![]()

Part I

Illuminations:The Light of Reason

Why are the nations of the world so patient under despotism? Is it not because they are kept in darkness and want knowledge? Enlighten them and you will elevate them.

Reverend Richard Price, A Discourse on the Love of our Country, 1789

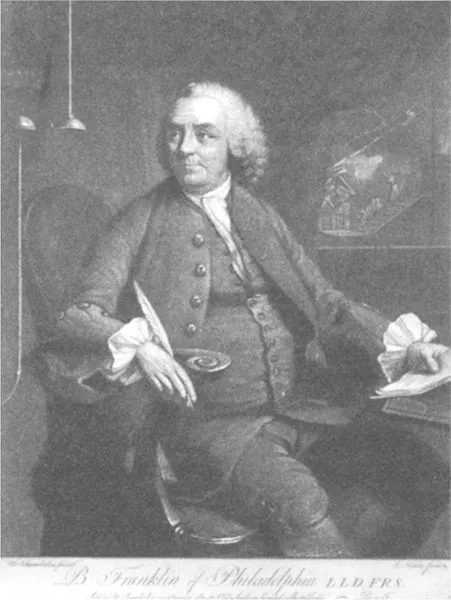

For many years, Franklin’s favourite portrait of himself was the one shown in Illustration 1, which had been painted in London in 1762 and engraved the following year. Following English conventions for portraying Enlightenment men of letters, Franklin is shown working in his study, his quill and paper prominently displayed to advertise his intellectual solidity. Clearly absorbed, he is listening to the electric bells behind his right shoulder, from which hang two electrified, mutually repellent cork balls. To his left, the traditional draped curtain is drawn back to reveal an imaginary composite scene, in which the devastating effects of lightning are contrasted with the protective security afforded by Franklin’s most famous invention, the lightning rod.

Illustration 1: ‘Benjamin Franklin’, mezzotint by Edward Fisher after Mason Chamberlin, 1763. (Wellcome Institute)

It was this picture that Franklin chose as a gift for his close friends and colleagues, and to impress remote government contacts in America. With the help of his son William, he sent out over one hundred copies, carefully rolling each one up in a protective tin case. Distributing pictures in this way enabled Franklin not only to boast about his electrical prestige, but also to solicit political support and consolidate personal friendships.

Beneath the engraving, the inscription ‘B. Franklin of Philadelphia LLD FRS’ makes it clear that Franklin was a distinguished scholar; moreover, it advertises that he was an American, the first President of the American Philosophical Society. As the colonies struggled for independence, nationalists enthusiastically vaunted specifically American achievements, hymning Franklin as the new nation’s challenge to Isaac Newton. Poets gushed about this electrical expert whose political initiatives had guaranteed the political freedom necessary for scientific rationality to flourish:

![]()

1 Interpretations

Franklin has become a hero not only for patriotic Americans, but also for scientists who want to tell dramatic stories about the discovery of electricity. Modern society depends on scientific and technologic achievements, but there are several different ways of describing how science has become so important.

Many historians envisage science as a progressive success story, a continuous march towards learning the truth about the natural world. They construct heroic models of the past in which exceptionally gifted men (and the occasional woman) build on the insights of their predecessors to make great advances. Achievements that may have taken years of effort are converted into picturesque adventures – Archimedes shouting ‘Eureka!’ from his bath, Isaac Newton sitting under an apple tree, James Watt watching a kettle boil. In these versions of science’s history, Franklin appears as the great electrical champion who bravely conducted electricity down to earth by flying a kite.

Such memorable tales are appealing because they glamorise scientific research, but they present a misleading and over-simplified picture. Writers often smooth away conflicts, confusion and ambition, portraying scientists as disinterested searchers after truth, dedicated investigators who are unaffected by the normal demands of human life. Many scientists are, of course, genuinely concerned not only to discover more about the world, but also to bring about useful improvements. But they can also be competitive people who want to earn money, become famous and defeat their rivals. Despite the enthusiastic claims of Enlightenment experimenters, there was no easy upward path of progress, and research was fuelled by hostility as well as by curiosity.

Scientific experiments aren’t always successful: people make mistakes, ignore results that later seem significant, or persuade themselves – and others – to adopt theories that turn out to be false. Just as importantly, science’s accomplishments are not due to the single-handed efforts of a few geniuses. With the benefit of hindsight, it is relatively easy to pick out key individuals and events that seem to have directed the course of history. But singling them out means forgetting about the countless other projects that were being undertaken at the same time.

