![]()

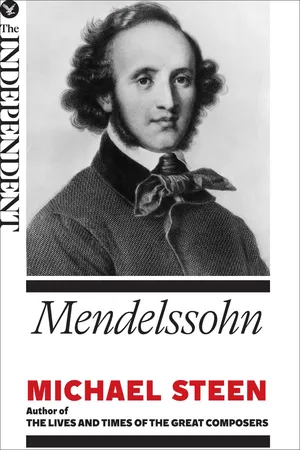

MENDELSSOHN

IT IS NO wonder that Berlioz and Mendelssohn never saw eye to eye. Their different personalities and styles are well illustrated in Mendelssohn’s uncharacteristic outburst to his mother: ‘Berlioz’s instrumentation is so disgustingly filthy … that one needs a wash after merely handling one of his scores.’1 Compared to Berlioz, Mendelssohn was sanitised to perfection, almost excessively refined and restrained, almost classical in his clarity and his structures. Thus, Sibelius could claim that ‘after Bach, Mendelssohn was the greatest master of fugue’.2 In Mendelssohn’s music, as in his short life, there is little of that excessive enthusiasm or exaggeration displayed by Berlioz.

On the other hand, we are apt to associate Mendelssohn with religiosity, sentimentality and other ‘unhealthy’ Victorian values. The Victorians loved his oratorios, his melodious sacred music such as ‘O for the Wings of a Dove’, his Songs Without Words. They appropriated him, even to the extent that he might almost have been thought to be an English composer.

Felix Mendelssohn was born on 3 February 1809, just over five years after Berlioz. Whereas Berlioz’ background was insecure and petty bourgeois, Mendelssohn’s was more assured and cosmopolitan. His teacher introduced him to Goethe, whom he visited on several occasions. At the age of twenty, he conducted the revival of Bach’s St Matthew Passion. Much of his life was spent relentlessly travelling: he went ten times to England. He directed the music at Düsseldorf and at Leipzig. We shall hear of his marriage, his visits to Queen Victoria and his death, less than six months after his sister Fanny died.

THE MENDELSSOHNS

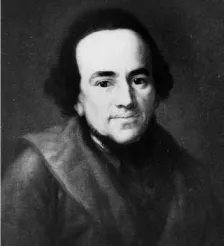

Moses Mendelssohn, Felix’s grandfather, was the son of an impoverished scribe from Dessau, some 40 miles north of Leipzig. Moses became a very distinguished philosopher. Even so, his name has been eclipsed by others, partly perhaps because he was a contemporary of the genius Immanuel Kant,* partly because he was Jewish. It has been said that the modern history of Jewry in its ‘political and intellectual emancipation’ begins with Moses Mendelssohn.3

Moses Mendelssohn

Moses settled in Berlin when his teacher was appointed chief rabbi there. He became the tutor to the children of a rich silk merchant, then an accountant in the merchant’s office, and then a partner in his firm.4 In 1767, Phaedon, his treatise on the immortality of the soul, was published; it was translated into more than 30 different languages; and it was read by Mozart.5

Moses Mendelssohn worked tirelessly to bridge the gap between trad-itional Jewish and the new secular learning.6 Before the 1781 Edict of Tolerance of Emperor Joseph II, Jews had been outsiders; now, at least north of the Alps, there was more scope for them to become integrated. Moses encouraged this. Many ‘assimilated’, while retaining their religion. Others, including several members of Moses’ own family, went much further: they left the Jewish faith so as to gain full acceptance in European society.*

Moses’ son Abraham married Leah Salomon, who came from a family of prominent and rich Berlin Jews who inherited the right of abode and the right to mint money.** At the time Felix was born, Abraham and his brother Joseph were building their own fortune in their bank, Gebrüder Mendelssohn & Co in Hamburg. One supposes that they lent into businesses such as the thriving Hamburg shipping and calico printing concerns:† 9 at the turn of the century, there were 57 calico printing firms in Hamburg, five of which were under Jewish management; some were large, the biggest had 500 employees.

FLIGHT FROM HAMBURG

Until the French garrison took over in 1806, Hamburg’s Jews were tightly regulated as to residence and occupation. In many Jewish communities, the arrival of the French was greatly welcomed because, as elsewhere, the French introduced their laws and procedures, and the Jews were emancipated. Hamburg became a département of France, called the ‘Mouths of the Elbe’. But, for Abraham’s family, the occupation must have been a mixed blessing. The Napoleonic blockade, which was aimed at cutting off Britain’s trade with Continental Europe, devastated Hamburg’s business. However, there were profitable opportunities to be had, and blockade busting and racketeering were rampant and lucrative.

