- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

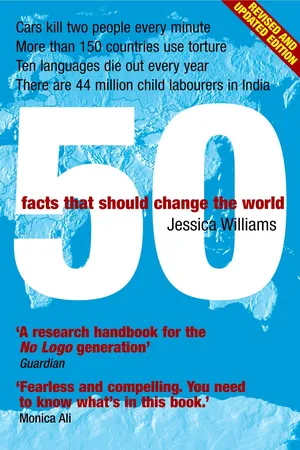

50 Facts That Should Change the World

About this book

In this new edition of her bestseller, Jessica Williams tests the temperature of our world and diagnoses a malaise with some shocking symptoms. Get the facts but also the human side of the story on the world?s hunger, poverty, material and emotional deprivation; its human rights abuses and unimaginable wealth; the unstoppable rise of consumerism, mental illness, the drugs trade, corruption, gun culture, the abuse of our environment and more. The prognosis might look bleak, yet there is hope, Williams argues, and it's down to us to act now to change things.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 50 Facts That Should Change the World by Jessica Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Globalisation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One in five of the world’s people lives on less than $1 a day

Here is the saddest fact about poverty: it really doesn’t have to be this way. For less than 1 per cent of the income of the wealthiest countries each year, the worst effects of poverty could be greatly diminished.1 People would have enough to eat, basic services like health and education would be available to all, fewer babies would die, pandemic diseases could be brought under control.

Poverty is not just a matter of a lack of material wealth – the ability to buy bread, say, or basic farming tools. Where there is poverty, people do not get access to medicine or healthcare, so their years of healthy life are diminished. Rather than staying in school or receiving training, children are sent out to work. The cycle of ill health and deprivation is hard to break. People living in poverty are vulnerable, and they are voiceless. Where there is no security of food or income, people cannot make choices. They easily fall prey to crime and violence. A young woman in Jamaica sums up her feelings: she says poverty is ‘like living in jail, living in bondage, waiting to be free’.2

In 2000, the United Nations agreed in its Millennium Development Goals to halve the number of people living in poverty by 2015. Seven years later – at the half-way point of the Goals – the UN warned that progress in many areas was too slow. Again and again since 2000, rich and poor countries had promised to work together to alleviate poverty. Richer countries agreed to pledge 0.7 per cent of their national incomes, while poorer countries agreed to implement political reforms to ensure aid money was spent wisely and accountably.3 But agreeing to make a commitment and then actually honouring it are two very different things, and it seems that rich countries are already falling behind in their commitments. Aid contributions from the countries of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (which account for at least 95 per cent of world aid disbursements) rose by 32 per cent in 2005 but amounted to just 0.33 per cent of gross national income4 – well below the UN’s suggested 0.7 per cent. The UN is warning that although some countries are on target to reach the Millennium goal on poverty, many others will not. Overall, the targets should be met – but if we take two large countries out of the equation, India and China, they will not be. Why are some countries succeeding and others failing – and what can we do about it?

In the 1990s, the proportion of the world’s population living in extreme poverty – defined as living on an income of below $1 a day, adjusted for relative purchasing power – fell slightly, from 30 per cent to 23 per cent.5 In China, more than 150 million people have moved out of poverty in the past decade.6

But in 54 developing countries, income fell during the 1990s. Twenty of these were in sub-Saharan Africa, and seventeen were in Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). In Eastern Europe, the fallout from the collapse of communism has led to spiralling unemployment and rapid economic decline. In Africa, development has been hit hard by falls in life expectancy caused by the HIV/Aids pandemic, and small landlocked countries have been hit hardest of all. At current growth rates, it will take until nearly 2150 for sub-Saharan Africa to halve the number of people living in poverty.7 Some countries are getting richer, yes; but many are getting poorer.

