1. In the mirror

Stand in front of a mirror, preferably full length, and take a good look at yourself. Not the usual glance – really take in what you see. You may become a little coy at this point. It’s easy to start looking for imperfections, noticing those extra centimetres on the waistline, perhaps. But that’s not the point. I want you to really look at a human being.

In this book you are going to use the human body, your body, to explore the most extreme aspects of science. It’s all there. Everything from the chemistry of indigestion to the Big Bang and the most intractable mysteries of the universe is reflected in that single, compact structure. Your body will be your laboratory and your observatory.

You can look at the whole body, treating it as a single remarkable object. A living creature. But you can also plunge into the detail, exploring the ways your body interacts with the world around it, or how it makes use of the energy in food to get you moving. Zoom in further and you will find somewhere between ten and 100 trillion cells. Each cell is a sophisticated package of life, yet taken alone a single cell is certainly not you. Go further still and you will find complex chemistry abounding – you have a copy of the largest known molecule in most of your body’s cells: the DNA in chromosome 1.

Continue to look in even greater detail and eventually you will reach the atoms that make up all matter. Here traditional numbers become clumsy; a typical adult is made up of around 7,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms. It’s much easier to say 7 × 1027, simply meaning 7 with 27 zeroes after it. That’s more than a billion atoms for every second the universe is thought to have existed.

There’s a whole lot going on inside that apparently simple form that you see standing in front of you in the mirror.

On reflection

In a moment we’ll plunge in to explore the miniature universe that is you, but let’s briefly stay on the outside, looking at your image in the mirror. Here’s a chance to explore a mystery that puzzled people for centuries.

Stand in front of a mirror. Raise your right hand. Which hand does your reflection raise?

As you’d expect from experience, your reflection raises its left hand.

Here’s the puzzle. The mirror swaps everything left and right – something we take for granted. Your left hand becomes your reflection’s right hand. If you close your right eye, your reflection closes its left. If your hair is parted on the left, your reflection’s hair is parted on the right. Yet the top of your head is reflected at the top of the mirror and your feet (if it’s a full-length mirror) are down at the bottom. Why does the mirror switch around left and right, but leave top and bottom the same? Why does it treat the two directions differently?

Here’s a chance to think scientifically. There are three things influencing how the mirror produces your image. The way light travels between you and the mirror, the way that you detect that light (with your eyes) and, finally, the way that your brain interprets the signals it receives. We will explore all of these aspects of your body in more detail later in the book, but one significant point may leap out immediately as you think about the process of seeing your reflection. Your eyes are arranged horizontally. You have a left and a right eye, not top and bottom eyes. Could this be why the switch only happens left and right?

Sadly, no. It’s a pretty good hypothesis, but in this case it’s wrong. That’s not a bad thing; much of our understanding of science comes from discovering why ideas are wrong. Let’s try a little experiment that will help clarify what is really happening.

Experiment – On reflection

Hold up a book (or magazine) in front of you, closed, with the front cover towards you. Look at the book in the mirror. What do you see? Be as precise as possible. List everything that you can say about the reflected book. Does this help explain why the mirror works the way it does?

Do try this yourself first, but here’s what I see:

- The book in the mirror is printed in mirror writing, swapped left to right.

- The reflected book is as far behind the mirror as my book is in front of it.

- The book’s colours are the same in the mirror as they are on my side.

- The front cover of the book in the mirror is the back cover of my book.

Just take a look at that last statement. If I simply consider the book in the mirror to be an ordinary book then, as I look at it, my book’s back cover has become the mirror book’s front cover. Lurking here is the explanation of the mirror’s mystery. It doesn’t swap left and right at all. It swaps back and front.

In effect, what the mirror does is turn an image inside out. The back of my book becomes the front of the book in the mirror. Put the book down and look at your own reflection again. Imagine that your skin is made of rubber and is detachable. Take off that imaginary skin, move it straight through the mirror and, without turning it round, turn it inside out. The point of your nose, which was pointing into the mirror is now pointing out of the mirror. The parts of you that are nearest the mirror are also nearest in the reflection. Your entire image has been turned inside out.

In reality there is no swapping of left and right, so you don’t have to explain why the mirror handles this differently from top and bottom. The reason we have the illusion of a left-right switch is down to your brain. When you see your reflection in a mirror your brain tries to turn the reflection into you. It makes a fairly close match if it rotates you through 180 degrees and moves you back into the mirror. This half turn flips left and right. But the key thing to realise is that it’s not the mirror that performs a swap of left and right, it is your brain, trying to interpret the signals it receives from the mirror.

Now, with the mirror’s mystery solved, let’s start our exploration of the universe by taking a look at a single, rather unusual part of your body. We are going to investigate a human hair.

2. A single hair

Take a firm hold of one of the hairs on your head and pull it out. No one said science was going to be entirely painless. If you want to make this less stressful, get a hair from a hairbrush. If you are bald, get hold of someone else’s hair – but ask first! Now, examine what you’ve got. It’s a long, very narrow cylinder, flexible yet surprisingly strong considering how thin it is.

Take as close a look at the hair as you can. If you can lay your hands on a microscope, use that, but otherwise use a magnifying glass.

