- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The 50 Greatest Churches and Cathedrals

About this book

Cathedrals and great churches are among the most iconic sights of the world's towns and cities.Visible from miles around, the cathedrals of Canterbury, St Paul's, Chartres and St Stephen's in Vienna dominate their skylines. Others surprise by their statistics: Salisbury has Britain's tallest spire, Wells the largest display of medieval sculptures in the world, while King's College Chapel in Cambridge boasts the largest fan vaulting in existence. Not all are ancient: Dresden's reconstructed Frauenkirche opened in 2005 and Gaudi's masterpiece in Barcelona is still under construction.Award-winning travel writer Sue Dobson gives us a highly personal tour of their highlights.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The 50 Greatest Churches and Cathedrals by Sue Dobson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Travel. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

UNITED KINGDOM and IRELAND

– ENGLAND –

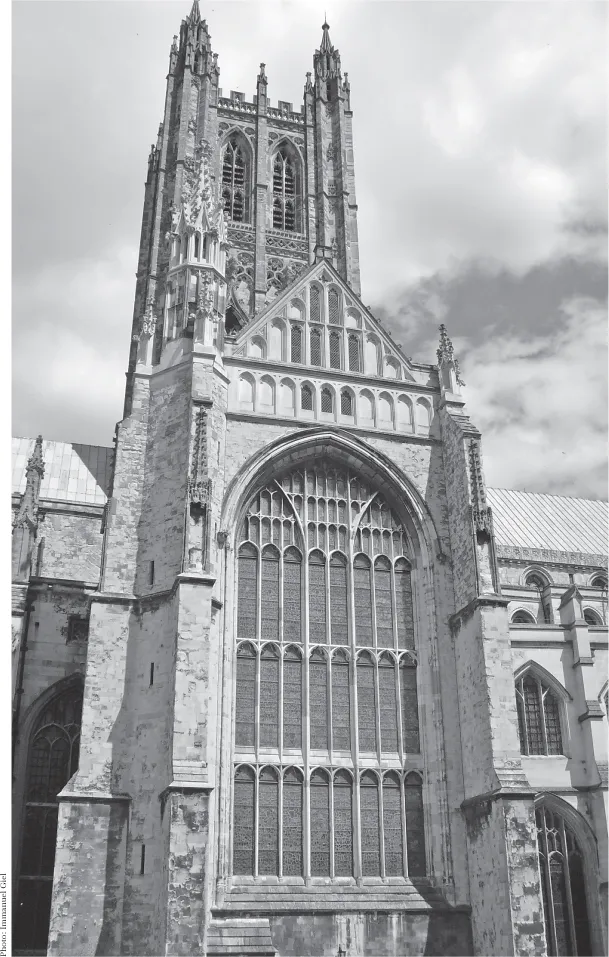

CHURCH OF CHRIST, CANTERBURY

The Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and shrine to the rebirth of Christianity in England, is host to more than a million visitors a year. Every hour, on the hour, they are asked to be still and join in a prayer – a reminder that, spectacular though the building is, Canterbury Cathedral is very much a working church.

Huge and intricate, overpowering and dramatic, it is a multi-layered cathedral, each level reached by steps shaped by centuries of pilgrim feet. It was the brutal murder, at an altar in his own cathedral, of Archbishop Thomas Becket by four of King Henry II’s knights on 29 December 1170 and accounts of miraculous healing immediately after his death, that brought the Christian world to its doors in the Middle Ages. Becket’s was one of the holiest shrines in all Europe and pilgrimages continue to this day.

Founded in 597, it was rebuilt in 1070 and then largely rebuilt and extended in creamy-white Caen stone in 1178. A devastating fire four years earlier had demolished most of the previous cathedral, though the vast and atmospheric 11th-century crypt with its rounded arches and decorated columns, naves, aisles and side chapels, survives to present us with some of the finest Norman stone carvings on pier capitals in England.

They range from geometric to floral to entire stories that are often comical or violent. Look for animal musicians and winged beasts, rams’ heads, knights doing battle and a rather appealing lion. The 12th-century wall paintings in the crypt’s St Gabriel’s Chapel, which include the Archangel Gabriel announcing the birth of John the Baptist to the elderly Zacharias, are the oldest known Christian paintings in the country.

