![]()

PUCCINI

ONE OF THE first musical ‘events’ of the 20th century was the première of Tosca in Rome on 14 January 1900. It was magnificent theatre, and a great 19th-century opera. Organisers of events to mark the turning of centuries and similar jubilees would be hard pressed to find anything better to stage: a simple, straightforward drama, with a big spectacle. It provided an opportunity for Puccini to write some of his best and most memorable songs, such as ‘Vissi d’Arte’ and ‘E Lucevan le Stelle’. Anyone hearing it would surely agree that ‘where erotic passion, sensuality, tenderness, pathos and despair meet and fuse, he was an unrivalled master’.1 Yet, Puccini’s name does not appear in the index of Alfred Einstein’s leading work on Music in the Romantic Era written just after the Second World War.

So where does he fit in? Although traces of Tristan, Debussy and the whole-tone scale are detected in some of his works, Puccini is hardly a 20th-century composer: Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was premièred in May 1913, over a decade before Turandot.

Most composers have damned him. Stravinsky dismissed Madame Butterfly as ‘treacly violin music’.2* Fauré labelled La Bohème a ‘dreadful Italian work’4 and Richard Strauss said that he could not distinguish between it and Butterfly.5 The leading Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini put his finger on the problem: ‘In many Puccini operas you could change the words, and any other set would do.’6 Of the Paris première of Tosca in 1903, Fauré wrote to his wife: ‘At the very beginning of September there will be an important première at the Opéra-Comique; important because of the personality of Sardou, the librettist, and the bizarre school of music to which the composer of the music belongs, Puccini. They consist of three or four fellows who have conjured up a neo-Italian art which is easily the most miserable thing in existence; a kind of soup, where every style from every country gets all mixed up. And everywhere, alas! they are welcomed with open arms.’7

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that, as far as Broadway and the West End was concerned, Puccini was 20th-century in his skill with the voice and with melody, in his soft harmony and gentle orchestration, and most particularly in his remuneration. A Decca recording presenting the great moments in opera performed by the world’s leading artists includes six items by Puccini, far ahead of the others. There are only two each from Wagner, Donizetti and Verdi. Trailing behind are Rossini, Mozart, Bellini, Bizet and Offenbach, each with one item to represent them.8 The composer of ‘Your tiny hand is frozen’ from La Bohème and ‘One fine day’ from Madame Butterfly looks well placed to survive the test of time. ‘Nessun dorma’ from Turandot was the theme music for the 1990 Football World Cup. Few could deny that Puccini wrote very effective and tremendously enjoyable music.

As a person, however, apart from Janá

ek, Puccini is possibly the least likable of all the composers described in this book. But, as a loyal supporter said of Janá

ek, ‘his contribution to the arts is so great that it outweighs any flaws in his character’.

9 Puccini’s self-centred personality benefited from an attractive raffishness absent in Janá

ek’s. Success, measured by prodigious remuneration, went to Puccini’s head. His ‘melancholia demanded relief in violent sex, slaughtering birds and driving high-powered cars at reckless speed’.

10 Perhaps he summed himself up quite well when he said: ‘I am a mighty hunter of wildfowl, beautiful women and good libretti.’

11Puccini was not initially as successful as his contemporaries Leoncavallo and Mascagni, but he quickly outshone them and took his place alongside Massenet, who inspired his style. We shall look briefly at Massenet before observing Puccini create the operas which brought him such fame. We shall also look at the sordid tragedy of Doria Manfredi, a real-life story to equal that told in any of his operas.

EARLY YEARS

Giacomo Puccini was born around 22 December 1858, in Lucca, the birthplace of Boccherini. About thirteen miles from Pisa, Lucca is an old walled town, with narrow streets, and boasts a Roman amphitheatre.

Giacomo’s birth brought to five the number of generations of musicians in Puccini’s family. One biographer has gone so far as to say that the Puccinis rank only after the Bachs in the order of families ‘in which a creative gift for music was hereditary’.12 Puccini’s great-grandfather was a member of the Accademia Filarmonica of Bologna and may well have been present when Mozart was admitted in 1772. Puccini’s grandfather, Domenico, had written Il Trionfo di Quinto Fabio, an opera which had been commended by Haydn’s contemporary, Giovanni Paisiello.13

The family effectively possessed the hereditary right to the post of organist and choirmaster of Lucca’s cathedral of San Martino, with its altarpiece by Tintoretto and a relic, the Sacred Countenance, said to be carved by Nicodemus.14 Giacomo’s father died when he was five. His mother, who was eighteen years younger than her husband, had once been his father’s pupil. She was now left to bring up Giacomo, his younger brother and five sisters on a tiny pension from the city council.15

Puccini studied with his uncle, who was keeping the organ seat warm until he came ‘of musical age’. He gained a broad experience: he sang in the choir, worked part-time at a casino, and provided music for both a convent and a bordello.16 He smoked from an early age and began his water-fowling career on the Lago Massaciuccoli, which is a few miles over the hills from Lucca. When he needed money, he stole and sold the organ pipes from a village church in which he accompanied the services: he could easily alter the harmonies so as to conceal his theft. A walk to Pisa to see Verdi’s Aïda inspired him to go to the Milan Conservatoire,17 which he eventually did, in September 1880, financed by a bursary, augmented by a loan from a great-uncle, who was a prosperous bachelor.18

In Milan, he survived on thin minestrone, tobacco and the occasional visit to the cafés in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele. One of his teachers at this time was Amilcare Ponchielli who had composed I Promessi Sposi and the very popular La Gioconda.

