![]()

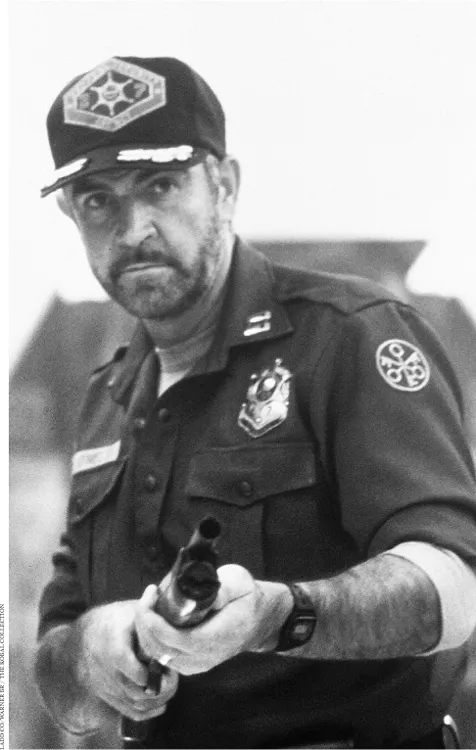

50. OUTLAND (1981)

What makes a western, a western? Is it just a collection of the right sort of landscapes, of flat-topped mesas, the Great Plains or the Black Hills of South Dakota, the backdrops one expects to see? Just stick a few buffalo in front of the lens, or the dusty streets of a frontier town, or a wagon train or a shootout, set it somewhere west of the Mississippi anytime between 1780 and 1900 before the arrival of electricity and motor cars, and there you have it? Or are westerns harder to pin down? Perhaps there’s more to the genre than what critics have always said are its Achilles heels: too one-dimensional, too predictable, too few locations, not enough variety. What if whether a movie is a western or not depended on more intangible things, like how it feels to be alone and outnumbered, what it’s like to be a long way from home in an alien land, or having to wear a gun everywhere you go and living by your wits in an environment that can kill you, but which isn’t nearly as dangerous as your ultimate enemy: man? Even in the wild west, man was still the ultimate predator. Maybe what is true on the Great Plains can be just as true on the moons of Jupiter.

I recently watched Outland again after not seeing it for maybe twenty years, and it looked every bit as gritty and taut, tense and plausible as it did before. Sean Connery is Marshal William O’Niel, a Federal District Marshal who has been sent to investigate a titanium mining colony on the Jovian moon of Io, where the miners have been dying in a rather gruesome series of apparent acts of suicide by exposing themselves to the moon’s zero atmosphere, resulting in the explosive decompression of their bodies. O’Niel discovers that the colony’s high rate of productivity is the result of an illegal supply of deadly narcotics that allow the miners to work for days at a time until they eventually burn themselves out and become psychotic. The colony’s administrator, Mark Sheppard (Peter Boyle), is determined to maintain the corrupt and highly profitable status quo and hires two assassins to come on the next supply shuttle to kill O’Niel, who becomes aware of what is coming and prepares himself for the confrontation. Digital clocks throughout the colony continually count down to the arrival of the shuttle. O’Niel is ostracised and very much on his own, always having to watch his back. The tension builds relentlessly, helped along by the ominous, almost hypnotic counting down of those digital clocks, until the shuttle’s arrival heralds the final showdown.

Peter Hyams, the American director, cinematographer and screenwriter, was interested in making a western movie set in a science fiction context, and refused to believe the early 1980s misplaced conception that the western was dead. He triumphantly transfers the motifs and characters of countless 19th-century frontier towns to Io, and not only that but took the opportunity to add a nice corollary on corporate greed as well. The result? Outland becomes a thoughtful futuristic homage to – and adaptation of – the great 1952 classic High Noon, in which Gary Cooper plays a marshal abandoned by the very people he has sworn to defend, waiting for the arrival of a train carrying his own would-be assassins.

O’Niel’s only ally is the company doctor, Dr Lazarus (Frances Sternhagen), who somehow remains sufficiently detached from the corruption swirling about her and assists O’Niel in unravelling the complicity of the mining company – Conglomerates Amalgamated – and then going further, helping O’Niel to dispatch the first of the hired assassins. The second is also killed, as is the corrupt Sgt. Ballard (Clarke Peters), O’Niel’s own deputy, before a final confrontation with Sheppard whom O’Niel knocks out and whose ultimate fate – either killed at the hands of his own accomplices or brought to trial – can be left to the discretion of the viewer. O’Niel then boards the next shuttle back home to his family, and a very frontier-like brand of justice again wins the day.

Outland was the first film to use Introvision, a twist on traditional front projection techniques that allowed actors to be placed between plate images, to in effect walk inside a two-dimensional background image. Introvision remained popular until the era of digital compositing in the mid-1990s. The enduring images of this timeless film for me, however, remain the shotgun O’Niel chose to use in his defence – a very deliberate ‘relic’ and a nod to the Remingtons and Winchesters that helped subjugate the old west. And of course there was the wonderful sound of that digital clock, relentlessly ticking, ticking, ticking, counting down the seconds in a claustrophobic-looking future full of shadows and steam and steel grates reminiscent of Ridley Scott’s masterpiece Alien, which had been released two years earlier.