Across the world’s population, the divide between rich and poor is growing ever wider. We think of countries like Brazil showing grotesque levels of inequality between wealthy industrialists and the urban poor living in shanty towns, but distribution of wealth across the world’s people is even more unequal than that.8 In 1960, the percapita gross domestic product (GDP) of the richest twenty countries was eighteen times that of the poorest twenty. In 1995, this gap had yawned to 37 times.9 Today, the world’s richest 1 per cent receive as much income as the poorest 57 per cent.10

Even in countries where poverty levels are declining, there are inequalities which mean not everyone is benefiting from those advances. China’s development strategy directs funding towards industry and away from agriculture, so people in the richer coastal regions profit at the expense of the rural poor. In Mexico, the poorest states in the south are far from the US border and so opportunities for trading and employment are few; the richest 10 per cent of the population earn 35 times more than the poorest 10 per cent.11 A high degree of inequality in a society leads to a vicious circle: people have less incentive to work hard because advancement in society is very difficult, and this leads to rising crime, social unrest and corruption – which in turn threatens economic stability.12

If we cannot succeed in meeting the Millennium Development Goal on poverty, the industrialised world will have failed. We will have failed not only the people that we promised to help, but in some way we will have failed ourselves. Listening to our leaders trumpet the benefits of globalisation and worldwide free trade, we believed that we were doing something to help. We must make sure that our governments and our multinational companies prove us right.

First of all, we need to think about reducing poverty as an imperative. When governments look to cut public spending, overseas development aid is often among the first areas to be trimmed – but it shouldn’t be. As economist Jeffrey Sachs and director of the UN Human Development Report Sakiko Fukuda-Parr wrote, ‘the question is not whether the rich countries can afford to do more or have to choose between, say, defense and reducing world poverty. Since less than 1 per cent of national income is needed, the question is only whether they will make the elimination of the world’s extreme poverty a priority.’13

Development aid should, for example, be put at a far higher priority than the wasteful and unfair system of agricultural subsidies paid out by the US and Europe. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries spend around $300 billion a year in supporting their farming sector – more than five times what they spend on development aid.14 This lavish aid encourages farmers to produce far more crops than they need to, and surpluses are then dumped on the developing world.

If rich countries decided to end agricultural subsidies and remove barriers to imports from the developing world, the results could be dramatic. For every dollar that developing countries receive in aid, they lose two dollars because of unfair trade barriers.15 Market liberalisation needs to go both ways, so that developing countries don’t open their doors only to be faced with stiff rich-world trade rules.

But merely dropping trade barriers won’t solve the problem. Reducing the crippling debt burdens faced by many developing countries is a crucial part of any poverty-reduction strategy: once they are freed from the need to spend all their resources in servicing enormous loans, governments are able to spend more on vital infrastructure, health and education. G7 leaders committed to cancelling $100 billion worth of debts owed by the 42 poor countries that were identified by the World Bank and the IMF as ‘highly indebted poor countries’ (HIPC); at the time of writing 20 countries had completed the HIPC initiative but aid agencies argue that the structural and economic reforms required to complete the process leave countries more vulnerable, not less. In July 2005, the G8 nations agreed to forgive the debts of all completion-point HIPCs (and potentially many other countries still involved in the process). But aid agencies still called on the G8 to ensure that the debt forgiveness was ‘new money’ – so HIPC countries didn’t then miss out on other forms of aid.16

It is clear that in order to put in place important development infrastructure – like schools, hospitals, water and sanitation systems – large injections of donor finance will be needed. But this should be in the form of grants, not loans, as the last thing many of these countries need is to take on yet more debt. It also needs to be effective aid, given to the right people at the right time, and with a sense of the distortions that massive injections of money can cause to a society and its people.

The UN Human Development Report summarises good practices for donors and recipients. On the part of donors, aid should encourage decentralised decision making (by local communities rather than central governments), co-ordination of projects and programmes to align with the country’s needs, and accountability. Aid should also not be tied to specific conditions. On the recipient’s side, there should be institutional reform to promote transparency and good governance, more widespread participation in development issues and an increased level of oversight (by non-governmental organisations, civil society and individuals) to increase accountability.17 Simply put, donors can do much to make sure the money goes where it’s needed, and recipients can make sure it gets spent on the right things by giving people in communities a voice.

