![]()

PART I:

GROWING UP IN SCIENTIFIC LONDON

• CHAPTER 1 •

THE STREETS OF LONDON

Faraday was born on 22 September 1791 in Newington, south of the Thames in Surrey, near the Elephant and Castle and within shouting distance of the Old Kent Road. His father James Faraday was a journeyman blacksmith, recently married to Margaret Hastwell, a farmer’s daughter. They were recent arrivals in London, being originally from the village of Clapham in Yorkshire. They did not stay long in Newington. By the time Faraday was five they were settled into rooms above a coach house in Jacob’s Well Mews, off Manchester Square. James worked in a smithy in nearby Welbeck Street. Faraday’s parents were followers of the Sandemanians, a small non-conformist sect outside the dominant Church of England, and his father formally joined the Sandemanian Church shortly after their arrival in London. Faraday would be a devout Sandemanian throughout his life, becoming an elder of the Church but also at one period being temporarily expelled from its ranks. In 1809, with Faraday in his late teens, the family moved again, to Weymouth Street near Portland Place, where James Faraday, never in good health, died about a year later. Life for the Faradays was a struggle. During one period of high corn prices in 1801 – as the war with France demanded its economic pound of flesh – young Michael was forced to subsist on a single loaf of bread a week. James Faraday’s ill health meant that he was often unable to complete a day’s work.

Faraday’s early education was basic. As he recalled himself: ‘My education was of the most ordinary description, consisting of little more than the rudiments of reading, writing, and arithmetic at a common day-school.’ He was probably quite lucky to have received even as much of a rudimentary education as that. Times were hard and even the most basic education cost money. Literacy rates amongst London’s poorer classes at the beginning of the 19th century were not high. As a journeyman blacksmith – someone who worked for a master rather than being an independent master craftsman himself – it is unlikely, particularly given his recurrent ill health, that James Faraday earned much more than twenty shillings a week at the best of times. Little more is known about Faraday’s early childhood. When he was not at school, his time was passed at home or on the streets, playing marbles in nearby Spanish Place or looking after his little sister playing in Manchester Square. Given his family’s relative poverty, it is unsurprising that the young Michael Faraday was expected to make his own economic contribution to the family finances as soon as he was able. In 1804, when Faraday was thirteen, a bookseller, George Riebau, who kept a shop just around the corner from Jacob’s Well Mews at No 2 Blandford Street, hired him as an errand boy.

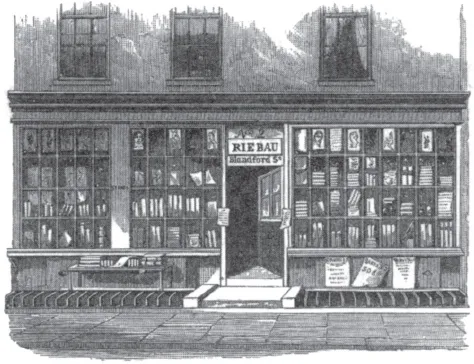

On 7 October 1805, after he had been working as his errand boy for about a year, Faraday was indentured as an apprentice to George Riebau to learn the trade of bookbinder and stationer. Faraday and his family were lucky. Apprenticeships into a good trade like this were highly prized and often kept within the family circle. They were even luckier that Riebau agreed to waive any payment for the apprenticeship, in view of Faraday’s ‘faithful service’ as an errand boy. As an apprentice, Faraday was expected to live with his master and mistress for a number of years and learn the rudiments of his master’s trade. At the end of the period – typically seven years – he would produce a masterpiece demonstrating his proficiency in the craft, and would become a journeyman, judged competent to seek employment in the trade in his own right. Riebau was clearly a good master and Faraday seems to have flourished under his tutelage. About halfway through the apprenticeship, his father noted that his son was ‘very active at learning his business’ after a few teething troubles at the beginning of his term. He had ‘rather got the head above water’ and had two junior apprentices under his command.

Illustration 1: George Riebau’s bookshop on Blandford Street. Faraday worked here for several years as a bookbinder’s apprentice, and first started to become interested in electricity.

London booksellers’ shops were important and interesting places to be in the turbulent early years of the 19th century. They were far more than simply places where Londoners went to buy books. They were also significant meeting points for the metropolis’s underground network of radical political agitators and rabble-rousers. Early 19th-century booksellers, like their 18th- and 17th-century predecessors, did more than just sell books. They often published them as well. There was a flourishing black market trade in the early 19th century in politically seditious and pornographic pamphlets and tracts. Political hacks and subversives, stridently demanding the rights of man, published filthy broadsides, condemning the corruption and mutual back-scratching of Regency culture in general and of William Pitt the Younger’s reactionary and repressive regime in particular. George Riebau certainly had a hand in this under-the-counter trade. He was part of a network of illicit publishers and pamphleteers churning out a steady stream of anti-establishment literature aimed at radicalising the working classes and chipping away at the bastions of power and privilege. Working away in his shop, the teenage Faraday would have witnessed London’s radical underworld in action. He would have seen the way that some of its members turned to science as a powerful weapon in the fight for social justice and political emancipation. In later life, Faraday was to have none of it.

