![]()

Small

![]()

Yellow

IN THE SUBURBS of London, on the last day of 1993, terraced houses snuggle up close and another baby – a me-baby – is added to the masses already roaming the streets in their Mothercare perambulators. I have a lopsided mouth and am bald for a long time, but eventually hair grows: white-blonde and fine as gossamer. I have full, pink cheeks and threads on my arms where flesh meets flesh. I have a home and a cot and a Mother and a Father called Mummy and Daddy. I am bonny and bouncing and comically well. Everything has a place, and everything is in its place.

Mummy cuddles and kisses and carries me as much as she can, trying to do the Continuum Method. She breastfeeds for years, wanting to be as close to me as possible. Daddy is distant – yellow-white hair shrinking back to where the top of his head pokes out, bare, like an island. A fleeting presence. Daddy doesn’t think much of babies; when he was young he did the routine of cots and bottles and nappies for the first time, with the mewling bundles which became Half Brother and Half Sister and the partner who became The First Wife. By the time I am born they have splintered off and receded back into the mysterious land of The Previous Relationship, but Daddy still sees them often and carries around a ‘been there, done that’ attitude to small children. But Mummy has not been there or done that. For Mummy, I am the first and the most treasured. Daddy finds this treasuring irritating. As a tired, temperamental infant I look through the bars of my cot-prison and wail with the need to be comforted; cuddled; loved. There is a hunger inside which I don’t have the words to articulate. I am shrill and needy and want Mummy – all of her, all the time – but Daddy wants her for himself. Behind the cot-prison bars, I bawl. After minutes which gape into hours, I am exhausted by the flow of hot, fat tears. My eyes grow heavy and I am nearly asleep when Mummy lifts me into warm arms. Mummy needs me like I need Mummy. Mummy needs to be needed.

I grow and thrive from Baby to Toddler: stubby legs and a round stomach and a halo of thin-thin hair. I talk early and a lot. When I am only two I say things like: ‘Well, that is a good compromise.’ I make everyone laugh and Mummy is proud, but she is also worried. I am bright and able but also brittle and anxious. I don’t sleep. I cling. I cannot cope with the unexpected, or with things going wrong, or with Transitions. When Mummy drops me at playgroup the corners of my mouth jerk downwards and my eyes twinkle with tears – ‘No, don’t WANT to stay!’ – but when she picks me up I am cranky and cold, turning my yellow-dungareed back on her and clinging to the teacher’s hand – ‘No, don’t WANT to go!’ Mummy says I live in a little world where the weather is constantly changing: beatific sun or devastating rain, rarely much in-between.

When I am three and flexing my knees for the leap from Toddler to Girl, another baby happens. Sister. I am pleased to have a sister but also worried because I like having Mummy all to myself. I kiss and cuddle Sister, but I bang my doll’s head on the table and shout at it. Mummy talks on the telephone in big, worried words like ‘Displacement’ and ‘Pent-Up Aggression’ when she thinks I am engrossed in the neon world of the Teletubbies, and says to her Phone-Friend: ‘Can I borrow your copy of Siblings Without Rivalry?’

When I start school I decide I must most definitely be a Girl now. I wear a grey skirt and a white shirt and a soft blue cardigan and feel Very Grown-Up. In Reception, I try to say the most and know the most and answer most of the questions Teacher asks us when we sit on the carpet, frog-legged, close enough to one another for the nits to leap from head to itchy head. I get given a special little red book for Literacy with all lined pages because I write more than can be fitted into the normal Reception books, which have lots of blank space for silly old pictures. Teacher says it is unusual to be able to write so much when you are so small. I glow inside. Usual sounds so grey and wet. I am unusual. Un-usual. It is sparkly and exciting.