Long, light, tall and graceful, the nave has slim, soaring columns rising to delicate vaulted arches and gilt roof bosses. Looking back you see the glorious west window, its stained glass dating back 800 years; ahead of you, a wide flight of steps leads up to the richly carved, 15th-century stone pulpitum (choir screen) that separates the nave from the choir. Within its niches are original effigies of six English kings that somehow escaped the swords of the Puritans who, during the Civil War of the 1640s, destroyed the accompanying statues of the twelve Apostles during their rampage of destruction through the cathedral. They even stabled their horses in the nave.

Through the screen’s archway you get an inspirational view up to the high altar. Stand under the great Bell Harry Tower, and marvel at the stupendous fan vaulting high above you.

From the north-west transept, steps lead down to the Martyrdom Chapel. The site of Becket’s murder is marked with a simple altar and a dramatic modern sculpture of jagged swords. Nearby, the circular Corona Chapel, built to house the skull fragment of the crown of the head of St Thomas Becket, sliced off by the sword of one of the attackers, is dedicated to saints and martyrs of our own times.

The powerful choir is Early French Gothic in style, built between 1175 and 1185 and the first major example of Gothic architecture in Britain. The architect, master mason William (Guillaume) de Sens, was badly injured when he fell from scaffolding while inspecting the central roof boss – depicting a lamb and flag in blue and gold, a symbol of the Resurrection – in 1178. His assistant, William the Englishman, continued and completed the work, including the graceful Trinity Chapel behind the high altar.

The Trinity Chapel is where Becket’s relics once rested in a magnificent gold and jewel-encrusted shrine, destroyed in 1538 on the orders of King Henry VIII. Cart loads of treasure boosted the royal coffers – a large ruby, given by the King of France, is now part of the crown jewels in the Tower of London.

Two years later, as part of the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry closed down the Benedictine monastery that had surrounded the cathedral since the 10th century. Today a solitary burning candle marks the site of the shrine; the flooring, with its beautiful Italian marble paving, survives and dates from 1220.

The chapel houses the tomb and superb bronze chain mailed effigy of Edward the Black Prince, eldest son of King Edward III and father of King Richard II, who died in 1376. His military victories, especially over the French in the Battles of Crécy and Poitiers, made him a popular figure at home (though not, unsurprisingly, in France, where he was considered an evil invader and occupier).

Opposite, lies his nephew, King Henry IV (d.1413), the only king to be buried in Canterbury Cathedral, and his wife, Joan of Navarre, Queen of England. Finely detailed alabaster effigies show them side by side, crowned in gold.

Trinity Chapel is also where you’ll find St Augustine’s Chair, the ceremonial enthronement chair of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Made from one piece of Petworth marble, it dates from the early 13th century.

Pilgrims to the shrine would have gazed in awe at the luminous stained glass of brilliant hue that portrays miracles attributed to the saint. Roundels in the aptly named Miracle Windows in the ambulatory begin with Becket at prayer and then a storyboard of scenes unfolds to tell of individuals who were cured of maladies from leprosy to blindness and myriad disabilities. Dating from the early 13th century, the colours are extraordinary – intense blue, striking reds, golden yellows, sharp greens – and the figures recognisably lifelike, studied yet full of movement.

Canterbury has a wealth of medieval stained glass. The colours are deep and vibrant and every image tells a story, whether biblical or of the cathedral’s own history. Look especially for the Bible and the Miracle windows, but all of it will stop you in your tracks.

The west window is also known as the genealogy window for it contains images of early English kings and royal coats of arms, archbishops and, in the tracery lights, an array of apostles and prophets, all glass from the late 12th or early 13th centuries. The oldest (c.1174), Adam Delving in the Garden of Eden, showing Adam as a peasant tilling the soil, is in the bottom row.

In the north choir aisle, two 12th-century Bible windows tell Old and New Testament stories, from Noah releasing the dove to St Peter preaching, the Magi following the star to the parable of the sower and Christ’s miracles, including the Marriage at Cana and the miraculous draught of fish.

When Pope Gregory sent St Augustine and his monks from Rome in 597, to restore the Christian faith to the Saxon English, they landed in Thanet and were welcomed by King Ethelbert (who would soon be baptised by Augustine) and his French Christian wife, Queen Bertha. Augustine was the first Archbishop of Canterbury.

