![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE ANARCHIC ECONOMY

Above, far above the prejudices and passions of men soar the laws of nature. Eternal and immutable, they are the expression of the creative power; they represent what is, what must be, what otherwise could not be. Man can come to understand them: he is incapable of changing them.

Vilfredo Pareto (1897)

Spread the truth – the laws of economics are like the laws of engineering. One set of laws works everywhere.

Lawrence Summers (1991)

Economics gains its credibility from its association with hard sciences like physics and mathematics. But is it really possible to describe the economy in terms of mathematical laws, as economists including Larry Summers – former economics advisor to President Obama – claim? Isaac Newton didn’t think so. As he noted in 1721, after losing most of his fortune in the collapse of the South Sea bubble: ‘I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.’

To see whether the economy is law-bound or anarchic, bear with me first for a little ancient history. It turns out that many of the ideas that form the basis of modern economics have roots that stretch back to the beginnings of Western civilisation. That’s one reason why they are proving so hard to dislodge.

The first economic forecaster, in the Western tradition, was probably the oracle at Delphi in ancient Greece. The most successful forecasting operation of all time, it lasted for almost a thousand years, beginning in the 8th century BC. The predictions were made by a woman, known as the Pythia, who was chosen from the local population as a channel for the god Apollo. Her predictions were often vague or even two-sided and therefore hard to falsify, which perhaps explains how the oracle managed to persist for such a long time (rather like Alan Greenspan).

Our tradition of numerical prediction can be said to have begun with Pythagoras. He was named after the Pythia, who in one of her more famous moments of insight had predicted his birth. (She told a gem-engraver, who was actually looking for business advice, that his wife would give birth to a boy ‘unsurpassed in beauty and wisdom’. This was a surprise, especially because no one, including the wife, knew she was pregnant.)

As a young man, Pythagoras travelled the world, learning from sages and mystics, before settling in Crotona, southern Italy, where he set up what amounted to a pseudo-religious cult that worshipped number. His followers believed that he was a demi-god descended directly from Apollo, with superhuman powers such as the ability to dart into the future. Joining his inner circle required great commitment: candidates had to give up all material possessions, become vegetarian ascetics, and study under a vow of silence for five years.

The Pythagoreans believed that number was the basis for the structure of the universe, and gave each number a special, almost magical significance. They are credited with many mathematical discoveries, including the famous theorem about right-angled triangles and the square of the hypotenuse which we are all exposed to at school. However, their major insight, which backed up their idea that number underlay the structure of the universe, was actually about music.

If you pluck the string of a guitar, then fret it exactly halfway up and pluck it again, the two notes will differ by an octave. The Pythagoreans discovered that the notes that harmonise well together are all related by the same kind of simple mathematical ratio. This was an astonishing insight, because if music, which was considered the most expressive and mysterious of art forms, was governed by simple mathematical laws, then it followed that all kinds of other things were also governed by number. As John Burnet wrote in Early Greek Philosophy: ‘It is not too much to say that Greek philosophy was henceforward to be dominated by the notion of the perfectly tuned string.’1 (And modern physics; see string theory.)

The Pythagoreans believed that the entire cosmos (a word coined by Pythagoras) produced a kind of tune, the music of the spheres, which could be heard by Pythagoras but not by ordinary mortals. And their interest in number was not purely theoretical or spiritual. They developed techniques for numerical prediction, which remained secret to the uninitiated, and it is also believed that Pythagoras was involved with the design and production of the first coins to appear in his area. Money is a way of assigning numbers to things, so it obviously fit with the Pythagorean philosophy that ‘number is all’.

Rational mechanics

If the cosmos was based on number, then it could be predicted using mathematics. The ancient Greeks developed highly complex models that could simulate quite accurately the motion of the stars, moon and planets across the sky. They assumed that the heavenly bodies moved in circles, which were considered to be the most perfect and symmetrical of forms; and also that the circles were centred on the earth. Making this work required some fancy mathematics – it led to the invention of trigonometry – and a lot of circles. The Aristotelian version, for example, incorporated some 55 nested spheres. The final model by Ptolemy used epicycles, so that planets would go around a small circle that in turn was circling the earth.

The main application of these models was astrology. For centuries astronomy and astrology were seen as two branches of the same science. In order for astrologers to make predictions, they needed to know the positions of the celestial bodies at different times, which could be determined by consulting the model. The Ptolemaic model was so successful in this respect that it was adopted by the church, and remained almost unquestioned until the Renaissance.

Classical astronomy was finally overturned when Isaac Newton combined Kepler’s theory of planetary motion with Galileo’s study of the motion of falling objects, to derive his three laws of motion and the law of gravity. Newton’s insight that the force that made an apple fall to the ground, and the force that propelled the moon around the earth, were one and the same thing, was as remarkable as the Pythagorean insight that music is governed by number. In fact Newton was a great Pythagorean, and believed Pythagoras knew the law of gravity but had kept it secret.