In Years One and Two and Three and Four I get bigger and rounder and better. My insides sometimes scrunch and cower – when I can’t remember my times tables; when tetchy teachers deliver whole-class scoldings which seem conspicuously, pointedly addressed towards me; when the playground feels like a cold, lonely concrete cage full of noisy, shouty children who are not my friends – but I plaster over their squirming with layers of crumbly confidence. I can’t afford to be as small and scared as I feel; I have to be Perfect. If I’m not Perfect things are topsy-turvy and back-to-front and itchy-scratchy and wrong. If I’m not Perfect, no one will like me. If I’m not Perfect, nothing is in its place. I count the ticks in my exercise books, covering up crosses with chubby fingers, pretending they aren’t there. Hating the way they tarnish me. I speak in a big, loud voice, so in Class Assembly I usually have the biggest part: one time I am a cat sitting on top of a roof and another time I am the narrator (there are lots and lots of words to learn that time). I am Mature and Responsible, so I am often the one who gets asked to do errands for the teacher. I work hard at perfecting my Mature-and-Responsible skills, because I want everyone to be proud of me.

Being Perfect is especially important now, as by this time Sister is getting bigger every day, starting in Reception and nipping at my heels. Sister’s growing up makes me angry. I can’t say whether the anger is directed at Sister, for trying to steal the limelight, or at myself, for not being exceptional enough to hold onto it. I suspect the latter – I am quickly learning that most problems can be traced back to faults within myself. ‘Please, please don’t let Sister be the star’, I think as I curl up, safe in the privacy of night-time. ‘Please, please don’t let her be better than me.’

At home, Mummy is kind and warm and Sister and I want to be with her all the time. She is all the colours of an autumn leaf, I think – short brown hair and kind, pretty brown eyes. After years of sunlight, her skin has been dyed mottled brown too: soft, weather-worn skin which hangs looser and looser as the years go by (I like to pinch it softly, rolling it between the pads of finger and thumb, puzzled by the way my own flesh springs stubbornly back into shape after the same manipulations). I am also fascinated by the moles which speckle Mummy’s arms – the same moles which colonise my shoulder blades, soft and brown and underdeveloped on my small form. Mummy’s moles have sprouted with age, just as lines have gently furrowed themselves into her face over the years, deepening each time she smiles wide enough to reveal the tiny gap between her front teeth. Sometimes I watch, transfixed, as Mummy bites into a piece of toast and butter comes through the tooth-gap.

While Mummy has a soft, ex-baby-house stomach on her slender frame, Daddy is normal-sized all over, but to me he seems enormous – tall and towering. Like Mummy, his face is patterned with lines, criss-crossed like roads on a map, from years of smiling and laughing but mostly of frowning. Sometimes, after a long time of frowning, Daddy takes the big, square glasses off his nose and rubs his eyes with his knuckles as if an unnamed Something is making him very, very tired. I see him do this a lot at home, and I think perhaps I make him very, very tired.

Daddy is In Television, which sounds like ON Television but is not as exciting. Daddy is a di-rec-tor, bossing everyone ON television about from behind the cameras. The stacks of scrap paper which bear my crayon-crafted works of art are leftover scripts, and the concept of the world existing through a camera lens – as a series of wide shots and closeups – is one woven into the fabric of my DNA. I am proud of the scrap-script mountains in my house, and proud of having a Daddy In Television. I boast about it to everyone at school, but really it is not anything to boast about because it seems like there is just not enough Television to go round these days and Daddy is often out of a job. And this makes him cold and sad and grey.

Mummy is fun and Daddy is strict. Mummy lets me and Sister stay up late and sometimes even lets us wrap up warm and takes us out for walks when it’s pitch-black-night-time outside and this makes me feel special and grown-up and important. Daddy tells me off a lot – for Talking With My Mouth Full and Dropping My Coat On The Floor and Not Making My Bed – and this makes me feel horrid and messy and lazy. I sometimes hear Mummy and Daddy fight about how Mummy is fun and Daddy is strict. There are more big, worried words then, like Unified Front and Lack of Discipline. I do not understand them, but they sound cold and dangerous. But we are a good little family of performers, following the script set out for us to the letter.

