![]()

Living and bleeding in London

Ah! my poor dear child, the truth is, that in London it is always a sickly season. Nobody is healthy in London, nobody can be.

Jane Austen, 1816

Emma

JAMES PARKINSON was born into the Enlightenment on Friday 11 April 1755. He grew up alongside the Industrial Revolution and died a Romantic on Tuesday 21 December, 1824. His life spanned a period of intellectual turbulence and political upheaval, burgeoning science and technology; they were dramatic and exciting times to be alive. Among his contemporaries were Mozart and Marie Antoinette, the chemists Joseph Priestley and Humphry Davy, the surgeon brothers John and William Hunter, Edward Jenner who discovered the smallpox vaccine, the poet William Wordsworth, the painter William Turner, and the geologist William Smith.1

James was the second of six children,* only three of whom – James and two younger sisters, Margaret and Mary – survived to adulthood; the three others died within their first five years.2

There is little known about his mother, besides the fact that she was called Mary and that burial records say she died on 6 April 1811 aged 90 – a grand age for someone of those times. Fortunately, because it was common in the eighteenth century for parents to choose names for their children that honoured their relatives – indeed, to avoid insulting anyone there was even a convention for the order in which the relatives were chosen – it becomes possible to identify that she was a Mary Sedgwick, baptised 16 April 1721 in Rotherhithe, Surrey.3 As people were generally buried less than a week after their death, it seems likely that Mary actually died a few days short of her 90th birthday.

Attempts to determine the birthdate and birthplace of Parkinson’s father, John, have met with less success.4 Furthermore, there is no record of any marriage between a John Parkinson and a Mary Sedgwick (or indeed any Mary at all) between 1750 and 1753 – the most likely period for a marriage to have taken place, given the arrival of the couple’s first child in November 1753.

Nor has any portrait of James Parkinson yet been found, although the internet boasts two different photos supposed to be of him. Unfortunately, since photography was not invented until 1838, fourteen years after Parkinson died, a photograph of him cannot possibly exist. The photographs in question are of two different James Parkinsons. One was a dentist who lived 1815–1895. The image of him was clipped from a group photo taken in 1872 of the membership of the British Dental Association. The man in the other photo, who has a big bushy beard, is a James Cumine Parkinson (1832–1887), an itinerant Irishmen who ended up as a lighthouse keeper off the coast of Tasmania.5

We are therefore left to imagine Parkinson’s physical appearance, and to help us do that we have a brief verbal description written by his young friend, Gideon Mantell.6 Mantell would have been in his early twenties when he knew Parkinson, then in his late fifties. He tells us: ‘Mr Parkinson was rather below middle stature, with an energetic intellect, and pleasing expression of countenance, and of mild and courteous manner; readily imparting information, either on his favourite science [fossils], or on professional subjects’.7 Like Parkinson, Mantell was a medical practitioner with a passion for fossils.

Another man with whom ‘our’ James Parkinson is often confused was an older James Parkinson (1730–1813) whose wife purchased the winning lottery ticket for the disposal of Sir Ashton Lever’s exotic natural history collection. Noted for the artefacts it contained from the voyages of Captain Cook, formation of the collection had bankrupted Lever. In order to recover some of the money he obtained an Act of Parliament which allowed him to sell the collection by lottery, but at a guinea each he only sold 8,000 tickets, when he had hoped to sell 36,000. The lucky James Parkinson who acquired the collection spent nearly two decades trying to make a success of Lever’s museum, eventually putting it up for auction in 1806.8 ‘Our’ James Parkinson was present at the auction and purchased a number of items.

The James Parkinson with whom this book is concerned lived all his life in Hoxton, a village located a mile north of Bishopsgate, one of the narrow medieval gates of the City of London,9 within the parish of St Leonard’s Shoreditch in the county of Middlesex. In a survey of 1735 the total number of houses in Hoxton was 503,10 but it was fast becoming urbanised as London rapidly expanded northwards during the Industrial Revolution. In 1700, London had a population of just under 600,000; a century later it had reached over a million and was the largest city in the world.11 Today Hoxton can be found on the enlarged maps which represent the very heart of London in its A–Z of streets. These pages cover an area of less than three miles across from north to south, and five miles east to west, which is larger than the whole of London was in 1750.