Newton held that matter was made up of ‘solid, massy, hard, impenetrable, movable particles’, and his laws of motion described what he called a ‘rational mechanics’ that governed their behaviour. It followed, then, that the motion of anything, from a cannonball to a ray of light, could be predicted using mechanics. His work therefore served as a blueprint for numerical prediction – reduce a system to its fundamental components, discover the physical laws that rule them, express as mathematical equations, and solve. Scientists from all fields, from electromagnetism to chemistry to geology, immediately adopted the Newtonian approach, to enormously powerful effect. You can hear the whisper coming from the Pythagoreans: ‘Spread the truth – one set of laws works everywhere.’

Rational economics

Among those to hear the whisper, if somewhat belatedly, were the new group of people calling themselves economists in the late 19th century. If Newtonian mechanics was proving so successful in other areas like physics and engineering, maybe it could also be applied to the flow of trade.

The theory they developed is known as neoclassical economics. Today it still forms the basis of orthodox theory, and makes up the core curriculum taught to future economists and business leaders in universities and business schools around the world.2 As a set of ideas, it might be the most powerful in modern history.

Neoclassical economics is based on an explicit comparison with Newtonian physics. Just as Newton believed that matter is made up of minute particles that bump off one another but are otherwise unchanged, so neoclassical theory assumes that the economy is made up of unconnected individuals who interact by exchanging goods and services and money but are otherwise unchanged. Their behaviour can be predicted using economic laws, the human analogue of the laws that govern the cosmos.

To calculate the motions of the economy, one must determine the forces that make it move around. The neoclassical economists based their mechanics on the idea of utility, which the philosopher Jeremy Bentham described in his ‘hedonic calculus’ as the sum of pleasure minus pain. For example, if an apple gives you three units of pleasure, and paying for it gives you only two units of pain, then purchasing the apple will leave you one utility unit (sometimes called a util) in profit.

Leaving aside for a moment what units of measurement a util is expressed in, an obvious problem is that different people will assign different utility values to objects such as apples. The early neoclassical economists got around this by arguing that all that counted was the average utility. It was then possible to use utility theory to derive economic laws. As William Stanley Jevons put it in his 1871 book Theory of Political Economy, these laws were to be considered ‘as sure and demonstrative as that of kinematics or statics, nay, almost as self-evident as are the elements of Euclid, when the real meaning of the formulae is fully seized’.

Thus was born the economyth that the economy can be accurately described by economic laws; which to quote the English economist Lionel Robbins – who famously defined economics in 1932 as the science of scarcity – were ‘as universal as the laws of mathematics or mechanics’.3 Chief among these universal laws were what Jevons called the ‘unquestionable truth of the Laws of Supply and Demand’.

Imaginary lines

If economics has an equivalent of Newton’s law of gravity, it is the law of supply and demand. Economist Brad DeLong calls it the ‘one real law of economics’.4 According to Arnold Kling, ‘the law of supply and demand always operates, even though markets have different institutional structures’.5 Christopher Ragan and Richard Lipsey state in a textbook that ‘The term “law” in science is used to describe a theory that has stood up to substantial testing’; and in this case ‘the predicted behaviour occurs sufficiently often that economists continue to have confidence in the underlying theory’.6 Rather like the law of gravity, ‘The theory of the determination of price by demand and supply is beautiful in its simplicity’ but is ‘powerful in its wide range of applications’.

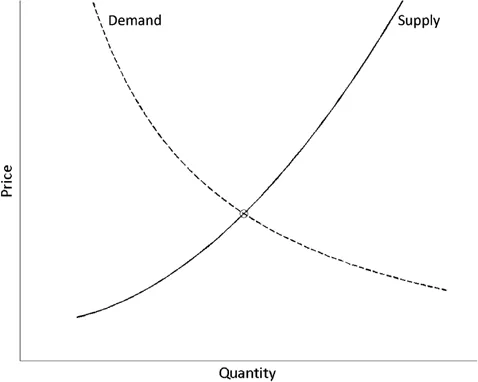

The law is illustrated in Figure 1, which is a version of a graph first published in an 1870 essay by Fleeming Jenkin. It has since become the most famous figure in economics, and is taught at every undergraduate economics class. The figure shows two curving lines, which describe how price is related to supply and demand. When price is low, supply is low as well, because producers have little incentive to enter the market; but when price is high, supply also increases (solid line). Conversely, demand is lower at high prices because fewer consumers are willing to pay that much (dashed line).

The point where the two lines cross gives the unique price at which supply and demand are in perfect balance. Neoclassical economists claimed that in a competitive market prices would be driven to this point, which is optimal in the sense that there is no under- or over-supply, so resources are optimally allocated. Furthermore, the price would represent a stable equilibrium. The market was therefore a machine for optimising utility.

Figure 1. The law of supply and demand. The solid line shows supply, which increases with price. The dashed line shows demand, which decreases with price. The intersection of the two lines represents the point where supply and demand are in balance.

For example, suppose the equilibrium price for a house is 500,000 (currency units of your choice), but for some reason (perhaps recent volatility) the market is not currently at equilibrium and the price is instead 550,000. The quantity supplied at this price would be higher than the quantity demanded, so to entice consumers the sellers would have to reduce the price until it reached the equilibrium level where the quantity demanded matched the quantity supplied. The net effect would be to pull prices down to their resting place, as sure as the force of gravity. Conversely, if prices were too low, then supply would drop, demand would increase, and prices would bob back up again.

However, if demand were to increase for some structural reason, such as population growth, then t...