There would have been considerable uncertainty when the French were briefly kicked out by the Russians during 1813. But, by then, Abraham had fled to Berlin with his family, which included Felix and his sisters Fanny and Rebecka. Leaving Hamburg was a pity for a small boy: the city was a centre for the confectionery trade, which used sugar shipped in from the West Indies and Latin America.10 More significantly, however, the Mendelssohns avoided the appallingly harsh defence of Hamburg under Marshal Davoût, during the five winter months starting in December 1813. And they avoided its anti-Semitic conflagrations six years later, after the French had gone and the clock was turned back.11

BERLIN

At the start of the century, Berlin was provincial, small and stuffy: there were only two postal deliveries a week, and it took nine days’ travel along roads infested with highwaymen to reach it from Frankfurt. Gaslight was only very slowly being installed; at ten o’clock at night, the city was deserted. There were fields inside and outside the walls, but the land inside was being bought up for development. In the summer, the dust and smells became intolerable, as did the dirty grass and thick mud in winter. Filth was partly responsible for a cholera outbreak in 1831 which killed many, including the leading philosopher Hegel.12

Berlin was about to revive. Appalled by Prussian defeats in the Napoleonic Wars, the Berliners decided to sort themselves out. The armed forces were reformed by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The educational system was overhauled by Wilhelm von Humboldt, a diplomat, man of letters and linguist, and brother of the world famous scientist and traveller, Alexander von Humboldt.*Wilhelm von Humboldt wanted to replace the French influence that prevailed: so he revised the curriculum for the élite high schools (the Gymnasiums)14 and created the new University of Berlin which was to become the cultural centre for the future Germany. By 1870, virtually every child went to school for eight years and came from a literate family. This created a formidably strong society: by comparison, at the time, almost 70 per cent of the population of Italy over six years of age was illiterate.15

The position of the Jews had been improved by legislation in 1812. There was now considerable pressure for them to ‘assimilate’: those who did not were unable to obtain a position in the state. Leah’s brother converted to Christianity and took the name Bartholdy; and, when Felix was seven, the children were baptised as Lutherans, with the double-barrelled name Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Abraham admitted that Christianity was ‘the creed of most civilised people and contains nothing that can lead you away from what is good, and much that guides you to love – obedience, tolerance and resignation – even if it offers nothing but the example of its Founder, understood by so few and followed by still fewer’.16 Abraham’s personal position, as the son of such a distinguished Jew, was almost impossible, and stressful. He preferred Felix to drop the name of Mendelssohn completely, and reprimanded him for using it during his first trip to England. ‘There should not be a Christian Mendelssohn,’ he said, ‘for my father himself did not want to be a Christian.’17 He and Leah did not convert to Christianity until some years after the children were baptised.

The Mendelssohns had considerable stature in the city. In Moses’ time, many visitors, whether Jew or Gentile, sought to attend a kind of salon which he held in the afternoons. Then, during the Napoleonic Wars, Abraham financed two battalions; this earned him appointment to the city council. Bartholdy was on the staff of the reforming cabinet minister Karl August Hardenberg and accompanied him to the Congress of Vienna; later, he became Prussian commercial attaché in Tuscany.

A PRETTY, PAMPERED BOY

Felix and Fanny, who was three years older, were infant prodigies. By the age of nine, he had played the piano in a private chamber concert. By then, Fanny was playing Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier by heart. Aged eleven, Felix wrote an epic poem in three cantos. As a teenager, he was a more advanced composer than both Mozart and Beethoven at the same age. By seventeen, he had produced the Octet and the overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Rebecka and the younger son Paul, born by the time the family was in Berlin, were less musically exceptional. Paul became a financier.18

