- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

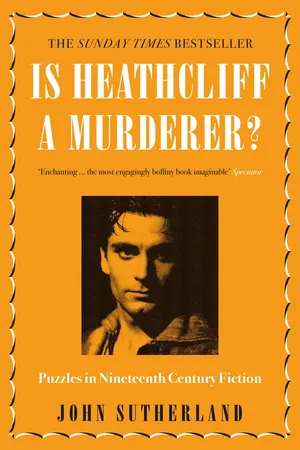

THE SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLER IN A BRAND NEW EDITION'Enchanting...the most engagingly boffiny book imaginable.' Spectator Does Becky kill Jos at the end of Vanity Fair? Why does no one notice that Hetty is pregnant in Adam Bede? How, exactly, does Victor Frankenstein make his monster?

Readers of Victorian fiction often find themselves tripping up on seeming anomalies, enigmas and mysteries in their favourite novels.

In Is Heathcliff a Murderer? John Sutherland investigates 34 conundrums of nineteenth-century fiction, paying homage to the most rewarding of critical activities: close reading and the pleasures of good-natured pedantry

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Is Heathcliff a Murderer? by Jon Sutherland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Two-timing novelists

Early nineteenth-century novelists had an engagingly cavalier attitude to finer points of chronology. One of Dickens’s footnotes in Chapter 2 of the 1847 reissue of The Pickwick Papers is typical of the freedoms they allowed themselves in such matters. Mr Jingle, in response to Pickwick’s observation that ‘My friend Mr Snodgrass has a strong poetic turn’, replies: ‘So have I … Epic poem – ten thousand lines – revolution of July – composed it on the spot.’ When asked, he assures the amazed Pickwick that he was, indeed, there at the event and saw the blood flowing in the Parisian gutters. Dickens adds the footnote to this exchange: ‘A remarkable instance of the prophetic force of Mr Jingle’s imagination; this dialogue occurring in the year 1827, and the Revolution in 1830.’1

Scott is equally good-natured about his chronological solecisms in Rob Roy. When Andrew Fairservice urges the hero, Frank Osbaldistone, to accompany him to ‘St Enoch’s Kirk, where he said “a soul searching divine was to haud forth”’, the novelist added the bland footnote (evidently as the result of a friend’s observation): ‘This I believe to be an anachronism, as St Enoch’s Church was not built at the date of the story [1715].’2 No more than Dickens, apparently, did Scott think of changing his anomalous text.

Scrupulosity about narrative chronology tightened up during the Victorian period, reaching a fetishistic pitch with the intricate sensation novels of Wilkie Collins. The older school of novelists were not, however, sure that they altogether liked the new orderliness about such things. Trollope voiced a typically bluff complaint in his comments on Collins in An Autobiography:

Of Wilkie Collins it is impossible for a true critic not to speak with admiration, because he has excelled all his contemporaries in a certain most difficult branch of his art; but as it is a branch which I have not myself at all cultivated, it is not unnatural that his work should be very much lost upon me individually. When I sit down to write a novel I do not at all know, and I do not very much care, how it is to end. Wilkie Collins seems so to construct his that he not only, before writing, plans everything on, down to the minutest detail, from the beginning to the end; but then plots it all back again, to see that there is no piece of necessary dovetailing which does not dove-tail with absolute accuracy. The construction is most minute and most wonderful. But I can never lose the taste of the construction. The author seems always to be warning me to remember that something happened at exactly halfpast two o’clock on Tuesday morning … (Chapter 13)

Trollope’s underlying gripe would seem to be that by clock and calendar-watching Collins had deprived novelists and readers of valuable traditional liberties. In support of Trollope’s preference for the old easygoing ways, we may examine chronological cruxes in three Victorian novels of the 1850s and 1860s, Thackeray’s Pendennis, Mrs Gaskell’s A Dark Night’s Work, and Trollope’s own Rachel Ray. Closely examined, they suggest that what looks like slovenliness about chronology in Victorian fiction can plausibly be seen as an artistic device which these three novelists, at least, used to powerful effect.

Pendennis was Thackeray’s second major novel and it was, even by Victorian standards, an immensely long work (24 32-page monthly numbers, compared to the twenty that made up Vanity Fair). It took some 26 months in the publishing (November 1848–December 1850), interrupted as it was by the novelist’s life-threatening illness which incapacitated him between September 1849 and January 1850. Pendennis is also long in the tracts of time its narrative covers. The central story extends over some 40 years as the hero, Arthur Pendennis (‘Pen’), grows from boyhood to mature manhood. In passing, Pen’s story offers a panorama of the changing Regency, Georgian, Williamite, and Victorian ages.

