![]()

1 Seven Billion and Counting

‘The constant effort towards population, which is found even in the most vicious societies, increases the number of people before the means of subsistence are increased.’

Thomas Malthus, essayist

On 30 October 2011 the world welcomed its seven-billionth citizen: Danica May Camacho, a Filipina, born in the early hours of the morning at the Dr Jose Fabella Memorial Hospital in Manila. She was chosen by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to officially mark this milestone and draw attention to the economic, social and practical challenges of managing the world’s rapidly growing population.

The fact that these challenges require such a grandiose PR stunt to make them newsworthy at all is testament to the fact that we find them so easy to ignore. For most of us, the Official Day of Seven Billion was a story to be forgotten as soon as the agenda moved on to something else. Danica May Camacho herself, briefly the most famous baby in the world, is likely to live out the rest of her life in the obscurity endured by twelve-year-old Adnan Nevic of Bosnia Herzegovina and Matej Gaspar, a 24-year-old Croat, respectively the world’s six- and five-billionth inhabitants. It’s easy to understand our indifference. On first inspection, there seems very little truly new to say on the subject. The quote from Thomas Malthus that opens this chapter sounds like it could have been uttered last week rather than 1798. This is because the fundamental issue remains the same: too many people/not enough resources. One could be forgiven for thinking that little else has changed since Malthus penned his Essay on the Principle of Population; the same dire warnings about famine and drought, the same apocalyptic forecast of global wars that will bring about the collapse of civilisation, and the same list of unspeakably miserable consequences for us all: none of which has come to pass. However, this scepticism is misplaced.

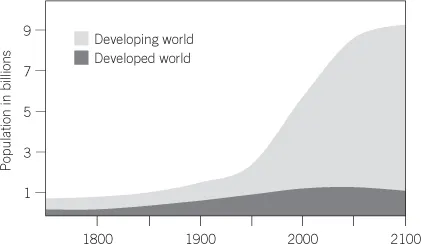

Fig. 1: World population growth since 1750. (Source: UNFPA)

It is true that all our lives have played out through a period of explosive population growth, but that doesn’t stop it being extraordinary. Indeed, this is also the only period of explosive population growth in human history. We have taken just 84 years to go from 2 billion to 7 billion earthly inhabitants and, unless we take some decisions about how everyone is going to have to live, we will soon reach a point where the global population becomes unsustainable. While forecasting is a notoriously contentious and difficult discipline, among those who are looking to the future there is a consensus that global population will continue increasing until the middle of the century, at which point it will peak and plateau at somewhere around 10 billion. From less than 2 billion to 10 billion people in little more than a lifetime; the blink of an eye when set against the 200,000 years that our species, Homo sapiens, has been on the planet.

It’s tempting to believe that a simple presentation of the facts will be enough to shake us from our complacency. Certainly, one would assume that was the rationale of the UNFPA when it conceived the idea of Citizen Seven Billion, but unfortunately there’s more to our indifference than this. It’s not just that over-familiarity makes this story easy to ignore, it’s that most of us choose actively to ignore it. We feel reassured by the trappings of our advanced society with its central heating, running water, supermarkets, ready meals and fuel-injected cars; at a comfortable remove from the sources of food and energy. Yet despite our apparent sophistication, in evolutionary terms we have barely set foot out of the forest. We are the same nervous, skittish creatures that were once hunted mercilessly by leopards, wolves and cave bears, with the same reactions to fear and danger.

While we have the intellectual capacity to think about the future and ponder, ‘What might happen if …?’, we are much more focused on the present; driven by today’s needs rather than tomorrow’s consequences. As a result we have evolved to be remarkably good at ignoring ‘What might happen if …?’, especially if we suspect that thinking about it might prove terrifying. The smoker enjoying the first cigarette of the day; the commuter racing down the motorway at 85mph and the student choosing an evening out over a night of revision, are all aware of the possible consequences of their actions at a nebulous point down the line (lung cancer, a car crash, examination failure) but that only makes them easier to disregard. We treat these as things that will happen to other smokers, other drivers and other revellers, not to us. In these cases and many others, this wilful ignorance is bliss. We behave in exactly the same manner when confronted by less personal or unspecific dangers; it’s really just a question of the scale of our denial.