Felix was a beautiful boy, with a slight lisp. Weber described ‘his auburn hair clustering in ringlets round his shoulders, the look of his brilliant clear eyes, the smile of innocence and candour on his lips’.19 Thackeray, the author of Vanity Fair, said: ‘His is the most beautiful face I ever saw; I imagine our Saviour’s to have been like it.’20 As he grew up, Felix was athletic; he rode, danced and swam extremely well. Not surprisingly, he became almost obnoxiously self-assured and this manifested itself in him being prim, intolerant and dogmatic. He was highly strung, irritable and moody. Many years later, on his parents’ silver wedding, he planned an operetta in which his friend Eduard Devrient, an actor and a baritone with the Berlin Royal Opera company, was to sing. When Devrient found that he could not participate, because of a competing royal engagement, Mendelssohn became hysterical, and only recovered after going to bed for twelve hours.21

The focus in the Mendelssohn household was the salon. As free speech was curtailed in this period, music, rather than conversation, was the essence of the entertainment. Among the most brilliant were the salons of Leah Mendelssohn and Amalia Beer, wife of the banker Herz Beer, and mother of Meyerbeer. These provided a welcome oasis in a city which Alexander von Humboldt thought displayed ‘bigotry without religion, aestheticism without culture, and philosophy without common sense’.22

It was in this affluent, happy, cultured, yet unostentatious environment that the Mendelssohns lived. They were hard-working. Leah would ask: ‘Felix, are you doing nothing?’ Only on Sundays were the children allowed to get up after 5 am. The family was hierarchical.23 Mendelssohn even consulted his father in his later years on matters of extraordinary detail, such as whether he should buy a horse.24

In 1816, following the Restoration, the Mendelssohns went on a trip to Paris. Abraham did some banking business related to the reparations payable by France for the war. They also saw Aunt Jette, who was a governess there.* Fanny and Felix were given lessons by Madame Bigot, ‘a gifted and stimulating teacher’.25

When he was ten, Felix’s general education was given to a teacher who subsequently became professor of philology at Berlin University. For music theory and composition, he was taught by one of Abraham’s friends, Carl Friedrich Zelter, the director of the Berlin Singakadamie. Zelter was founder of the first of the somewhat hearty male voice choral societies (Liedertafel) which spread throughout Germany. He was also a builder, but more importantly he was a particularly close confidant of Goethe. It has been said that Goethe particularly welcomed Zelter’s settings of his poems because there was little chance that the music would compete with the poetry.26

Zelter was steeped in the traditions of J.S. Bach, whose sons Carl Philipp Emanuel and Wilhelm Friedemann had lived in Berlin. Zelter introduced Abraham to Goethe as he thought Abraham might be able to give the poet some useful investment advice. When Felix was twelve, he was taken to stay with Goethe in Weimar. ‘Every morning I receive a kiss from the author of Faust and Werther and two kisses in the afternoon, from father and friend Goethe. Think of that! … In the afternoon I played for Goethe for more than two hours, Bach fugues and improvisations … I play far more here than I do at home, seldom for less than four hours, often for six and sometimes as many as eight hours … [Goethe] sits down beside me and when I’ve finished, I ask for a kiss or else give him one. You cannot imagine how kind and gracious he is.’27

Felix was doted on by Goethe’s daughter-in-law Ottilie and her sister; and he played with Goethe’s two little grandsons, Walther and Wolfgang, aged four and two. Goethe expressed some concern that the boy tended to be bumptious.28 Mendelssohn must have ignored his father’s orders ‘to keep a strict watch over yourself; to sit properly and behave nicely, especially at dinner; to speak distinctly and suitably, and try as much as possible to express yourself to the point’,29 because at one stage he picked up some bellows and attacked a Weimar lady’s coiffure.

In 1822, Abraham took the family, including the tutor and servants, on a long holiday in Switzerland. They visited all the fashionable sights including Voltaire’s house at Ferney, and the area around Interlaken, Grindelwald and Wengen. Felix, who became a very competent painter, sketched the scenery and many of the waterfalls (see colour plate 41). On the way back, they called on Goethe. In August 1823, Abraham went to Silesia on business and took his two sons with him.

Six months later, on his fifteenth birthday, after the first rehearsal with orchestra of Felix’s opera Der Onkel aus Boston (The Two Nephews), Zelter announced: ‘from today, you are no longer an apprentice, but a fully-fledged member of the brotherhood of musicians. I proclaim you independent in the name of Mozart, Haydn and old father Bach.’30 More works followed. But Abraham and Leah were far too worldly-wise simply to assume that a boy with Felix’s outstanding ability had an assured career in music. Abraham consulted Jacob Bartholdy, the successful diplomat, who wr...