Scene One: The Dinner Table

[Shot of family – Mummy, Daddy, Nancy, Sister – sitting eating dinner together]

Nancy (animated)

Today at school when it was lunchtime at school and –

Daddy [flat]

Don’t talk with your mouth full.

Mummy

What happened at lunchtime, sweetheart?

Nancy

It was at school and I was on the steps and then I was going to come down but –

[Sister throws handful of mashed banana from high chair onto floor]

Mummy

Oh dear, what happened there, poppet?

[Daddy sighs. Sister gurgles, smiling. Mummy strokes her hair. Nancy pulls Mummy’s skirt]

Nancy (almost shouting)

Mummy, it was at school and I went down the steps but then I got a bit of my shoe – like this bit here – this bit of my shoe – stuck on the step and it was lunchtime and –

[Daddy sighs again. He leaves the table. Mummy wipes Sister’s face, making ‘listening’ noises in Nancy’s direction]

Mummy

Really, darling? Is that right? What a funny thing to have happened!

[Nancy slumps down in chair, chewing her cardigan sleeve]

Nancy’s Inside Voice (voiceover)

No. That’s not right. I hadn’t even finished. Nobody is listening.

Nancy (very quietly)

Yes. So funny.

[CUT]

As well as Mummy and Daddy and now Sister (whom I am still not all that sure about), Granny and Grandpa occupy a cosy corner of my life. These are Mummy’s Mother and Father – Daddy’s family are all either dead or living far away in mysterious places like The Other Side of the Motorway. Mummy’s family all live just around the corner so they are the ones I see often and spend most time with, and this seems to make Daddy cross. I don’t really understand why.

Granny and Grandpa have a big, long garden with a bay tree in the middle, and in summertime there is a sprinkler and tiny bare bodies run in-out-in-out, dripping onto the sitting room carpet and knowing that the drips will not be met with scrunched eyebrows or cross voices. One weekend, Mummy says, ‘Do you want to take any toys with you when we go to Granny and Grandpa’s house?’ and I say: ‘Don’t be silly, Mummy. Granny has her own toys.’ And she does – baskets and baskets of toys, and offcuts of fabric for wonky cross-stitch and a shed for carpentry and a table set up for painting in the attic and blackberries to be picked from the garden hedges. Granny has everything and knows everything and does everything she can to keep me and Sister occupied, and though, like Daddy, she wears glasses – enormous glasses which hang on a chain round her neck and magnify her eyes like an owl’s – she never has to take them off to rub tired eyes, even though she is old. Granny never seems tired at all – she is always ready to go out on trips or play games or just listen to the things I have to tell her, while Grandpa sits in Grandpa’s Chair and Sister falls asleep on his knee.

I grow up falling asleep in dressing rooms, swinging on the handles of stage doors and assembling make-shift step ladders out of yet more scripts, because Granny and Grandpa are In Theatre, and in this case really IN theatre, not just behind the scenes making things happen (which is what Mummy does – or what she did before mine and Sister’s advent). I am proud to be part of a Theatrical Family, and pretend to enjoy the productions of The Cherry Orchard and Separate Tables in front of which I doze at five, six and seven years old. I think it is Very Special Indeed to be part of such a mysterious, sparkly world – to see people on a stage and then, minutes later, see them again, the same and also different, back in Real Life – but I also find the thought of being up on a stage with millions of people staring at you very scary. They might not like you, might laugh at you for being too small or too fat or too ugly. You might be on the stage with lots of other people, and the other people might be better than you, and the lights might get in your eyes, and you might make a mistake and not be Perfect. And what then? But performance surrounds me, and I feel the weight of expectation like a leaden scarf around my shoulders.

Scene Two: ‘When you grow up…’

[Grown-Ups cluster around a seven-year-old Nancy. They are loud and exclamatory; she is tense and quiet]

Grown-Up One

So, would you like to go into The Business when you’re older?