Pendennis is one of the first and greatest mid-Victorian Bildungsromanen. The central character, as Thackeray candidly admitted, is based closely on himself. As part of this identification, Thackeray gave Arthur Pendennis the same birth-date as himself – 1811. This is indicated by a number of unequivocal historical markers early in the text. Pen is sixteen just before the Duke of York dies in 1827. We are told that Pen (still sixteen) and his mother recite to each other from Keble’s The Christian Year (1827), ‘a book which appeared about that time’. Pen’s early years at Grey Friars school and his parents’ Devonshire house, Fairoaks, fit exactly with Thackeray’s sojourns at Charterhouse school and his parents’ Devonshire house, Larkbeare. Both young men go up to university (‘Oxbridge’, Cambridge) in 1829. Both retire from the university, in rusticated disgrace, in 1830. Thackeray clinches this historical setting by any number of references to fashions, slang, and student mores of the late 1820s and 1830s, as well as by a string of allusions to the imminent and historically overarching Reform Bill.

Switch from these early pages to the last numbers of the novel, where we are specifically told on a number of occasions that Pen is now 26. This is supported by any number of historical allusions fixing the front-of-stage date as the mid-to-late 1830s.3 Pendennis is given its essentially nostalgic feel by historical and cultural events dredged up from the past, between ten and twenty years before the period of writing. And yet, there are a perplexing string of references which locate the action in the late 1840s, indeed, at the precise moment Thackeray was writing. In the highpoint scene of Derby Day in Number 19 of the serial narrative we glimpse among the crowd at the racecourse the prime minister, Lord John Russell, who took up office in 1846, and Richard Cobden MP. Cobden did not enter Parliament until 1847. And, by cross-reference to Richard Doyle’s well-known Derby Day panorama in Punch, 26 May 1849 (a work which inspired Frith’s famous Derby Day painting), we can see that Thackeray is clearly describing the Derby of the year in which he wrote, which actually took place a couple of months before the number was published.

Thackeray, as has been said, is insistent in this final phase of his narrative that Pen is just 26 years old, which gives a historical setting of 1837. But, at the same time, Pen is given speeches like the following (one of his more provokingly ‘cynical’ effusions to Warrington), in Number 20:

‘The truth, friend!’ Arthur said imperturbably; ‘where is the truth? Show it me. That is the question between us. I see it on both sides. I see it in the Conservative side of the House, and amongst the Radicals, and even on the ministerial benches. I see it in this man who worships by Act of Parliament, and is rewarded with a silk apron and five thousand a year; in that man, who, driven fatally by the remorseless logic of his creed, gives up everything, friends, fame, dearest ties, closest vanities, the respect of an army of churchmen, the recognized position of a leader, and passes over, truthimpelled, to the enemy, in whose ranks he is ready to serve henceforth as a nameless private soldier: – I see the truth in that man, as I do in his brother, whose logic drives him to quite a different conclusion, and who, after having passed a life in vain endeavours to reconcile an irreconcilable book, flings it at last down in despair, and declares, with tearful eyes, and hands up to heaven, his revolt and recantation. If the truth is with all these, why should I take side with any one of them?’ (Chapter 42)

No well-informed Victorian reading this in 1850 could fail to pick up the topical references. In his remark on the ‘ministerial benches’ Pen alludes to the great Conservative U-turn over the Corn Laws in 1846 (in which the aforementioned Cobden and Russell were leading players). His subsequent references are transparently to John Henry Newman (1801–90) and his brother Francis William Newman (1805–97). John went over to the Catholic Church in 1845. As Gordon Ray’s biography records, Thackeray attended his course of lectures on Anglican difficulties at the Oratory, King William Street, in summer 1850 (this number was published in September). Francis, professor of Latin at University College London, 1846–69, published his reasons for being unable to accept traditional Christian arguments in the autobiographical Phases of Faith (1850). According to Gordon Ray, Thackeray was much moved by the book. Clearly Pen’s comments to Warrington only make sense if we date them as being uttered in mid-1850, at the same period that this monthly number was being written. And we have to assume that Thackeray was making his hero the vehicle for what he (Thackeray) was thinking on the great current question of Papal Aggression.