A short walk from the cathedral lie the ruins of St Augustine’s Abbey, founded in 598. The abbey, the cathedral and St Martin’s church are a World Heritage Site and are linked by Queen Bertha’s Walk. St Martin’s, believed to date back to Roman times and the oldest church in continuous use in England, is where St Augustine came to worship before he established his monastery.

The cathedral’s late medieval cloisters and large chapter house are remnants of the Benedictine monastic buildings. Originally set out by Archbishop Lanfranc in the 11th century and rebuilt in the early 15th, with their heavily ribbed lierne vaulted ceiling they are fine examples of the Perpendicular style – no surprise perhaps because they were remodelled by Stephen Lote, a pupil of the royal master mason Henry Yevele, who created the stunning nave. Roof bosses and heraldic shields tell of people who contributed to the rebuilding of the cathedral back in the 12th century and modern stained glass, installed in 2014, commemorates modern benefactors to the conservation of the building’s fabric.

Lanfranc also built the rectangular chapter house with stone seating for the monks around the walls and a raised chair for the prior. Made from Irish oak, the beautiful early 15th-century wagon vaulted ceiling was given by Prior Chillenden, as were the stained glass windows that depict important people in the history of the cathedral.

The top row of the east window shows Queen Bertha, St Augustine and King Ethelbert. King Henry VIII appears second left on the bottom row. The west window depicts scenes from the history of the cathedral, including the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket, the penance of King Henry II and the move of Becket’s bones to his shrine in 1220.

Entry to the cathedral and its precincts is via the impressive, turreted and highly decorated Christ Church Gate, one of the last parts of the monastic buildings to be erected before the Dissolution. Ironically, it may have been built to commemorate the marriage of Prince Arthur, elder brother of King Henry VIII, to Katharine of Aragon in 1502. (The young prince died a few months later and Henry went on to marry Katharine himself.)

Emerge from the gateway and take time to stand and stare. Of the cathedral’s three pinnacled towers, the central Bell Harry tower rises supreme. It dates from between 1493 and 1503, is 72 metres (235 feet) high and is named after the original bell given by Prior Henry. Inside, the exquisite fan vault interior of the tower is one of the most glorious sights of this most memorable of cathedrals.

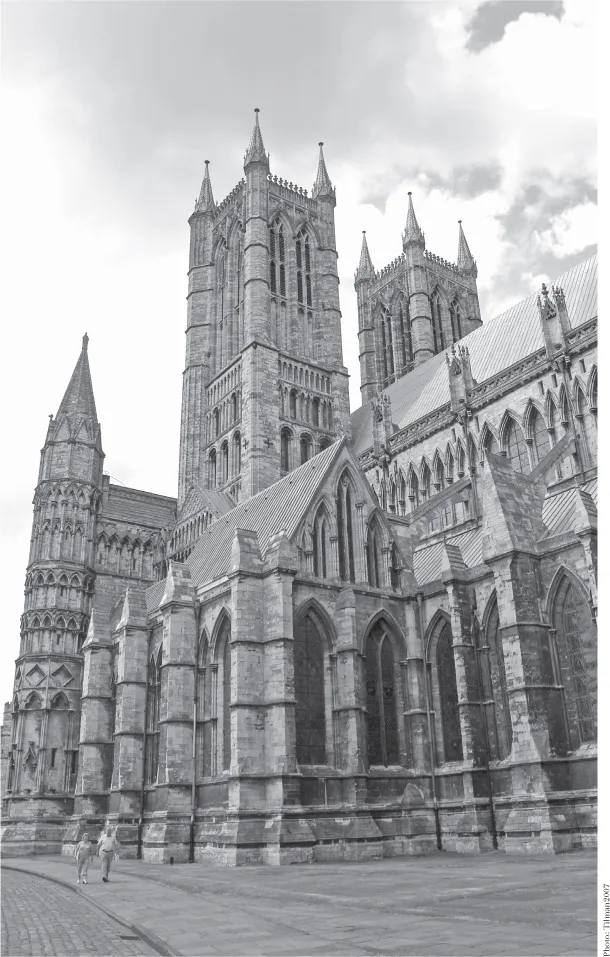

CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, LINCOLN

Crowning the city, its three vast towers visible for miles, Lincoln’s hilltop cathedral is one of the finest medieval buildings in Europe. It is huge – in terms of floor area, among English cathedrals only St Paul’s in London (page 43) and York Minster (page 34) are bigger – and it presents a dramatic and elegant face to the world.