Unlike Alien, though, which frightened us out of our seats with acid-filled monsters, Outland’s message is far more chilling. It reminds us that technology, the future and the colonising of space will not by default mean that we will be triumphing over our inner demons. It reminds us that though Io may be far removed from the Great Plains and the Black Hills and the Colorado Plateau, from Tombstone and Dodge City and High Noon’s Hadleyville, the western is not about a certain time, a particular place or a costumed look. It is far more sinister than that. The west is everywhere that mankind goes to that is new and untamed, every place where the law is absent and greed simmers. It reminds us that even in the dark, cold reaches of outer space, the ultimate enemy will still be man.

49. WESTWORLD (1973)

Yul Brynner echoes his ‘Man in Black’ character of Chris from The Magnificent Seven as an android known only as ‘The Gunslinger’ in this endearing sci-fi/western thriller, written and directed by Michael Crichton and based on his own best-selling book. The plot centres on a futuristic resort for adults called Delos, which consists of three themed worlds: the debauchery of Roman World, the fantasy of Medieval World and the lawlessness of West World. Drawing his inspiration from Disneyland, Crichton’s high-tech park is populated by purpose-built androids all controlled and maintained by a hidden throng of technicians, androids that exist purely for the pleasure and amusement of the park’s guests. Naturally, not long after the arrival of the film’s two central characters, played by Richard Benjamin and James Brolin, who are happy to pay the resort fee of $1,000 a day to have the adventure of a lifetime, things begin to go horribly wrong as androids begin turning on guests, hunting them down and killing them in a frenzy of wanton violence.

Westworld is unashamedly cliché-ridden, with almost every scene done a thousand times before in the genre. But that mattered little to this impressionable teenager and movie-goers everywhere who, for the very first time in motion pictures, became privy to an electronic, pixelated view of the world as seen through the eyes of The Gunslinger – the sort of voyeuristic glimpses audiences have since become so accustomed to seeing through the eyes of Schwarzenegger’s Terminator. Crichton wanted to go a step beyond the wide-angled lens approach used to such good effect in 2001: A Space Odyssey when Stanley Kubrick showed audiences the elongated world as the computer HAL saw it. In Westworld, using digital image processing, Crichton crafted a visual masterstroke that seared those pixelated images deep into the audience’s psyche.

And it almost didn’t happen. Crichton badly wanted this never-before-seen effect, but because of the studio’s miniscule budget ($1.25 million) he couldn’t afford the $200,000 that NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory wanted for doing it (nor could he wait out their projected timeframe of six months). So he turned instead to a budding computer graphics artist, John Whitney Jr, the son of John Whitney Snr the great animator and analogue guru, who gave him the look he wanted for a tenth of the cost. Westworld went on to win a number of prestigious science fiction and fantasy awards for its special effects.

Almost all its scenes were shot using standard lenses, though its budget was stretched to breaking point by Crichton’s insistence on using rear and front projection, as well as blue screen – special-effects techniques usually reserved for directors with more generous allowances. The budget was so small in fact that the art director, Herman Blumenthal, had a paltry $70,000 for set construction, forcing him to re-use sets on different locations and hoping no one would notice. Even Yul Brynner, who was experiencing lean times himself, agreed to do the film for a modest $75,000. And there were the usual on-set mishaps. Brynner was hit in the eye from the wadding off a blank cartridge and had his cornea scratched. Brolin was bitten by a rattlesnake while preparing for a scene when the fangs from its lower jaw penetrated the arm protector he was wearing under his shirt sleeve.

Crichton would revisit his idea of an amusement park running amok years later in Jurassic Park. But it wasn’t the robotics that thrilled me as much as seeing Brynner parody his character from The Magnificent Seven, my favourite film of my childhood. One day on the set Brynner, who was teaching Richard Benjamin how to shoot a gun, gave up one of the secrets as to what makes a believable gunman when he said: ‘You look at the biggest western stars, and I’ll show you that they blink when the gun goes off’.

When the finished film was shown to studio executives nobody liked it, but the preview audiences came back with an astonishing 95 per cent approval, one of the highest in the studio’s history. It is not without its flaws, but Westworld is an example of how a fresh idea, worked on by a cast and crew who cared about what they were doing, could deliver a film that is neither profound nor silly. And it proves that the clever use of technology combined with a seemingly unstoppable bad guy can produce a film that is immune to becoming dated when set in that most mythic era of time and space, the American west.

48. THE IRON HORSE (1924)

No single event did more to tame the wild west than the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, a 3,069 km/1,907 mile railway line that took the existing eastern rail network westward from Council Bluffs in Iowa to San Francisco Bay on the Pacific coast. Three independent railroad companies combined to complete it, and the famous ‘Last Spike’ was driven in on Promontory Summit, Utah, on 10 May 1869. At long last the vision of Dr Hartwell Carver, the ‘father of the Pacific Railroad’, whose 1832 article in the New York Courier and Enquirer would be the first of his many petitions to Congress to find the funds to build it, had been realised.

