![]()

EUROPE

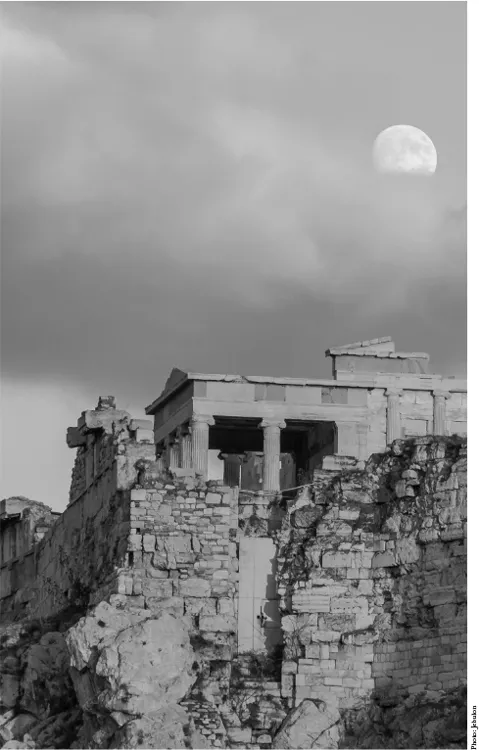

THE ACROPOLIS, ATHENS

The Acropolis of Athens is the most important monument of ancient Greek civilisation. Looking over the city, from high on the sacred rock of Athens, this complex of ruined temples, statues and sanctuaries represents the pinnacle of Greek antiquity’s culture and achievements. It is testimony to the ancient Greeks’ advances in philosophy, politics, science and art and a symbol of the debts that our society still owes them today. The Acropolis of Athens is, arguably, the definitive monument of the Western world.

It has had many lives. Rising 490 feet above the city, the seven-acre site had superb natural defences and was used as a fortress as early as the 13th century BC. But by the 5th century BC it was beginning to take on a larger significance. Empowered, and enriched, by their recent revenge on the Persians for the sacking of Athens in 480 BC, the city began a lavish rebuilding programme. The people wanted the new Acropolis to be a symbol of Athens. This was the centre of the Greek empire: the great rays of their influence radiated from this spot. The Acropolis was to be their shining example to the world. The site is composed of many buildings: the Erechtheion, the Propylaea and the Temple of Athena Nike. But the Parthenon is, undoubtedly, the most spectacular.

Under the direction of the great statesman Pericles, the first stone was laid on 28 July 447 BC. No expense was spared. The finest architects, sculptors and artisans were hired – including Phidias, considered the greatest artist of his day, who created the statue of Zeus at Olympia, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. But although the Parthenon is seen today as the epitome of Greek architecture, it was unlike anything that had come before it.

For starters, it was the first Greek temple to be built entirely of marble – 22,000 tonnes of it were hauled up on sledges and pulleys from quarries more than ten miles away. It was also the largest temple of its kind ever built, featuring an expanded base of eight 34-foot-high columns in front and seventeen on the side. This allowed an unprecedented amount of sculptural detail. Huge rectangular panels, called metopes, covered every inch of the façade, depicting battles of gods and Greek victories over their enemies. The two triangular pediments were filled with more than twenty larger-than-life marble figures. An enormous 525-foot sculpted frieze, portraying scenes of civic celebration – an expression of Athens’ burgeoning democracy – circled the entirety of the temple’s inner sanctum. And in the heart of it, most impressive of all, stood a 40-foot tall gold and ivory statue of Athena – patron goddess of the city and the Parthenon alike.

But even more remarkable was the way it was built. There are almost no straight lines in the entire building. The base, and entablature above the columns, bend towards the middle; the steps curve upwards; the metopes tilt outward; each column bulges as if pressed down by the weight above. These subtle refinements, masterfully combined in proportion with one another, impart a sense of dynamism and vitality – as if the Parthenon is a living mass, flexing and straining under its great importance. How they built such a complicated work in less than fifteen years is a wonder in itself.

But its grandeur did not last long. Less than a decade after construction had finished, war broke out with Sparta and Greece suffered a humiliating defeat and a devastating plague. The Acropolis would remain standing for centuries, but its glory would never be the same. And then, in the early 19th century, another tragedy struck. Thomas Bruce, the Earl of Elgin – a Scottish aristocrat who was British ambassador to the Ottoman court – removed large parts of the frieze, most of the pediment statues and a number of the metopes in order to sell them to the British Museum, where they are still on display today. Whether he is viewed as a saviour (in his day locals would use parts of the Acropolis for building their own homes) or a criminal, and whether these works should be returned to Greece, is still a matter of bitter contention.