The 14th-century towers, delicate, lacy and topped with sky-piercing pinnacles, rise up behind the west front’s 13th-century screen with its rows of Norman niches, Early Gothic blind arcading and handsome Norman doors.

The towers today are an impressive height, but when the central tower collapsed in 1237 its replacement was topped with a spire, reputedly making Lincoln’s cathedral the tallest man-made structure in the world, topping even Egypt’s Great Pyramid at Giza. It held that record for 238 years, until the 160-metre (525-foot)-spire blew down in a raging storm in 1548 and wasn’t replaced.

William the Conqueror ordered a cathedral to be built on the hill in Lincoln, sited next to his castle for security, and sent Bishop Remigius to supervise it. Constructed of locally quarried Lincolnshire limestone and consecrated in 1092, it commanded a vast diocese that stretched from the Humber estuary in the north to the River Thames in the south, spanning nine counties and encompassing several notable and wealthy monasteries.

After a devastating earthquake in 1185, Hugh of Avalon, a Carthusian monk of character, began the rebuilding of the cathedral, greatly enlarging it in the Early Gothic style, incorporating pointed arches, ribbed vaults, lancet windows and flying buttresses. Consecrated Bishop of Lincoln in 1186, he died in 1200 and was canonised in 1220 – in good time for the completion of the new cathedral, which saw pilgrims flocking to his shrine.

The long nave is soaring and lyrical, a space of beauty and light – especially when sunshine pours through the fine Victorian stained glass and dapples the limestone floor and piers with patterns of rich colour. Graceful arched stone ribs draw the eye heavenwards.

At the nave’s end, the elaborate choir screen is a tour de force of early 14th-century carving, alive with beasts, heads and fantasy creatures among leaves and flowers.

The Bishop’s Eye floods the great transept with light from on high. A magnificent circular rose window of precious medieval stained glass, its graceful tracery of leaves encases the glass with softly curving lines. Facing it on the north side, the earlier (13th-century) Dean’s Eye rose window has four circles surrounded by sixteen smaller ones, with some of its original Last Judgement narrative still discernible.

Ornate 13th-century doorways lead to the choir aisles – look for dragons hiding behind foliage and the sword-bearing men seeking them out – and bring you towards a forest of exquisite wood and stone carving of heart-stopping delicacy.

The angels, carved on the choir desks around 1370, play harps, pipes and a drum; etched in gold above the canopied and pinnacled choir stalls with their secretive misericords are the first lines of psalms each canon was appointed to read.

The Treasury is located in the north side choir aisle. It was the first open Treasury in an English cathedral and as well as Lincoln’s own silverware it contains other sacred pieces from churches around the diocese. The highlight is a medieval chalice hallmarked 1489.

Behind the high altar, the Gothic Angel Choir has a feast of stone carving and impressive stained glass windows. It was created to hold the shrine of St Hugh, whose following was so great that the cathedral had to be extended 80 years after his death to accommodate all the pilgrims. King Edward I and Queen Eleanor were among the great and the good that were there to see his body translated to the site prepared for him.

The infamous Lincoln imp has his place here among the host of presiding angels. The legend goes that the mischievous imp caused mayhem in the cathedral and when he started throwing rocks at the angels they turned him to stone. He may be quite difficult to spot high up in his spandrel, but his image has long been a symbol of the city.

The tomb of King Edward I’s beloved wife Eleanor of Castile, who died near Lincoln in 1290, contains the viscera from her...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- The 50 Greatest Churches and Cathedrals of the World

- United Kingdom and Ireland

- Ireland

- Scotland

- Wales

- Europe

- Belgium

- Czech Republic

- Finland

- France

- Germany

- Hungary

- Iceland

- Italy

- Malta

- Norway

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- Spain

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- Australia

- Africa

- North America

- USA

- South America