Developed nations also need to be prepared to share technology to help poorer countries. This doesn’t mean just computer and communications technology, though that is important, but also making patent laws accessible to innovators in developing countries, committing to researching and developing drugs to combat illnesses that are endemic in the developing world, and helping to provide clean energy alternatives to reduce pollution and lower fuel costs. Providing training to help people get the most out of their land may be the most valuable donation of all: for example, the Heifer charity helps families by donating livestock and training to small farmers and communities. Once the farm is back on its feet, the recipients then ‘pass on the gift’ by donating their animal’s offspring to another needy family.18

Above all, we need to make sure that the forces of globalisation do not work merely to make rich countries richer. The benefits need to flow both ways. Developing nations made their voices heard loud and clear at the World Trade Organisation talks in Cancun, and put the issue of poverty and trade at the top of the world’s agenda. Now it is up to the developed world to rise to the challenge.

On the eve of the Cancun talks, Britain’s then chancellor Gordon Brown wrote that afterwards, ‘globalisation will be seen by millions as either a route to social justices on a global scale, or a rich man’s camp’.19 The developed world doesn’t have much time to change the course of globalisation, but then it’s not that hard to do what’s required. Living up to our promises, giving people a voice, playing fair – none of these things seems unreasonable. In fact, they seem like the very least we should be doing.

More than 12,000 women are killed each year in Russia as a result of domestic violence

‘He beat me so hard that I lost my teeth. The beatings happened at least one time each month. He used his fists to beat me. He beat me most severely when I was pregnant … the first time he beat me, and I lost the baby. I was in the hospital. The second time was only a few days before a baby was born, and my face was covered in bruises. He beat me and I went to my parents. My father refused to take me to a doctor. He said, “what will I say, her husband beats her?”’1

No one should have to live in fear of violence. And no one should have to live in fear of the people who are supposed to love them. Yet every year, around the world, millions of women are victims of assault by their boyfriends or husbands.

In many countries, it’s a dirty secret, something that happens between man and wife, an area where the law cannot and should not intervene. Of all the violent crime in society, it’s probably the least visible – which makes it the hardest to tackle. But the consequences of inaction are tragic.

One estimate says that 3 million women are physically abused by their husband or boyfriend each year2 – another that one in three women will be beaten, coerced into sex or otherwise abused during her lifetime.3 In Russia, it’s estimated that between 12,000 and 14,000 women are killed each year by their husbands – that’s one every 43 minutes. Contrast this with America, where 1,247 women were killed by an intimate partner in 2000, and the enormity of the problem becomes clear. Russian NGOs say that unless serious injury or death results, abuse is seldom reported, so it’s nearly impossible to guess how many women are abused each year.

Russian women’s groups have been trying to raise awareness of this silent crisis – trying to get women to speak out about abuse, and pressuring the government to provide facilities for dealing with women who’ve been victims of violence. But they acknowledge they are dealing with some very deeply entrenched attitudes. One Russian proverb holds that ‘if a man beats you, that means he loves you’. Getting women – and indeed men – to believe otherwise is the first challenge.

One of the few Russian doctors allowed to conduct medical examinations to provide evidence of violence points to Russia’s violent history as one reason for these attitudes. According to Yury Pigolkin, ‘our society is extremely aggressive, going from one war to another. This creates a kind of citizen to whom the principles of conduct generally acknowledged in the US are not applicable. Programs made for Americans are powerless here. This is mainly due to economic factors: when a person is poor, when he’s destitute, when he’s barely surviving and not able to pay his rent, it’s [hardly effective] to impose a fine on him.’4

It seems that the massive economic and social upheaval in the post-Soviet era has left men demoralised, needing to control. Many insist their wives give up work, leaving the women totally dependent on their husbands. If things turn bad, they are powerless to leave. Housing shortages mean that couples who have divorced are often forced to continue living together. With support from the authorities grudging at best, NGOs aren’t optimistic about change. In 2001 there were only six women’s shelters in the whole of Russia, with none in Moscow. When one NGO representative asked an Interior Ministry representative to set up a special team to treat and examine victims of domestic and sexua...