Franklin is central to any story of Enlightenment electricity, but he was just one player in a complex tale of change that had many other participants – Joseph Priestley in England, Jean Nollet in France and Luigi Galvani in Italy, to name just a few. Franklin became interested in electricity only after he had read about other people’s inventions, and his own innovations were adapted and improved by his successors. Even the story of his kite has been embroidered into a myth; in reality, some French experimenters were the first to show that lightning is electrical by drawing it down from the sky.

Science, politics and society were inextricably linked. When Franklin was eighty-one years old and helping to draft the American Constitution, an eminent English doctor sent him a flattering letter in which he wrote: ‘Whilst I am writing to a Philosopher and a Friend, I can scarcely forget that I am also writing to the greatest Statesman of the present, or perhaps of any century, who spread the happy contagion of Liberty amongst his countrymen; and … deliver’d them from the house of bondage, and the scourge of oppression.’5 Franklin’s interest in electricity was rooted in this Enlightenment political ideology, and that is where this version of electricity’s history will begin.

![]()

2 Electricity and Enlightenment

In the second half of the eighteenth century, there were only two English universities – Oxford and Cambridge. Both were expensive, closed to women, and better at training young men to become clergymen than scientific practitioners. Like Franklin himself, many people learnt about electricity by reading journal articles and attending lectures. One of the more successful popular scientific books was called The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Philosophy, indicating that – unlike its heavier rivals – it was designed for women as well as for men.

The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Philosophy uses dialogue, a traditional teaching method dating back to the Greeks. An elegantly dressed student, burdened with the appropriately classical-sounding name of Cleonicus, returns from university to play the superior role. He engages in long conversations with his envious sister Euphrosyne, who has been confined at home to study suitably feminine subjects such as drawing and dancing. In each chapter, the knowledgeable Cleonicus patronisingly explains the rudiments of a different branch of natural philosophy, the study of nature. By using terms so simple that even she can be expected to understand them, this artificial dialogue implicitly advertises that natural philosophy can be understood by everyone.

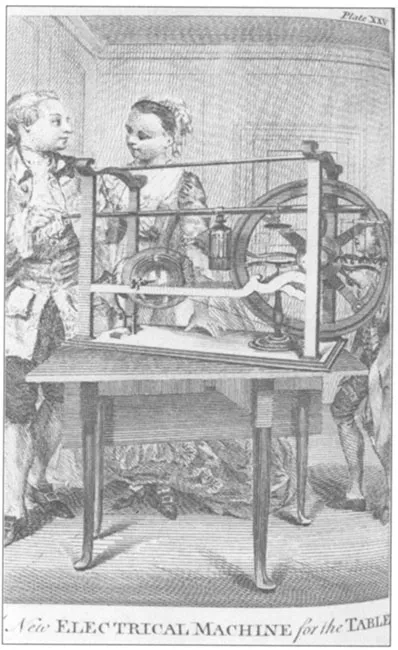

One day, after a lengthy session on the weather, Cleonicus agrees to explain how lightning and thunder are related to the exciting new science of electricity. Leading his sister into a shuttered room, he prepares to demonstrate a recent invention conveniently placed in their well-appointed home – an electrical machine (Illustration 2). Cleonicus is confident that with the help of this machine, he can dazzle his sister with dramatic effects of light and sound totally different from anything she has ever encountered before.

Illustration 2: ‘A New Electrical Machine for the Table’. Benjamin Martin, The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Philosophy, 2 vols, London, 1759–63, vol. 1, facing p. 301. (Cambridge University Library)

Writers of this period delighted in using elaborate puns, and these references to light and dark allude not only to the physical surroundings of this young couple, but also to their intellectual and spiritual illumination. French philosophers declared that they were living in the ‘Siècle des Lumières’, the ‘Century of Lights’, and this was indeed the time when Europe’s cities started to be brightly lit. London’s citizens were among the first to install hanging glass lanterns that shone all night – one German prince even thought that the splendid display had been especially prepared to honour his visit. Cleonicus’ electrical sparks and flashes were a smaller, homespun version of the dramatic firework shows so beloved by wealthy party-givers.

Seeing was closely allied with knowing. Progressive thinkers often claimed that they were living in an enlightened age, when the bright flame of reason would dispel the dark clouds of ignorance and superstition. Yet this was also a profoundly Christian society, and religious imagery of divine light still pervaded literature and art. Through learning about electrical light, Cleonicus is arguing, Euphrosyne will gain an enlightened mind, the rational, secular equivalent of a soul inspired by the Light of God.