That strand of hair is going to start us off on everything from philosophy to physics. Dubious about just how philosophical hair can be? Consider this: you are alive and that hair is an integral part of you (or at least it was until you pulled it out). Yet the hairs on your body are dead – they are not made up of living cells. The same is true of fingernails and toenails. So you are alive, but part of what goes to make ‘you’ is dead.

Remember that next time a TV advert is encouraging you to ‘nourish’ your hair. You can’t feed hair. You can’t make it healthy. It’s dead. Deceased. It has fallen off its metaphorical perch. Worried that your hair is lifeless? Well, don’t be. That’s how it is supposed to be. It’s quite amazing just how many hair products are advertised using the inherently meaningless concept of ‘nourishing’.

We’re talking about a single hair, but of course you have (probably) got many more than one on your head. A typical human head houses around 100,000 hairs, though those with blonde hair will usually have above the average, and those with red hair rather fewer. Looking at that individual hair, the colour that provides this distinction doesn’t stand out the same way it does on a full head of hair, but it’s still there.

The colours of nature

The colour in hair comes from two variants of a pigment called melanin. One, pheomelanin, produces red colours. Blonde and brown hair colourings are due to the presence of more or less of the other variant of the pigment, eumelanin. This is the original form of hair pigment – red hair is the result of a mutation at some point in the history of human development.

As we become older, the amount of pigment in our hair decreases, eventually disappearing altogether. Grey and white hairs don’t have any melanin-based pigment inside. In effect they are colourless, but the shape of the hair and its inner structure has an effect on the way that the light passes through it, producing grey and white tones.

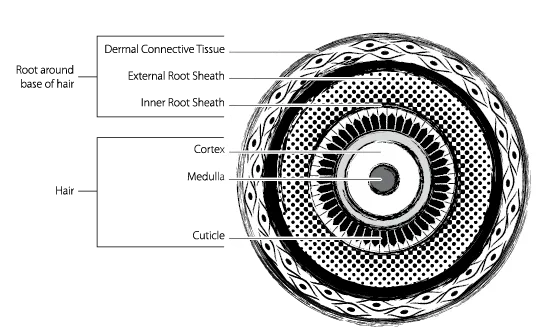

Cross-section of a human hair

The inner structure of hair isn’t particularly obvious when you hold a single strand in your hand and look at it with the naked eye, but under a microscope it becomes clear that there is more going on than just a simple filament of uniform material. In effect your hairs have three layers: an inner one that is mostly empty, a middle one (the cortex) that has a complex structure that holds the pigments and can take in water to swell up, and an outer layer called the cuticle which looks scaly under considerable magnification, and which has a water-resistant skin.

On the end of the hair, where you have pulled it out of your scalp, there may be parts of the follicle, the section of the hair usually buried under your skin. The follicle is responsible for producing the rest of the structure and is the only part of the hair that is alive.

Dyeing to be attractive

The idea that the colouring of your hair is produced by melanins assumes it has its natural hue, but many of us have changed our hair colour using dyes at one time or another. Dyes use a surprisingly complex mechanism to carry out the superficially simple task of changing a colour. It’s not like slapping on a coat of paint – the process of dyeing hair owes more to the chemist’s lab than the beauty salon.

In a typical permanent dyeing process, a substance like ammonia is used to open up the hair shaft to gain access to the cortex. Then a bleach, which is essentially a mechanism for adding oxygen, is used to take out the natural colour. Any new colouration is then added to bond onto the exposed cortex. Temporary dyes never get past the cuticle; they sit on the outside of the hair and so are easily washed off.

Worrying about hair loss

Almost every human being has hairs, but compared with most mammals we are very scantily provided. Not strictly in number – we have roughly the same number of hairs as an equivalent-sized chimpanzee – but the vast majority of these hairs are so small as to be practically useless.

Next time you are cold or get a sudden sense of fear, take a look at the skin on your arms. You should be able to see goose bumps or goose pimples. This hair-related (indeed, hair-raising) phenomenon links to the fact that our ancestors once were covered in a thick coat of fur like most other mammals.

When you get goose bumps, tiny muscles around the base of each hair tense, pulling the hair more erect. If you had a decent covering of fur this would fluff up your coat, getting more air into it, and making it a better insulator. That’s a good thing when you are cold, at least if you have fur – now that we’ve lost most of our body hair, it just makes your skin look strange without any warming benefits.

Similarly, we get the bristling feeling of our hair standing on end when we’re scared. Once more it’s a now-useless ancient reaction. Many mammals fluff up their fur when threatened to make themselves look bigger and so more dangerous. (Take a dog near to a cat to see the feline version of this effect in all its glory. The cat will also arch its back to try to look even bigger.) Apparently we used to perform a similar defensive fluffing-up, but once again the effect is now ruined by our relatively hairlessness. We still feel the sensation of having our hair stand on end, but get no benefit in added bulk.

Our lack of natural hairy protection struck me painfully when out walking my dog recently. It was a cold day and I was under-dressed for the weather in a short sleeved shirt. I was shivering and my trainers were soaked from the wet grass, so that I squelched as I walked. When passing through the fence from one field to the next, I ma...