Amuthement

In Hard Times the lisping circus-owner Sleary repeats, like a parrot with Tourette’s syndrome (an epidemic condition in Dickens’s fiction), his rule of life: ‘People mutht be amuthed.’ Sleary, in terms of his narrative presence, is very much a peripheral figure, but on the subject of the human need for something other than pedagogic instruction he has full Dickensian authority.

Hard Times is what the Victorians called a ‘Social Problem Novel’, centred on the wholly unamusing Preston mill-workers’ strike of 1854. Dickens locates Preston’s social problem as originating in what Carlyle called ‘cash nexus’: the belief that the only bond between mill-owner and mill-hand was the money that passed between them. This hard-nosed hard-headedness (hard-heartedness?) Dickens associated with the Manchester school of economics – Utilitarianism.

Economists scorn Dickens’s amateurish grasp of their dismal science. But where ‘amuthement’ was concerned he was expert. Utilitarianism, he felt, was anti-life. It did to human existence what maps do to landscape. It’s exemplified in Bitzer’s disintegrated definition of a horse (he’s the prize-pupil in Thomas Gradgrind’s school).

The 1850s, when Dickens serialised Hard Times in his weekly paper, Household Words, saw an explosion in the travelling circus. They specialised in clever canines and trick equestrianism – the original horse and pony show. The big ones might even have elephants. Dickens alludes to the wondrous jumbo in his description of the great factory in Preston (‘Coketown’) ‘where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness’. How, one shudderingly wonders, would Bitzer describe that quadruped?

Hard Times opens in a schoolroom with Gradgrind laying down his educational theory: ‘Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life.’ To which Dickens responds: ‘What about Fiction?’

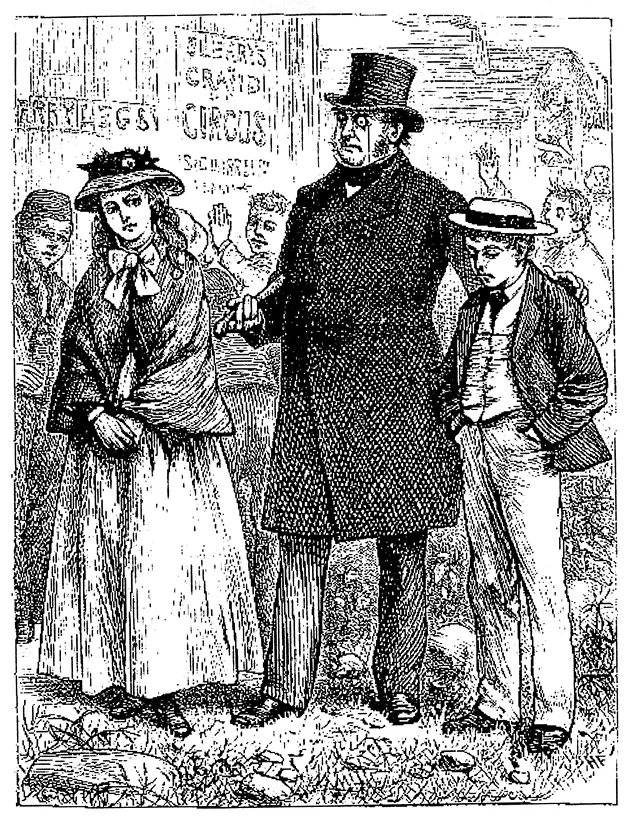

Mr Gradgrind objects sternly to the circus.

A few months before the great strike, Manchester opened the country’s first free public library. But what to put in it? The utilitarian authorities decreed Gradgrindish ‘factuality’. No, insisted Dickens. Fiction should also feature prominently on those library shelves (he, too, was a trade-unionist of kinds: just like those mill-workers). His plea was borne out by the first statistics (Manchester loved what Cissy Jupe calls ‘stutterings’). The most popular book borrowed from the library was The Arabian Nights. Dickens refers to it frequently in his novel.

Point proved by Sinbad the Sailor and Jumbo the Pachyderm. People mutht be amuthed. But it would, alas, be some years before the Manchester Public Library stocked the work of that most amusing of writers, Boz.

Architectooralooral

Every reader of Great Expectations laughs at the above malapropism. Joe Gargery, the blacksmith with muscles of iron and a heart of gold, has come up to London – his first visit, we apprehend. He calls on Pip, now well on the way to becoming an arrant snob. ‘Have you seen anything of London, yet?’ asks Pip’s housemate, Herbert. ‘Why, yes, Sir’, replies Joe,

This is not Warren’s boot-blacking factory by Hungerford Stairs where the twelve-year-old Charles was put to work while his father was in debtors’ prison, but the imposing Day and Martin establishment at 97 High Holborn. It was not the first sight a tourist on his first trip to London – even one as ingenuous as Joe Gargery – would seek out. The coded reference is clear enough. Great Expectations is an autobiographical novel and this is a sliver of raw autobiography.