The period from roughly 1730 to 1790 is often loosely referred to as ‘the Enlightenment’. During this period, many writers declared that rational thought would sweep away old errors and superstitions; reason would guarantee material and intellectual progress, as well as political liberty and freedom of thought. Faith in the Bible as the unique source of truth should, they insisted, be replaced by confidence in knowledge about the physical world gained by natural philosophers. Rather than relying on Aristotelian logic (which was often referred to as ‘the teaching of the schools’), people should learn through experiment and reason. The Scottish philosopher David Hume recommended ritual book-burning:

One of the most famous Enlightenment philosophers was François-Marie Voltaire, who declared triumphantly that ‘the spirit of the century … has destroyed all the prejudices with which society was afflicted: astrologers’ predictions, false prodigies, false marvels, and superstitious customs’.8 In accordance with Voltaire’s boast, the Enlightenment came to mean the time when scientific, quantitative methods were successfully introduced. Often dubbed ‘the Age of Reason’, the Enlightenment is traditionally celebrated as the birth of modern civilisation, which took place primarily in France.

But it is time to rewrite the history of the Enlightenment. Rationality no longer seems such an unquestionable virtue, since spiritual and mythological approaches also have many insights to offer. There was no universal modernising spirit that swept across Europe, as though the electric light of reason had suddenly been switched on. Rather, the Enlightenment period was characterised by intellectual dissent, national differences and a persistent esteem for the past.

The roots of the Enlightenment lie further back than 1730, and England was also the home of enlightened values. As early as 1706, the third Earl of Shaftesbury proclaimed that ‘there is a mighty Light which spreads its self over the world especially in those two free Nations of England and Holland; on whom the affairs of Europe now turn … it is impossible but Letters and Knowledge must advance in greater Proportion than ever … I wish the Establishment of an intire Philosophicall Liberty.’9 When Voltaire was forced into exile in 1726, it was England that he chose as his place of refuge. Partly to criticise affairs in France, he lavishly praised English practices, politics and people. In particular, he singled out Newton, marvelling that such a dedicated scholar ‘lived honoured by his compatriots and was buried like a king who had done well by his subjects’.10

Newton’s work was vital for the claims made by enlightened philosophers that reason should reign supreme. Science is central to modern society, but the word ‘scientist’ was not even coined until 1833. Newton and his followers were known as ‘natural philosophers’ because they taught that knowledge could be gained by examining the natural world. They were trying to reconcile God’s two books: the Bible and the Book of Nature. Deciphering God’s blueprint for the world was, they argued, the surest route to learning more about God, as well as to improving human welfare.

Three centuries ago, natural philosophers did not enjoy the prestigious status of modern scientists. Gulliver’s Travels is a particularly famous example of hostility towards scientific projects. In this complex satire, first published in 1726 (the year before Newton died), Jonathan Swift poked fun at inventors by portraying them foolishly trying to make sunbeams out of cucumbers, or build houses from the roof down. Faced with such attacks, natural philosophers struggled to justify themselves by demonstrating that their results were useful and reliable. Science had not been established as a professional career, and although many natural philosophers were independently wealthy, others needed to invent new ways of earning money from their activities. Innovative entrepreneurs gave lectures, wrote books, and devised instruments that would not only test their theories, but also attract paying spectators who, it was hoped, would admire their skills and recognise their control over the powers of nature.

Of all the branches of natural philosophy that would eventually become modern scientific disciplines, the most popular was the study of electricity. Many of the early investigations took place in England, but interest quickly spread abroad. Especially during the second half of the eighteenth century, electrical experiments dominated meetings at learned institutions such as the Royal Society in London and the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris.

In The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Philosophy, Cleonicus performed for his sister’s benefit, but his readers provided a large virtual audience. He excelled in the theatrical techniques essential for Enlightenment lectures, which were entertaining performances as much as educational demonstrations. Delighting in arousing his sister’s bewildered admiration, Cleonicus generated circles of fire, ignited gunpowder and illuminated fountains of water. Maliciously teasing her delicate sensibility, he wired up her dog and enrolled his servant to act as electrical executioner to a small bird.

But Cleonicus was also concerned with more serious matters, applying his skills to investigate both the nature of electricity and the uses to which it could be put. For instance, he replicated lightning inside their house, and explored the possible medical benefits of delivering shocks to different parts of the body. Although fictional, Cleonicus behaved like many experimental demonstrators who believed in teaching through entertainment. Enlightenment philosophers wanted not only to discover natural laws, but also to promote themselves by displaying their command of apparently inexplicable phenomena such as electricity.

One of England’s most famous electrical experts was Josep...