As far as threats with terrifying, immeasurable consequences go, global warming takes some beating. In 2007, Al Gore visited Sheffield to host a conference on climate change. We were fortunate enough to receive an invitation to attend. Whatever your political views, there’s no denying that Al Gore is a very capable and engaging public speaker. Over the course of 90 minutes, the former US Vice President performed a live version of his Oscar-winning documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, during which he clearly laid out all the evidence for human influence on global climate change and explained its consequences. His compelling argument and powerful delivery certainly made for a fascinating lecture, but also for one of the most dispiriting things we have ever seen.

Gore had two stated objectives for An Inconvenient Truth. He wanted to leave audiences believing that global warming is the biggest issue, but he also wanted to persuade them to change their behaviour by making them believe that doing so could help to reverse its effects. To that end, he concludes the film with the following call for action:

Each one of us is a cause of global warming, but each one of us can make choices to change that with the things we buy, the electricity we use, the cars we drive; we can make choices to bring our individual carbon emissions to zero. The solutions are in our hands, we just have to have the determination to make it happen. We have everything that we need to reduce carbon emissions, everything but political will.

While there’s little doubt that he achieved his first objective, he has been much less successful in changing our behaviour. For a week or so following the live lecture, we felt deeply depressed about not only the future, but the futility of our own efforts to reverse the effects of global warming (switching to low-energy light-bulbs, unplugging electrical appliances when not in use, driving at 60mph instead of 70mph – that sort of thing) in the face of the two coal-burning power stations that were being opened in China each week. Within a fortnight, however, we were back to our usual chipper selves, thanks not to thinking of creative solutions to reduce our own carbon footprint, but simply to not thinking about it at all.

Of course ignoring the problem isn’t going to make it go away, but then neither will worrying about it. The most frustrating aspect of all the challenges we face – not just climate change and population growth, but food and energy sustainability as well – is that we already have almost all of the science and technological solutions required to avert disaster; what we lack is the social and political will to implement them. Moreover, if a combination of complacency, fear, and wilful ignorance makes it difficult for us to motivate ourselves and our politicians towards effective action, conversely it provides a fecund opportunity for those wishing to persuade us, however disingenuously, that everything is going to be all right.

One doesn’t have to look very hard to find climate change ‘sceptics’ who focus on minor flaws in the science that ‘undermine the entire argument’. Just because there are naysayers doesn’t mean there needs to be a debate. For example, despite all evidence to the contrary, if you type ‘smoking doesn’t cause cancer’ into Google, your search will yield 143,000 results, all purporting to prove that it doesn’t.

It is noteworthy that almost all the scepticism about climate change comes from the conservative right. Surely if the data was so equivocal, one would expect dissenters across the political spectrum? Yet, for whatever reason, this is not the case. The binary nature of most media outlets – where arguments for and against an issue are given equal weight, regardless of their legitimacy – means that outliers often find a platform for their views that is vastly disproportionate to their credibility. Their cause is furthered by the fact that their claims are much closer to what most people want to believe is true, namely, that the status quo will be maintained and modern life will carry on regardless. It’s certainly what we’d like to believe is true too, but unfortunately, in the face of all the evidence, that is impossible to do.

Our fear of change prevents the adoption of potentially life-saving technologies such as nuclear power, concentrated solar energy and genetically modified plants and animals. We can argue about how much oil is left until finally someone is right and there isn’t enough; and we can argue about whether to genetically modify crops until there’s nothing left to eat. Alternatively, we can act now.

We will certainly reach a point from which it will be impossible to recover, but we are not there yet. It really doesn’t need to end unhappily. And now for the good news – there is something that we can do about it.

Science and technological innovation have driven global prosperity. Since the Enlightenment of the 18th century they have proved consistently capable of meeting the ever-increasing demand for energy and food. In the past 40 years alone, the amount of land used for agriculture has increased by only 8 per cent, while food production has doubled. This success is almost entirely due to chemical and biological breakthroughs and innovations: providing more effective pesticides and fertilisers; improving crop and meat yields through breeding programmes. We must ensure that the fruits of this process of invention are sustainable.

The challenges we face in the next 40 years are complex and difficult, but they are not insurmountable. A study published in January 2011 by the UK’s Institution of Mechanical Engineers suggested there are no scientific breakthroughs required to manage a global population of over 10 billion people:

There is no need to delay action while waiting for the next greatest technical discovery or breakthrough idea on population control … [There are] no insurmountable technical issues in meeting the basic needs of nine billion people … sustainable engineering solutions largely exist.