What is certain is that the Acropolis of Athens, and in particular the Parthenon, is the greatest standing testament to one of the most enlightened societies that ever lived. The ancient Greeks designed the concept of democracy. They built the foundation of Western philosophic thought and gave birth to some of the greatest, and still influential, thinkers the world has ever seen: Plato, Socrates, Aristotle. They brought us the origins of theatre and created the Olympic Games. They advanced art, mathematics and medicine. The world we live in today would be unrecognisable without the contribution of the ancient Greeks.

That’s what makes the Acropolis of Athens special. All these strands come together here in one masterful creation. Pericles boasted: ‘We shall be the marvel of the present day and of ages yet to come’. And he was right. The Acropolis is more than just a monument – it’s the birthplace of all we hold dear and a reminder of the possibilities that we may still yet achieve.

WHERE: Athens, Greece.

HOW TO SEE IT: Open 8am to 8pm daily. Take the metro to the Acropolis station and walk up from there.

http://odysseus.culture.gr/index_en.html

TOP TIPS: Go late in the day. From 5pm the coach and cruise tours have all left, meaning you’ll have the site, and sunset, all to yourself. The summer is very hot, try to avoid this time of year if possible. The Acropolis Museum nearby has excellent exhibitions of the Parthenon sculptures and more than 3,000 other artefacts from the region.

www.theacropolismuseum.gr/en

TRY THIS INSTEAD: The ancient Oracle of Delphi, at the foot of Mount Parnassos two hours west of Athens, is one of the most spectacular monuments in the entire country. Combine this with your trip to the Acropolis.

http://odysseus.culture.gr/index_en.html

STONEHENGE, ENGLAND

Stonehenge is one of the most important prehistoric monuments in the world. Built over the course of 1,500 years this 108-foot ring of concentric standing stones is one of the oldest man-made structures in the world. And yet, despite its antiquity, the sophistication of its architecture, and the challenges presented by its construction, are so enormous that its very existence has baffled people for centuries. How it was built, by whom and why is still shrouded in mystery. But recently some answers have started to emerge.

Stonehenge has been a sacred site for millennia. Located on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, the earliest archaeological records date back at least 10,000 years. At this time much of southern England was covered in woodland, but these chalky plains would have remained open, giving the site, it is thought, a special significance. Construction on Stonehenge itself began about 5,000 years ago and was eventually completed in three stages, by three separate groups of people.

First, around 3000 BC, a large earthwork barrow, or mound, was dug from the ground using tools made from antlers and then made into an inner and outer bank. Circling this 320-foot ring are the Aubrey Holes, 56 round pits about one metre across, which once contained timber posts or stones thought to be for burial and religious purposes.

The second, and most dramatic, stage of construction began in 2500 BC. Bluestones, which form the central ring of the henge and weigh roughly four tonnes each, were brought in from the Preseli Hills in Pembroke, South-west Wales, some 160 miles away. At that time, work on Stonehenge Avenue, a two-mile earthwork monument connecting the River Avon to the north-east entrance of the henge, also began. Five hundred years later, in 2000 BC, the giant sarsen stones, which form the outer ring and the inner horseshoe-shaped trilithons, each one 30 feet tall and weighing as much as 30 tonnes, were transported from the Marlborough Downs, twenty miles to the north.

For many years it was thought impossible that a Stone Age people would have the engineering knowledge and tools to erect these enormous monoliths. But modern engineering simulations have presented a solution. Once on site, it is thought, holes were dug in the ground and one end of the stone was hauled over them, with great levers placed underneath, until gravity tipped it inside. Now, resting at 30°, a system of stone counterweights and teams of men, using plant-fibre ropes, would pull it vertical and the hole would then be filled to keep it in place. Finally, an earth ramp was piled up against the upright stones and the horizontal lintels were dragged into place. They were then fastened together vertically, using carved mortice and tenon joints, and horizontally, by tongue and groove joints. The complexity of these techniques, and the intricate shaping of stones that was required, has never been seen in any other prehistoric monuments from this time.

The final stage began in the heart of the Bronze Age, around 1500 BC, when the highly advanced Wessex people arrived and carved elaborate drawings of axe-heads and daggers into the stones and finalised their arrangement into what we see today. It is estimated that in total something in the region of 30 million man-hours went into the construction of Stonehenge, making it one of the greatest collaborative undertakings in human history.

