiological investigations without it was like doing geography without maps) and it wasn’t long before his focus shifted from the most minute movements of the human body to the most obvious – the movements of locomotion. For his first project he set out to record the pattern of forces exerted by the feet when walking and running, which he did by mounting customized rubber soles onto his subject’s shoes, each containing a small air chamber that communicated with the recording apparatus via the usual rubber tube. Whenever the foot pushed on the ground, a puff of air was sent to the stylus, which deflected in proportion to the magnitude of the ground reaction force. Marey was also interested in how the timing of footfalls corresponded with the rise and fall of the body, so he mounted another device on the subject’s head, consisting of a small lump of lead attached to a lever. Given the lead’s high inertia, its vertical motions lagged behind those of the person below, so a trace of its relative displacement was presumed to give a fairly accurate representation of the up-and-down movements of the subject.

Marey’s technique worked wonderfully, and it wasn’t long before he’d extended his analysis to other animals, including horses.6 However, while his method told him about certain gross characteristics of an animal’s locomotory movements, he could find no way of reliably measuring how fast it or its limbs were moving. Then, in 1879, he saw Muybridge’s first photographic sequences and realized with delight that his prayers had been answered. He soon struck up a correspondence, and in 1881 invited the photographer to his home in Paris to give a public demonstration of his image sequences. These Muybridge displayed using his purpose-built zoopraxiscope – a device, made at Marey’s suggestion, which projected painted reproductions of his photographs in rapid sequence: it was, in effect, the world’s first movie projector. By all accounts, the guests were utterly enthralled – all, that is, except for the renowned painter and horse expert Anton Meissonier, who saw with horror that he’d been getting horse posture wrong for years.

Muybridge’s method of slowing down time presented a potential solution to Marey’s motion analysis problem, but there was a niggling issue. Because Muybridge’s cameras were triggered by the subject, the photographs represented arbitrary points in time, making an accurate calculation of the speed of the body or limbs impossible. Marey realized that if, instead of using multiple cameras, a single photographic plate was exposed multiple times at a known rate, all the necessary information would be available in one image. So, that’s what he did. His first multiple-exposure photographs were promising, but if the movements were too slow, the successive freeze-frames were confusingly superimposed. Marey got around this problem, for humans at least, by getting his s...