There are key areas that we need to focus on to ensure food security. The huge improvements in crop yields have to continue, but they are eminently deliverable. We must make less profligate use of our fresh water supplies; and develop genetic solutions to crop protection and rely much less on chemical fertilisers and pesticides. We need to develop a system of agriculture that is holistic, part of the richer ecosystem rather than the wilfully imposed cereal monoculture we have today that operates outside it. Livestock and marine food production can continue only within the context of sustainability. We can also make a big difference by choosing to live less wasteful lifestyles: currently in the developed nations, over a third of all food that is harvested is simply thrown away.

It is naive to suggest, as some learned commentators have done in the past, that tens of millions of African farmers could triple yields with existing crops if only they could afford fertiliser. The global fertiliser crisis might not be the most captivating challenge humankind is facing at the moment, but it is arguably the most important. Oil is an integral part of modern agriculture, accounting for 3 per cent of the global energy budget. Almost all of this oil is used, not for transportation as many people think, but in the production of synthetic fertiliser. We need to be decreasing not increasing our reliance upon synthetic fertiliser. A more sensible strategy is to stop wasting so much of the harvest and seek alternative means of increasing crop yields. And we should be doing this not just in Africa either, but across the whole world.

Providing energy security is rather more complex, particularly because almost all of the fuels we use presently are the major contributors to climate change. We have around two decades to de-carbonise electricity generation, which will require significant investment in emerging technologies and processes. Achieving holistic solutions will require scientists from different disciplines working together across traditional boundaries.

The Solar Revolution is the story of how we are going to provide sustainable food and energy for a global population of 10 billion people. The answers lie in a range of ongoing research across many disciplines: from solar physics, photovoltaics and photosynthesis to plant physiology, biochemistry and ecology. This research is typically disparate, very detailed and difficult to digest. We will provide a real solution only by pulling it all together and putting it into context. This book aims to do exactly that.

Almost 100 per cent of our energy comes from the sun.1 We need to understand how the sun works, how it provides us with that energy, and learn how to use some of it to power everything that happens on Earth in real time, rather than relying on the unrenewable stores of ancient sunshine buried in coal, oil and gas. In part, this is about unlocking the mysteries of electrons, molecules and genetics, but we also need to take a much grander view, to understand how carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous are traded on a global level. And so our quest will begin and end with mathematics and theoretical physics. By bringing the many pieces of research together and synthesising them, we can get a true picture of how we are going to live – and going to have to live – in the future. There’s no point in worrying. The future is going to be very different, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be scary, or even worse. There’s no reason to fear that you’ll be living out a real-life version of The Road any time soon.

To show how we can safeguard the future we need to understand how our world became the place it is today – chemically, geologically, ecologically, climatically and economically. We need to understand where all our food and energy comes from, to help us decide what we need to live and what we can live without. Among all the animals, we have the unique ability to change the environment for the benefit of the species, but if humankind is to survive and prosper we will have to do this more effectively and sustainably. We will have to start living within our means again, rather than beyond them: to go forwards we need to go back to a solar economy.

Footnote

![]()

2 Weathering a Perfect Storm

‘There are dramatic problems out there, particularly with water and food, but energy also, and they are all intimately connected. You can’t think about dealing with one without considering the others. We must deal with all of these together.’

John Beddington, former chief science advisor to the UK government

In 2009, the UK Office for Science published a paper called Food, Energy, Water and the Climate: A Perfect Storm of Global Events? Written by John Beddington, then the UK government’s chief science advisor, A Perfect Storm is a harrowing document. At least it is if you take it at face value, which is exactly what the media did. In summary, the report highlights the fact that the world’s projected population growth by 2030 will lead, together with the incumbent economic and environmental factors, to a 30 per cent increase in demand for water and a 50 per cent increase in demand for food and energy. The press went to great lengths to ensure that the scale of these challenges was not understated. Good news sells few papers and in that regard A Perfect Storm made for excellent copy. Yet there’s another way of looking at the information contained in the report. Beddington’s erudite analysis of the challenges is certainly not bedtime reading for those of a nervous disposition, but the report’s real success, and one rarely noted, is that it highlights everything that we need to do: as the starting point for a strategy to address these challenges, it could not be better.

A Perfect Storm describes not the end of the world, but a starting point for its salvation. It’s definitely not the best place to start from, but the most important thing is that we do know where to start. The implications of population growth will not prove to be as easy to ignore for much longer. New inhabitants are being added at the rate of 6 million each month (the equivalent to a city the size of Rio de Janeiro). They will not be spread evenly. In the developed world outside the USA low birth rates mean that indigenous populations are in decline in many countries. By 2020, there will be more people over the age of 60 than under 20 in many European states. Conceived in the 1940s, the UK’s welfare state, which serve...