- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Imagine That - Technology

About this book

Technology's most intriguing stories are the tales of what might have been, those seemingly insignificant incidents that would have had the largest unforeseen effects.Imagine That…Alexander Fleming cleans up his dishes … and penicillin is washed down the drainSteve Jobs skips the company visit to Xerox PAR C … and computers never crack the commercial marketNikola Tesla receives philanthropic support … and the 20th century is illuminated by space age energy and technology

Engaging, contentious and compulsively readable, each book in this new series takes the reader on a historical flight of fancy, imagining the consequences if history had gone just that little bit differently.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Imagine that …

Alexander Fleming cleans up his dishes … and penicillin is washed down the drain

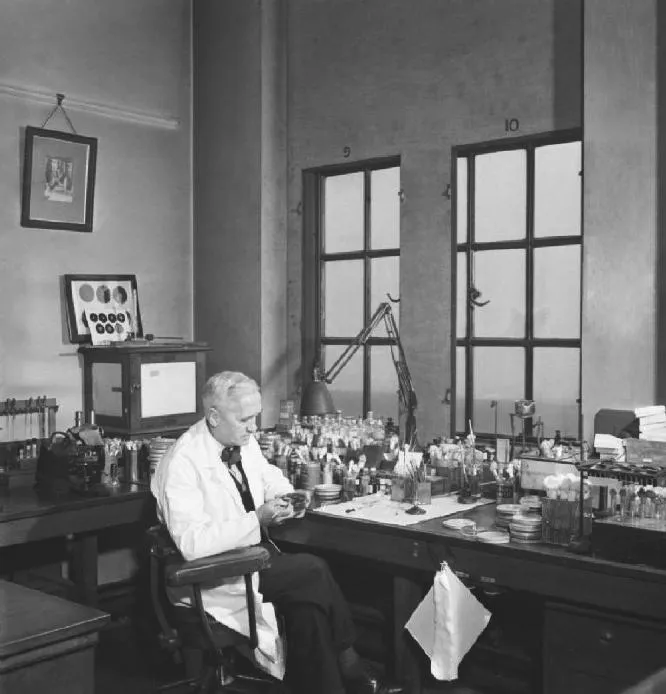

Following a month-long family holiday, Alexander Fleming returned to St Mary’s Hospital on the morning of 3 September 1928. The Scot found his laboratory even more cluttered than usual. He had hastily swept his petri dishes to one side before his trip, to clear room for his lab partner Stuart R. Craddock, and the dishes were now piled high. His first task of the day was to sort them. Unsurprisingly, after stewing in the laboratory for a month, the majority of the cultures growing in the dishes had been swamped by mould. Fleming took a large tray of Lysol disinfectant and began placing the contaminated samples within. Normally this would have been a job for a lab assistant but, eager to get back to work, he undertook the task himself. A pivotal distraction soon arrived in the form of D Merlin Pryce, Fleming’s ex-lab assistant, stopping by to welcome him back from holiday.

Six years earlier Fleming had made a key scientific discovery which had drastically impacted upon his work in medicine. At the time, he was monitoring the condition of a patient who was suffering heavily from a head cold, collecting mucus and applying it to samples of bacteria on a daily basis. After a few days of no reaction, the mucus suddenly began to fight the bacteria on day four, successfully killing off large patches and weakening the rest. This had never been seen before. He soon discovered that he was observing the effects of Lysozyme, a naturally occurring bacteria-fighting agent present in tears and mucus.

Newly aware that it was possible to fight bacteria safely and successfully, Fleming spent the following years attempting to devise a drug that would do exactly that. He had been growing cultures of a bacterium called Staphylococcus aureus (Staph aureus) prior to his holiday, a strain responsible for a number of diseases and infections. Staph aureus was just the latest target in a long line of tests.

As he discussed his ongoing research with Pryce, the pair pored over the mouldy dishes. The Lysol tray was now overflowing with contaminated samples and only a handful of dishes at the bottom were fully disinfected. Fleming pulled one of the unwanted samples from the tray to show to his former colleague. Pryce instantly noticed something highly unusual. Where the spores of mould had formed, no bacteria surrounded them – the same phenomenon that Fleming had observed in the Lysozyme. This could mean only one thing: the key to the cure lay in the mould.