As the city became more and more prosperous during the eighteenth century this was reflected in Hoxton where the population grew rapidly. There was a phenomenal rise in trade in the docks and in business generally, which fed an increase in employment and attracted agricultural workers out of the fields and into the metropolis. Residential areas in the city were taken over for business purposes, and as houses were demolished to make room for factories, warehouses and offices, displaced residents and incomers were forced to find homes beyond the City walls in places like Hoxton. The City Fathers, wealthy merchants and businessmen who could afford a horse and carriage, were able to live where they chose and opted for country seats or sophisticated squares. ‘Oh how I long to be transported to the dear regions of Grosvenor Square!’ sighs Miss Sterling in George Colman’s popular comedy The Clandestine Marriage.12 Such Georgian squares launched a new style of town-house: the narrow-fronted terrace; and vertical living became both a novelty and a necessity as space became scarce and land more expensive. Terraces were often set around a square to compensate for the fact that the houses themselves had little land of their own.

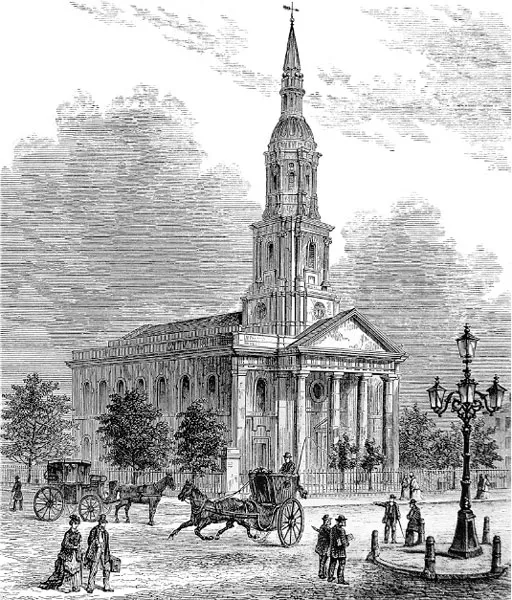

The Parkinsons lived at No. 1 Hoxton Square, a three-storey terraced town house constructed between 1683 and 1720 around a large square of more than half an acre.13 The house was built of bricks since there was a requirement to use fire-resistant materials following the Great Fire of London. In almost every room there were large, open fireplaces carved in an elaborate design. Some of the rooms were connected by elegant arches and many had deep panelling on the walls with pastel colours painted on the ceilings. The most important rooms, impressively large, were on the first floor where long sash windows looked out over the square which formed the focus of this elegant community. But only the residents were able to enjoy its privileges, each householder owning a key to the garden’s delights. From these windows the Parkinsons could see the spire of St Leonard’s Church, a fine example of Georgian ecclesiastical architecture.14 There James was baptised on 29 April 1755, married on 17 May 1781, and buried on 29 December 1824. His grave can no longer be found in the graveyard; it is probably in the crypt along with hundreds of others that were moved there around the beginning of the twentieth century so that the road could be widened.15 However, a badly deteriorating plaque dedicated to the memory of his father, John Parkinson, can still be seen on the churchyard wall. John had been the much-loved apothecary surgeon in Hoxton for more than 40 years, fulfilling a position in society similar to that of today’s GP. The twelve-line inscription probably once told us who had erected the plaque and why, but it is now illegible. Another plaque inside the church, put up in 1955, celebrates the bicentenary of James Parkinson’s birth.

St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch, as James Parkinson would have known it.

The original house at No. 1 Hoxton Square was still standing 100 years ago, although by then it was derelict.16 At that time it had a smaller two-storey building on the back with a central door that opened on to a side street. This door had probably been the entrance to the apothecary shop where the Parkinsons made up and dispensed medications. Behind that was yet another small building which may have been added at a later date to house Parkinson’s ever-growing collection of fossils. Side streets provided access to shops and services, but beyond these, when James was born in 1755, were open fields, market and flower gardens, orchards, and grand old mansions standing in extensive grounds.