Forty-five years after the hammering in of that final spike, a young John Ford came to Hollywood and found work as a stunt double before being given his first directorial debut in 1917 with The Trail of Hate, the first of many two-reelers. The idea of the ‘epic’ western had arrived in 1923 with Paramount’s The Covered Wagon, which single-handedly revived the public’s waning interest in the genre and proved so popular with audiences that Ford, by now working for the Fox Film Corporation (later 20th Century Fox) and a veteran director of more than 50 films, was given what became the most significant western of his silent period – the story of the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad, The Iron Horse. The man who, more than any other director in Hollywood, would laud and glorify the freedom and expansiveness of the frontier, was recreating the one event that did more than any other to bring it to a close.

The film’s 300-plus cast and crew were housed in twenty rented Pullman railroad sleeper cars or slept in the clapboard interiors of the town sets they’d built, and filming took place on the barren desert flats around the town of Wadsworth, Nevada, in the bitter winter of 1924 when snowfalls would routinely cover the sets. The film, which began without a script and with little more than a synopsis, sets its story against the relentlessly encroaching Central Pacific Railroad and Union Pacific Railroad companies as they close in on Promontory Summit. It recounts the life of Davy Brandon (played as an adult by George O’Brien, a former stuntman and camera assistant), who as a child witnesses the death of his father, a surveyor who dreamt of building a railway to the west, at the hands of a half-breed Cheyenne (Davy’s back-lit frame as he stands over his father’s dead body also gives the film its only real expressionistic, noir moment). Fast forward to 1862 and Davy, now a strapping scout and frontiersman, has his own dream – to see the completion of his father’s ambition after the bill authorising its construction is finally signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln.

Many later ‘Fordian’ trademarks are already evident, including the pastoral nature of the landscape, the sense of ‘Manifest Destiny’ that drove pioneers ever-westward, the presence of the labourer and the immigrant on whose backs the west was built, and the innocence of the land when seen through the eyes of children. Ford also wanted the film to look as historically accurate as possible, managing to gather together 10,000 head of cattle and over 1,300 buffalo, as well as studying photographs of the actual ‘Last Spike’ ceremony in order to recreate it on film. The movie also had at its disposal two very impressive ‘Iron Horses’ of its own – two steam locomotives that some said were the very same that met nose to nose at Promontory Summit on that historic day. As nice a touch as that would have been, unfortunately they were not. The two engines, the ‘Jupiter’ and the ‘UP 116’, had long since been scrapped.

Ford had a personal connection with the railway. A family relative, Michael Connolly, sponsored his own father’s migration from Ireland and was a construction worker on the Union Pacific line, a fact that may have contributed to Ford’s tendency in the film to side with the workers in their struggle with the unfettered capitalism of the railroad companies and his sympathetic depiction of the various immigrant groups (Irish, Chinese, Italian and African-Americans) who together forged some unlikely communities.

The fact the film had a fairly typical B-movie storyline was forgotten in the wake of its scale and staggering success. The Iron Horse made more than $2 million in America and became the year’s top-grossing movie. The film’s sweeping cinematography, particularly in its images of Indians racing across the landscape on horseback, combined with great stunt work, richly orchestrated crowd scenes and a realism born of its epic scale, showed here was a director who was clearly in a period of personal transition, from a mere deliverer of two-reeled ‘pulp’ to a man becoming adept at communicating his own vision of the west – a vision that would determine how the frontier would be imagined by movie-goers for generations to come.

47. TRUE GRIT (1969)

Both film versions of Charles Portis’ novel of how a fourteen-year-old girl from Arkansas, Mattie Ross, hired tough US Marshal Rooster J. Cogburn to help her hunt down and bring to justice her father’s killer, Tom Chaney, have found their way into my list; the 2010 adaptation by the writer/director team of Joel and Ethan Coen, and the original 1969 version with Kim Darby as Mattie, John Wayne as Rooster, and singer Glen Campbell as the Texas Ranger La Boeuf. Never claiming to be an accurate rendering of Portis’ classic tale, considered by many to be one of the finest American novels ever written, John Wayne nevertheless considered the screenplay by Marguerite Roberts the best he’d ever read.

One of the doyennes of screenwriting in the 1930s, Roberts – blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951 and unable to work in Hollywood for nine years – found favour once again with the big studios in the 1960s. Writing the screenplay, however, Roberts felt that the ending, in which Mattie loses her arm after a snake bite and then 25 years later visits Cogburn’s grave, just too depressing. So she had Mattie and Cogburn instead visit her family plot, with Mattie offering a spot to Cogburn, and he agreeing – as long as it wasn’t to be used too soon! In Roberts’ version, Mattie, who was the central character in the book, almost takes a back seat to Wayne’s overwhelming presence. Some might well say that the film appears a little ‘flat’ and in need of rescuing until John Wayne makes his appearance, and the film does lack many of the humorous asides the Coen brothers did so well, particularly in relation to La Boeuf’s pride in being a Texas Ranger.

There are some notable discrepancies, too, between the novel and the 1969 film. Unlike the book (and the Coen brothers’ version), the film played down the many biblical references and overtones, which were not only a nice touch but ...