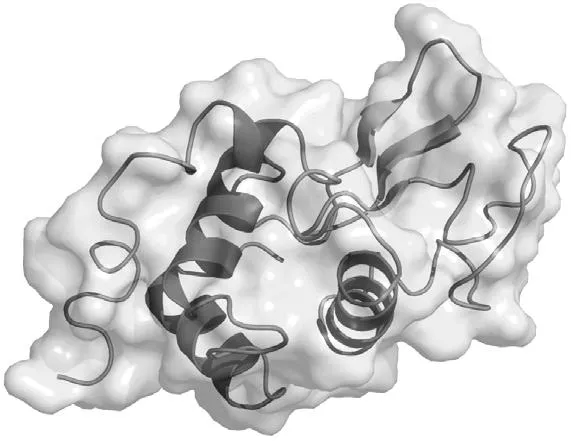

He enlisted the help of his lab assistants and partners and set about studying the mould in greater detail. After growing the mould in a pure form they identified the substance as a derivation of a genus of fungi named Penicillium and so penicillin was born. This provided a much needed update from its previous moniker of ‘Mould Juice’. The team soon found that it could combat far more than just Staphylococcus. More importantly, their studies showed penicillin to be non-toxic. In 1888, a German scientist named E. de Freudenreich had managed to isolate an antibacterial substance named Pyocyanase, but faced one small problem. Pyocyanase was highly toxic to humans. Fleming’s work on both Lysozyme and penicillin had proven that non-toxic antibiotics were a possibility. Work began on creating exactly that.

Fleming and his team lacked the required expertise to do this though, so they handed over the research. It was picked up by a team of pharmacologists based at Oxford University, led by Howard Florey (left) and Ernst Chain. It would take a decade and a horde of tireless biochemists the world over to transform the raw penicillin into the world’s first antibiotic. After a number of years’ worth of successful trials had been carried out on mice, the first ‘positive’ human trial ended in tragedy.

In February of 1941, Reserve Constable Albert Alexander of the County of Oxford Police Department sustained an injury to the inside of his mouth while pruning roses in his garden. He was rushed to hospital having contracted an aggressive infection which caused large abscesses to form both internally and on the surface of his body. With a host of trial data supporting the drug, it was finally time to try penicillin out on a human. The doctors were given the go-ahead and Constable Alexander’s course of treatment began. The early signs were hugely encouraging and, what with the abscesses clearing and his overall condition improving greatly, he looked like he would make a full recovery.

The medical team were still learning about penicillin, however, and, with no prior practical experience, mistakes were always a possibility in the maiden test. The doctors fell short of the required dosage and when supplies ran out they were unable to produce more due to the wartime restrictions placed upon the laboratory. Without penicillin to aid him, Constable Alexander suffered a relapse and eventually died on 15 March 1941. It was a personal tragedy but a medical triumph. The patient’s initial response left the team in no doubt as to the drug’s healing capabilities. Numerous successful trials followed and penicillin began to make its way into the hands of doctors.

Serving in World War I, Fleming had seen first-hand the damning effects of bacteria in warzones, with even the most innocuous looking grazes rendered fatal. It was a harsh reality that had long troubled him and was the driving force behind his successful research. His hopes were realised in 1941, thanks to Howard Florey. With the US entering into the war, Florey managed to persuade American pharmaceutical companies to mass produce the drug. No fewer than 39 laboratories were set up across the United States with the specific intention of synthesising inorganic penicillin for mass production. In 1943 British companies followed suit.

By 1944 there were sufficient supplies of penicillin to cover the Allied armies, providing a much needed boost at a crucial stage of the conflicts. The new antibiotic meant that patients needing surgery could be sustained for longer, keeping infections at bay so that many received life-saving surgery and treatment that would otherwise have been futile. It was the perfect drug for the army, since it did not require refrigeration like many other medicines that had been developed up until then. As a result, large quantities could be stored easily, which was a necessity when caring for entire army camps. Death and amputation rates soon dropped.

The worldwide effort to develop this ‘wonder drug’ meant that there need not be a repeat of the sad case of Constable Alexander: by the end of World War I, penicillin was 20 times more potent than the pre-war trial version. Small scratches were no longer potentially fatal, even in undeveloped nations. Doctors were now able to save children from scarlet fever and stomach infections. It was not just the potency that had increased either. By the 1950s, more than 250,000 patients a month were being prescribed penicillin for their ailments. Never before had pharmacists possessed a drug that was in such ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Chapter 1: Imagine that: Alexander Fleming cleans up his dishes … and penicillin is washed down the drain

- Chapter 2: Imagine that: Nikola Tesla receives philanthropic support … and the 20th century is illuminated by space age energy and technology

- Chapter 3: Imagine that: The transistor falls to a lack of fortuitous findings … and modern technology remains out of mind and reach

- Chapter 4: Imagine that: Steve Jobs skips the company visit to Xerox PARC … and computers never crack the commercial market

- Chapter 5: Imagine that: Mark Zuckerberg abandons his Facebook project after early difficulties … and the internet enters its golden age

- Chapter 6: Imagine that: Percy Shaw runs over a cat … and countless more lives are lost in road accidents

- Chapter 7: Imagine that: X-ray technology goes undiscovered … and the limitations of science remain unknown

- Chapter 8: Imagine that: Wilson Greatbatch can’t afford to invent the pacemaker … and quality of life for heart patients plummets

- Chapter 9: Imagine that: The Newspaper Radio is a huge success upon release … and 24-hour journalism begins in 1939

- Chapter 10: Imagine that: Mobile phones fail to catch on commercially … and we become a more vocal society

- Other books in the series:

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Imagine That - Technology by Michael Sells in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.