Nancy

Oh yes, of course…

Grown-Up Two

And you’re planning on following in the family footsteps, I assume?

Nancy

Absolutely, yes…

Grown-Up Three

And you’ll be the next actress in the family, I hear?

Nancy

Definitely…

Grown-Up Four

It’s in your blood, isn’t it? I imagine all you want to do is perform?

Nancy

Yes, yes, definitely, I just want to act…

Nancy’s Inside Voice (voiceover)

Yes, yes, please like me, I just want to be what you all want me to be…

[CUT]

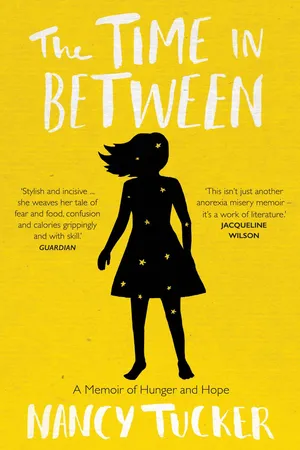

There are sad bits interwoven with the sparkle of my world during The Young Time. Mummy and Daddy get cross with each other and retreat into themselves, flexing small, tight muscles of resentment. People die – indeterminate uncle/aunt/family friend characters whose passing engenders in me not grief, but an uneasy sense of foreboding, scrabbling like an unruly ferret at the bottom of my stomach. (‘Please don’t let Mummy die,’ I whisper at night, eyes tight shut, fingers and toes crossed, willing the prayer to wrap a shield around her, to preserve her as the solid centre of my Little Girl World. ‘Please, please don’t let Mummy die.’) I sometimes feel sad and can’t explain why; Mummy sometimes cries and I don’t understand why; I feel a deep-seated fear – of Daddy; of The Future; of not being Good Enough – and wish I knew why. But the overwhelming colour of my early world is yellow: bright, warm, welcoming yellow. Playing on the streets, falling down, blood trickling down into frilly white socks and strong, safe arms lifting up, up, up. Twenty pence pieces clutched in hot hands, then exchanged for technicolour sweets in cardboard tubes which stain fingers like paint, their purchase echoed by the ting-a-ling of the bell on the door of the corner shop. Days spilling into nights; months spilling into years; babies spilling into boys and girls.

Yes; The Young Time is yellow.

![]()

Pink

Christmas – 1998 – Five Years Old

Excitement fizzles in my tummy from the first of December, pop-pop-pop, effervescing like bath salts. Christmas is everywhere – in the smell of the cold days, the lethargy of the end-of-term lessons at school, the thrill of popping open a new cardboard window every day to reveal a picture of a shepherd, or a star, or a bulging stocking. (In an uncharacteristically wholesome way, Mum disapproves of chocolate advent calendars. Sister and I grudgingly make do with pictures, gazing wistfully at friends’ Cadbury alternatives when we go round for tea.) There is a double calendar-window on Christmas Eve, opening like the big doors out onto the garden at Granny and Grandpa’s house, and that night I cry and cry and panic because my brain and my tummy are tick-tick-ticking too fast to let me sleep but I know that if I don’t sleep I’ll be tired on The Big Day and then Everything Will Be Ruined.

Christmas is full of fizzy feelings. Frenzied excitement so heady it’s like champagne bubbles frothing in my nose. Real champagne bubbles which do froth in my nose and make me feel gloriously, glamorously Grown-Up. Crushing despair as I clamber into the car to go home from Granny and Grandpa’s house and realise that it’s all over for another year.

I wear a pink, flouncy satin dress. A party dress. The fabric is soft against my skin and makes a snick-snick-snick noise when I move. I am dizzy with the pride of Dressing Up. I get a fairy costume from my cousins this Christmas, with a soft top and long, gauzy skirt, dotted with silver stars. And wings. AND a wand. I go out of the room and Biggest Cousin pulls it over my head, over my gr...