These examples of ‘two-timing’ in Pendennis are systematic features of the novel’s highly artful structure. Thackeray has devised a technique that was to be later explored and codified into a modernist style by the Cubists. Not to be fanciful, the author of Pendennis anticipates Picasso’s multi-perspectival effect whereby, for example, more than one plane of a woman’s face could be combined in a single image. Pen and his mentor Warrington in the above scene are at the same time young men of the 1830s and bewhiskered, tobacco-reeking, ‘muscular’ hearties of the early 1850s, verging on middle-age. They inhabit the present and the past simultaneously, offering two planes of their lives to the reader.

Mrs Gaskell first published her novella A Dark Night’s Work as a stopgap serial in Dickens’s journal, All the Year Round. (Charles Reade needed more time to prepare for his massively documented sensation novel, Hard Cash.)4 Mrs Gaskell’s tale first appeared as instalments between 24 January and 21 March 1863 in the journal and was reissued as a one-volume book later in the year. It would seem, however, that the work had an earlier origin. As the Oxford World’s Classics editor, Suzanne Lewis, notes, ‘although published in 1863, A Dark Night’s Work was, according to a letter from Elizabeth Gaskell to George Smith, begun in about 1858’.5 Lewis goes on to connect this double date (composition beginning in 1858, publication occurring in 1863) with an important dating reference in the story’s first sentence: ‘In the county town of a certain shire there lived (about forty years ago) one Mr Wilkins, a conveyancing attorney of considerable standing’ (Chapter 1). The editor notes that by simple subtraction we may assume ‘that the early events of the tale take place sometime between 1815 and 1820’.

The earliest events told in the tale are Mr Wilkins’s courtship of his wife which, thanks to a reference to the state visit of the allied sovereigns (Ch. 1), we can locate as taking place in the months directly following June 1814, when the Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia were entertained in London. Mr Wilkins is subsequently widowed very young and left with his daughter, Ellinor, as his only consolation (a younger daughter dies a baby, soon after her mother). At fourteen, as we are told, Ellinor makes a friend of Ralph Corbet, who is studying with a clergyman-tutor nearby. And, four years or so later, the two young people are deeply in love. Meanwhile, Mr Wilkins has conceived a huge dislike for his obnoxiously efficient chief clerk, Mr Dunster, and his conveyancing business is going to the dogs.

Already some of the time-markers in A Dark Night’s Work are beginning to go astray. As Suzanne Lewis notes, Ellinor, at some point shortly before 1829, is described visiting Salisbury Cathedral, where she earnestly discusses ‘Ruskin’s works’ with the resident clergyman, Mr Livingstone (Ch. 6). Nothing of Ruskin’s would have been available until decades later, and certainly not The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and its extended discussions of the beauty of Salisbury Cathedral, which is what Mr Livingstone and Miss Wilkins are evidently supposed to be discussing.

Events crowd on quickly, driven by Mrs Gaskell’s penchant for melodrama. In one of his drunken rages, Mr Wilkins strikes out and kills Dunster. In their ‘dark night’s work’, Ellinor, the loyal servant Dixon, and Mr Wilkins bury the clerk’s body, allowing it to be thought that he has stolen money from the firm and decamped to America. Under the strain of complicity, Ellinor falls ill; the engagement with Ralph Corbet is broken off; Mr Wilkins declines into chronic drunkenness and dies soon after, shattered by remorse and guilt. Ellinor is left virtually penniless, and goes to live a retired and self-punishingly religious life at East Chester. The narrative specifically d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction and Acknowledgements

- Where does Sir Thomas’s wealth come from?

- How much English blood (if any) does Waverley spill?

- Apple-blossom in June?

- Effie Deans’s phantom pregnancy

- How does Victor make his monsters?

- Is Oliver dreaming?

- Mysteries of the Dickensian year

- Is Heathcliff a murderer?

- Rochester’s celestial telegram

- Does Becky kill Jos?

- Who is Helen Graham?

- What kind of murderer is John Barton?

- On a gross anachronism

- What is Jo sweeping?

- Villette’s double ending

- What is Hetty waiting for?

- The missing fortnight

- Two-timing novelists

- The phantom pregnancy of Mary Flood Jones

- Is Will Ladislaw legitimate?

- Is Melmotte Jewish?

- Where is Tenway Junction?

- Was he Popenjoy?

- R.H. Hutton’s spoiling hand

- What does Edward Hyde look like?

- Who is Alexander’s father?

- Why does this novel disturb us?

- Is Alec a rapist?

- Mysteries of the Speckled Band

- What does Arabella Donn throw?

- What is Duncan Jopp’s crime?

- Why is Griffin cold?

- Why does the Count come to England?

- How old is Kim?

- About the Author

- Copyright

- Advertisement