Hungerford Stairs, where the young Dickens suffered.

During his lifetime Dickens told only his designated biographer, John Forster, about his blacking factory ordeal as a child. But it pleased him to slip in sly references in his fiction. In Nicholas Nickleby there is a passing reference to a ‘sickly bedridden hump-backed boy’, whose only pleasure is ‘some hyacinths blossoming in old blacking bottles’. The ‘Warren’ figures centrally in Barnaby Rudge. Most direct is the description of the Grinby and Quinion factory in his other autobiographical novel, David Copperfield:

Dickens also never forgot. Warren’s blacking is no longer available in the shops, but for those who look carefully there is a trembling black fingerprint smudging every page he wrote.

Art

Dickens lived through a revolutionary period of art in Britain and Europe. Across the Channel, Impressionism re-imagined the visible world. The American artist, Whistler, threw his paint pot in the face of the British public – and went to court against art critic John Ruskin to justify the act. Ruskin himself fathered the most revolutionary home-grown movement, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Dickens was – viewed from one angle – an artistic impresario. Ever since ousting the luckless Robert Seymour from the Pickwick Papers (and turning down a hopeful young W.M. Thackeray as not a good enough draughtsman) he instructed a series of leading artists exactly how they should illustrate the Dickens texts. All his monthly series had two full-page etchings on steel and an illustrated wrapper. His later serials featured woodcuts and new lithographic technologies.

The roll call of artists who worked for (not with) Dickens is impressive: George Cruikshank, Hablot Knight Browne, Luke Fildes, George Cattermole, Daniel Maclise, Clarkson Stanfield, Richard Doyle, Samuel Williams, Samuel Palmer.

Dickens’s initial preference was for the light-fingered cartoon/sketch, as practised by Cruikshank. In his later career he favoured ‘dark plates’ – static and realistic. Luke Fildes’s ‘veritable photographs’ (as Dickens called them) for Edwin Drood represent the endpoint of the journey from the Cruikshankery of Oliver Twist.

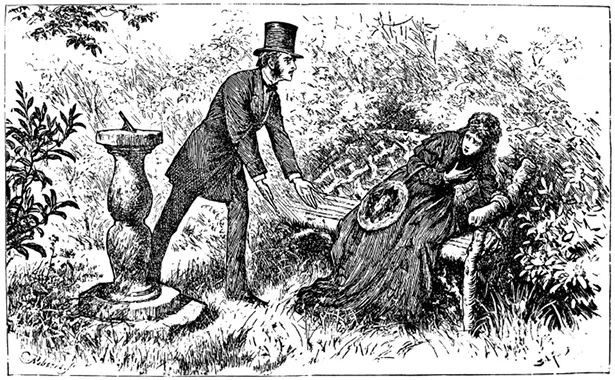

Luke Fildes, from The Mystery of Edwin Drood, 1870.

Dickens, scholars have argued, actually and literally saw the world differently at the end of his life. Photography had made a new reality.

Dickens’s dictates to his artists (none of whom were munificently paid) were underpinned by conventional taste verging on prejudice. He wrote nothing more alarmingly prejudiced, critically, than his hysterical assault on John Millais’ early Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece, ‘Christ in the House of his Parents’, as it was exhibited in the Royal Academy in summer 1850:

It’s a grotesque outbreak of Podsnappery in a man whose judgement, in virtually everything of any importance, was normally so sound. When it came to art, Dickens was that awful English thing – ‘the man who knew what he liked’.

Baby Farming

Few great writers have been less interested in tilling the soil than Dickens. There was, however, one kind of farming that excited his interest – baby farming. It seems on the face of it a Swiftian fantasy of the Modest Proposal kind. But baby-farming was big business in the early 1840s.

During the cholera epidemic of 1849 (see ‘Blue Death’) there was death everywhere in London, but on total extinction level at the Drouet Establishment for Pauper Children in Tooting. The institution had been set up in 1825, as a dump for the metropolis’ unowned offspring.

By law they had to be looked after by the London authorities until they were fourteen – when the workhouse opened its uncharitable doors to them unless, like Oliver Twist, they could be farmed out again as pseudo-apprentices (many of the girls went straight into prostitution). Education, or any preparation for life, in the farm was virtually non-existent.

There were some 1,400 inmates at Drouet’s establishment in 1849 yielding four shillings and sixpence per head, per week, from public funds. They were crammed into accommodation worse than the black hole of Calcutta. Almost 200 died of cholera, over the half the children were infected.

A first inspection whitewashed Peter Drouet, the owner. It was bad air (‘atmospheric poison’) from London that was at fault. A second inspection, as the death rate soared, was highly critical. If there was indeed ‘atmospheric poison’ it was from the luckless children’s excrement, which made the inspectors retch. There was not a single case of cholera in Tooting (then green-field countryside), outside Drouet’s pest hole.

Dickens fired off four articles in his ...