Table of contents

- Praise for 50 Facts that Should Change the World

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Introduction: Why should these 50 facts change the world?

- The average Japanese woman can expect to live to be 84. The average Botswanan will reach just 39

- A third of the world’s obese people live in the developing world

- If you stand at the junction of Oxford Street and Regent Street in central London, there are 161 branches of Starbucks within a five-mile radius

- China has 44 million missing women

- Brazil has more Avon ladies than members of its armed services

- Ninety-four per cent of the world’s executions in 2005 took place in just four countries: China, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the USA

- British supermarkets know more about their customers than the British government does

- Every cow in the European Union is subsidised by $2.50 a day. That’s more than what 75 per cent of Africans have to live on

- In more than 70 countries, same-sex relationships are illegal. In nine countries, the penalty is death

- One in five of the world’s people lives on less than $1 a day

- More than 12,000 women are killed each year in Russia as a result of domestic violence

- In 2006, 16 million Americans had some form of plastic surgery

- Landmines kill or maim at least one person every hour

- There are 44 million child labourers in India

- People in industrialised countries eat between six and seven kilograms of food additives every year

- David Beckham’s deal with the LA Galaxy football team will earn him £50 every minute

- Seven million American women and 1 million American men suffer from an eating disorder

- Nearly half of British fifteen year olds have tried illegal drugs and nearly a quarter are regular cigarette smokers

- One million people become new mobile phone subscribers every day. Some 85 per cent of them live in emerging markets

- Cars kill two people every minute

- Since 1977, there have been more than 120,000 acts of violence and disruption at abortion clinics in North America

- Global warming already kills 150,000 people every year

- In Kenya, bribery payments make up a third of the average household budget

- The world’s trade in illegal drugs is estimated to be worth around $400 billion – about the same as the world’s legal pharmaceutical industry

- A third of Americans believe aliens have landed on Earth

- More than 150 countries use torture

- Every day, one in five of the world’s population – some 800 million people – go hungry

- Black men born in the US today stand a one in three chance of going to jail

- A third of the world’s population is at war

- The world’s oil reserves could be exhausted by 2040

- Eighty-two per cent of the world’s smokers live in developing countries

- Britons buy 3 billion items of clothing every year – an average of 50 pieces each. Most of it ends up being thrown away

- A quarter of the world’s armed conflicts of recent years have involved a struggle for natural resources

- Some 30 million people in Africa are HIV-positive

- Ten languages die out every year

- More people die each year from suicide than in all the world’s armed conflicts

- Every week, an average of 54 children are expelled from American schools for bringing a gun to class

- There are at least 300,000 prisoners of conscience in the world

- Two million girls and women are subjected to female genital mutilation each year

- There are 300,000 child soldiers fighting in conflicts around the world

- Nearly 26 million people voted in the 2001 British General Election. More than 32 million votes were cast in the first season of Pop Idol

- One in six English teenagers believe that reality television will make them famous

- In 2005, the US spent $554 billion on its military. This is 29 times the combined military spending of the six ‘rogue states’

- There are 27 million slaves in the world today

- Americans discard 2.5 million plastic bottles every hour. That’s enough bottles to reach all the way to the moon every three weeks

- The average urban Briton is caught on camera up to 300 times a day

- Some 120,000 women and girls are trafficked into Western Europe every year

- A kiwi fruit flown from New Zealand to Britain emits five times its own weight in greenhouse gases

- The US owes the United Nations more than $1 billion in unpaid dues

- Children living in poverty are three times more likely to suffer a mental illness than children from wealthy families

- Sources for the 50 Facts

- Notes

- Glossary

- Getting involved

- INDEX