Puccini’s brother joined him in Milan as did Pietro Mascagni, who was some five years younger. Mascagni, the son of a Livorno baker, was expelled from the Conservatoire after two years for lack of application; he had to turn to playing the double bass and conducting third-rate operetta companies.19 Puccini graduated with an exercise, the Capriccio Sinfonica, which showed his talent for melody and colourful orchestration.

The poor quality of musical performance in Italy at the time is indicated by Tchaikovsky: ‘A scoundrel conductor. Despicable choruses. In general everything is provincial. Left after the second act.’20 He described ‘the ludicrously stout singer with a voice like a huckster’s’, adding that ‘this time the orchestration of Aïda seemed vilely coarse to me in places’.21 Then for I Puritani: ‘the singing not bad, but the orchestra and production awful’.22

A crucially important person in Milan musical circles was Giulio Ricordi, who ran his family’s publishing house, which owned the copyright in virtually every opera produced in Italy. The Ricordi business had branches throughout Europe, the USA and Latin America. His grandfather, a copyist at La Scala, had started the business and had acquired the copyright in the works of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti and then Verdi.23 A wealthy industrialist and newspaper magnate, Edoardo Sonzogno, decided to challenge Ricordi’s monopoly, so he sponsored a competition for a one-act opera.24 The prize was 2,000 lire.* Puccini entered with Le Villi (the witches), but did not win, possibly because his entry, like so many of his later compositions, was almost illegible.

Another person with great influence was Arrigo Boito, soon to be celebrated as the librettist of Verdi’s Otello and Falstaff. Puccini played Le Villi on the piano at a salon at which Giulio Ricordi and Boito were present. They were so impressed that they decided to stage it. Ricordi suggested some changes,26 and it was a great success. Boito, who was working on Otello, introduced Puccini to Verdi.

Ricordi then commissioned another opera using Fontana, the librettist of Le Villi. The newspaper Corriere della Sera was ecstatic: ‘In a word, we believe sincerely that in Puccini we may have the composer for whom Italy has long been waiting.’27

Puccini was frequently invited to dine at the house of a former schoolmate, a prosperous merchant in olive oil, coffee, spices, wines and spirits. There, he would play duets with Elvira, his school friend’s wife. She was tall, majestic and had a very slim waist.28 Puccini, for whom ‘conquests were easy and numerous’,29 quickly cuckolded his friend, and Elvira joined him, abandoning her baby, but bringing her daughter Fosca with her. Their son Antonio was born on 23 December 1886, when Puccini was just 28.30

It was a difficult time for him: the people of Lucca were scandalised by his behaviour; he was greatly in debt to Ricordi; and he was hounded by landlords. His great-uncle observed that, if he could afford to keep a mistress, he could afford to pay back the money which he had given him. Edgar, the opera which Ricordi had commissioned, was not a success. * After this, Puccini thought of emigrating to Argentina, but his brother put him off: he himself had gone there and was finding it impossible to make ends meet. But the experience with Edgar taught Puccini an important lesson: the composer must be absolutely ruthless about the quality of his libretto.

MASCAGNI AND LEONCAVALLO

Then Mascagni was suddenly propelled to fame. After years of hardship, and having been rejected by Ricordi, he entered for Sonzogno’s second contest for one-act operas in 1888. He intended to submit an opera called Guglielmo Ratcliff, but his wife entered the recently completed Cavalleria Rusticana, without his knowledge. When it was put on in 1890, it was ‘a hit if there ever was one’,31 and Mascagni was instantaneously world famous. In Belgrade, the whole work had to be repeated before a hysterical audience would leave the theatre.**32

Puccini, meanwhile, worked slowly and laboriously on Manon Lescaut. The libretto was being written by Ruggiero Leoncavallo, a café pianist and would-be composer, who had fallen on hard times.† But Puccini was not at all happy with Leoncavallo’s draft, and turned instead to a couple who would serve him well in the future: Luigi Illica, an author of light comedies, and Giuseppe Giacosa, a prominent playwright, who lectured on drama at the Conservatoire. Leoncavallo stormed off in a huff. In what must have been a particularly galling experience for Puccini, Leoncavallo then composed I Pagliacci, which was inspired by a murder trial over which his father had once presided as a police magistrate.33 When Ricordi rejected Pagliacci, Sonzogno scooped it up. When premièred under the young Toscanini in May 1892, it was a colossal success.

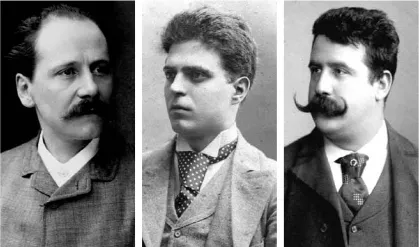

Jules Massenet / Pietro Mascagni / Ruggiero Leoncavallo

With Puccini seeming to be unsuccessful and having difficulty making ends meet, Elvira became jealous of Mascagni’s and Leoncavallo’s success and their purchasing power. She became increasingly difficult, and went off to live in Florence with her sister. Puccini returned to Torre del Lago, a small village of fishermen and bohemian painters, located between the sea and the shallow reedy Lake Massaciuccoli, where he had poached as a boy. There, he took one of the hunting lodges rented by weekend sportsmen to shoot wild duck and moorhen. Elvira eventually returned to join him there. Their difficult relationship was well expressed in the comment: ‘Theirs was the almost classic dilemma of an abnormally sensual and egocentric couple, who could not live in harmony for long periods, but found it even more intolerable to stay apart.’34 One of Puccini’s last words on his deathbed was to tell his step-daughter: ‘Remember your mother is a remarkable woman.’35

Puccini, by now aged...