But how did they get the stones there in the first place? It’s a question that has perplexed scholars for centuries. Without the wheel, or sophisticated tools, roughly 80 Pembroke bluestones, each one as heavy as an African elephant, had to be hauled for dozens of miles across rough and uneven ground. Legend has it that Merlin, under orders from King Arthur, used his magic to shrink the stones, which had originally been carried from Africa on the backs of giants, so that they could be transported to their present site. Other theories propose the movement of glaciers or even a race of ancient aliens as possible solutions – such is the enormity of the undertaking. The truth is less fantastical, but perhaps more remarkable for it.

Modern theories speculate that the smaller bluestones were most likely dragged on sledges and rollers to the headwaters of Milford Haven in Wales, loaded up on boats and sailed along the coast and up the River Avon to Somerset. Once there, they were unloaded and hauled again into their present position. The colossal weight of the giant sarsen stones from Wiltshire presented an even more complex problem. It would have taken 500 men to haul a single stone, and many more to get them up the steepest part of the route, at Redhorn Hill.

The question is why? What we know for sure is that the stones align perfectly with the midsummer sunrise and the midwinter sunset, suggesting they may have been used for astronomical purposes. At this time, great ceremonies would have been held too. Recent laser-scanning of the stones has shown that the outer edge of the north-east sarsens, which face the earthwork Avenue, were finely dressed and scraped clean, suggesting that this was the traditional processional entrance. At the time of solstice these carefully prepared stones would have glistened like stars in the sunlight.

It was also likely used as a sacred burial site of sorts. Funeral evidence has been found here that has been dated back thousands of years, to a time before even the stones were brought here. But there are fun theories about why Stonehenge was created too, including a druid temple, a stone-age calculator, a coronation site for Danish kings and a centre for healing. Whatever you believe, what is certain is that these stones have power. Their significance is palpable. To stand beside them is to stand in the footsteps of 5,000 years of worship, wonder and awe.

But as spectacular as it is, Stonehenge is only a small part of a much larger ancient landscape. There are more than 350 burial mounds and prehistoric monuments within the ten-square-mile World Heritage Site that surrounds it, including the Cursus, Woodhenge and Durrington Wall. Twenty-five miles north is the Avebury complex, the largest stone circle in the world, at nearly 1,500 feet across, and arguably the most impressive earthwork complex in Europe. Together these sites contain a vast source of knowledge about the ancient people of Great Britain and Europe, and are one of the most treasured archaeological sites in the world. But the magic of Stonehenge isn’t about what it tells us. It’s about how it feels. This ring of stones is a testament to the power of human will and collaboration. Walk beside them, watch the sunrise over them, look up at the stars and wonder who else may have once shared this view, and why.

WHERE: Near Amesbury, Wiltshire, England (just off the A303 road).

HOW TO SEE IT: English Heritage look after the property. It’s open daily from 9.30am to 7pm, and there’s a good visitor centre nearby with multiple exhibitions about the history of Stonehenge and the surrounding area.

www.english-heritage.org.uk

TOP TIP: Summer solstice is a huge party, with tens of thousands of visitors arriving to see the sunrise and sunset. If that’s not your thing, come for the winter solstice instead. It’s still possible to see the alignment of the stones, but with far fewer visitors.

TRY THIS INSTEAD: Avebury is an equally impressive prehistoric marvel, just 25 miles down the road. The stone circle here is actually much larger, though less sophisticated, and receives far fewer visitors. Pair this with your visit to Stonehenge.

www.english-heritage.org.uk

THE CHAUVET CAVE DRAWINGS, FRANCE

The Chauvet Cave in the Ardèche region of South-west France contains some of the greatest masterpieces of prehistoric art on the planet. The oldest known drawings, etched onto the cave walls with simple horse-hair brushes, charcoal and stones, were created by hunter-gatherers roughly 30,000 years ago – at a time when Europe was covered in 9,000 feet of glacier ice and giant aurochs still roamed the Earth. They are the oldest figurative cave drawings in Europe, and among the most ancient, sophisticated and well preserved in the world.

But they are more than just works of art. These drawings represent the birth of human creativity and imagination. They mark a turning point in our evolution. To see them is to look directly into the soul of our most primitive ancestors. And the more we look, the more we see ourselves reflected.

The Chauvet Cave was first discovered in 19...