Despite the apparent grandeur of Hoxton Square, sanitary conditions were appalling. Household waste fed into open ditches that flowed down the centre of the streets, since Hoxton had no sewer. The ditches discharged into a tributary of the Walbrook river that ran through Shoreditch; the Walbrook, now one of London’s several subterranean rivers, eventually released Hoxton’s waste into the heavily polluted Thames. At night there would be commodes in the bedrooms, while in most dining rooms there was a set of chamber pots hidden behind curtains or in a cupboard for the relief of gentlemen after dinner. These were generally emptied straight into the street, although one of the greatest causes of pollution of London’s waterways occurred with the introduction of the improved water-closet in the 1770s. Many of these overhung streams – the earliest and simplest way of disposing of the contents. The house itself probably had piped water, drawn from the Thames and supplied via pipes of elm wood laid under the main streets, although the source of that water was highly questionable and the contents virtually undrinkable, as one Scottish visitor lamented:

If I would drink water, I must quaff the mawkish contents of an open aqueduct, exposed to all manner of defilement; or swallow that which comes from the river Thames, impregnated with all the filth of London and Westminster – human excrement is the least offensive part.17

Rain water too, ‘being, from the soot and dirt on the roofs of houses etc, loaded with impurities’ was rarely used, except for the meanest domestic purposes.18

Originally the nine water companies in London were each allocated a different region of the City, but when ‘healthy competition’ was introduced, the result was cut-throat. Each company established separate reservoirs and pumping stations, tore up roads and pavements in order to lay competing sets of pipes, canvassed each other’s customers and made wild promises they had no hope of keeping, in order to steal a march on the competition. After a few years of this mayhem, the companies again agreed to divide the City between them and withdrew to their allocated districts, but then a cartel formed which allowed charges to rise steeply in order to pay for the costs recklessly incurred during the previous years of warfare. It’s a familiar story.

The primary sources of lighting were candles and oil lanterns, and the only source of heat was invariably an open fireplace burning coal in a cast iron basket, so not the least drawback to living in the City was the constant pall of thick smoke that hung around its shoulders. The travel writer Pierre-Jean Grosley complained that winter in London lasted eight months and that the smoke, ‘rolling in a thick, heavy atmosphere, forms a cloud which envelops London like a mantle’.19 The fallout from this cloud, soot, covered the buildings and anything left outside, even the horses. Aside from the burning of coal in the grates of every household in town, soot was generated by the thousand-and-one small businesses that choked the City’s back streets – the smithies, the potteries, the brewing, baking and boiling trades, and the myriad other enterprises. And the pall didn’t stay within the City walls: ‘the smoke of fossil coals forms an atmosphere, perceivable for many miles’, grumbled another tourist;20 so it can be assumed that even the Parkinsons’ fashionable residence, a mile outside the City walls, was covered in grime.

Several good schools existed in Hoxton and the surrounding area and James probably attended one of these, as his published advice on how to prepare young men for the medical profession refers to the need for them to have had a ‘common school education’.21 By the mid-eighteenth century the syllabus of many Middlesex schools included Latin, Greek and French, arithmetic, book-keeping, ‘all branches of the mathematics’, and the ‘use of globes’.22 Natural philosophy, the precursor to modern science, was introduced on to the curriculum of some private schools around this time, and since Parkinson considered natural philosophy an essential background for medical students, it seems likely he studied the subject at school. In addition to the languages already mentioned, he was able to read German and Italian, and he also used shorthand throughout his life, which he says he learnt as a boy. These were usually subjects for which extra fees had to be paid, suggesting his schooling was of a higher standard than a ‘common school education’.

Hoxton, renowned for its ‘dissenting’ ambience, offered university-level educational facilities in the form of the Nonconformist Hoxton Academy, which moved into Hoxton Square in 1764.23 Nonconformists advocated religious freedom and opposed State interference in religious matters, but as these beliefs did not ‘conform’ to the views of the established Anglican Church, nonconformists were restricted from many spheres of public life. They were also barred from various forms of education which compelled them to fund their own academies. The Hoxton Academy provided a university education for young men who were prevented from attending Oxford or Cambridge because of their dissenting views, its presence giving the Square an almost collegiate air. Although James is unlikely to have attended the Academy, since he and his family were members of the Anglican congregation at St Leonard’s, the Parkinsons undoubtedly knew many of its tutors, attending them and their students when they were ...