What he also found out about – and clearly fell in love with – was science. As Faraday himself recalled: ‘Whilst an apprentice I loved to read the scientific books which were under my hands, and, amongst them, delighted in Marcet’s “Conversations in Chemistry”, and the electrical treatises in the “Encyclopaedia Britannica”.’ Jane Marcet’s Conversations in Chemistry (first published in 1806) was written in dialogue form, following a conversation on chemistry between a governess and her two female charges. It introduced the bookbinder’s apprentice to the chemical philosophy of Humphry Davy, who was to play a vital part in his life a few years later. Early 19th-century books were usually bought unbound. It was Faraday’s job to bind them. He clearly took advantage of the opportunity to read them as well, being an enthusiastic and indiscriminate reader. ‘Do not suppose that I was a very deep thinker’, he warned his Royal Institution successor, John Tyndall, ‘or was marked as a precocious person. I was a very lively imaginative person, and could believe in the “Arabian Nights” as easily as in the “Encyclopaedia”. But facts were important to me, and saved me. I could trust a fact, and always cross-examined an assertion.’ Inspired by his readings and what he found out about the latest developments in electricity (a topic that would certainly have fascinated the political radicals dropping in to Riebau’s shop as well), he started experimenting. ‘I made such simple experiments in chemistry as could be defrayed in their expense by a few pence per week, and also constructed an electrical machine, first with a glass phial, and afterwards with a real cylinder, as well as other electrical apparatus of a corresponding kind.’ With his master’s permission and money donated by his older brother, Robert, he also started attending his first lectures.

• CHAPTER 2 •

SCIENTIFIC LONDON

So what was out there for an impecunious young apprentice looking to discover science in early 19th-century London? Regency London had a flourishing scientific culture. A whole range of scientific institutions of various kinds prospered. There was a thriving culture of popular scientific lecturing. A scientific tourist with enough time on his hands, plenty of money in his purse and – crucially – the right introductions in his coat pocket could look forward to rubbing shoulders with some of the greatest scientific minds in Europe and seeing some real scientific wonders. A steady diet of popular scientific lectures and spectacular demonstrations had been a staple part of the metropolis’s coffee-house culture since at least the early 18th century. Such events continued to be a draw for fashionable and genteel audiences in the opening decades of the 19th century as well. Not only home-grown scientific lecturers, but a steady stream of foreign performers turned up on London’s scientific stages. Our scientific tourist, if he had visited London in 1803, could have witnessed the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini at work, for example. The nephew of Luigi Galvani (the discoverer of animal electricity – the eponymous galvanism) carried out electrical experiments on the body of an executed murderer, presided over by the President of the Royal College of Surgeons.

London science had its own social circle and its own hierarchy of institutions and activities. At its pinnacle at the beginning of the 19th century was the Royal Society. Founded in 1662 with a royal charter from Charles II, the Royal Society was from its beginnings a society of scientific gentlemen devoted to the increase of natural knowledge. In 1810 its President, Sir Joseph Banks, had been at the helm for more than 30 years. He had made a name for himself as a botanist and natural historian during Captain James Cook’s expeditions to the South Seas. Independently wealthy, he had used his money, his connections and the name he had made for himself as Cook’s botanist to place himself at the centre of a powerful network of scientific patronage with the Royal Society at its core. To Banks’s enemies, of whom there were quite a few by 1810, the Royal Society under his nepotistic regime typified everything that was wrong with metropolitan (and English) science. It was corrupt – Banks held most of the meagre public purse strings of English science in his own hands and doled the money out to his own protégés. It was aristocratic and dilettante in its attitudes and interests. For a new generation of meritocratically minded gentlemen of science who were starting to come to the fore of metropolitan science during the 1810s, the Royal Society looked like a fruit ripe for the picking.

The Royal Society’s Fellows – those who could put the magic letters FRS after their names – were a self-proclaimed philosophical élite. During the early 19th century the Society held its meetings at Somerset House on the Strand, where they had moved from a house in Crane Court in 1780. Meetings were ceremonial affairs, usually presided over by Sir Joseph Banks himself. Papers were read out by one of the Society’s secretaries rather than by their authors, before being formally presented to the Society. Elections to the prestigious Fellowships also took place at meetings, with potential Fellows being nominated by existing ones and put up to a vote of those present. There was no particular requirement that a potential Fellow should be an active man of science. As far as Banks and his cronies were concerned, power and patronage were just as good reasons as a scientific reputation for being made an FRS. The Royal Society held its meetings weekly during the winter months. There were no meetings during the summer when many of the Fellows would be found at their country estates rather than in the city. A bookbinder’s apprentice like Michael Faraday would have stood little or no chance of ever being admitted into the Royal Society’s Somerset House chambers. It was strictly a society for scientific gentlemen.

Only slightly lower down the social scale of London science during this period would have been the Royal Institution. The RI was a recent foundation, having been established only a few years previously in 1799 by a coterie of gentlemen, with the Royal Society President, Sir Joseph Banks, foremost in their midst. Inspiration for the new scientific institution had been provided by the American émigré and loyalist, Benjamin Thompson, who had been obliged to flee the former Colonies with the advent of American independence. Thompson’s plan had been to establish an institution for diffusing knowledge and new inventions and improvements, as well as ‘for teaching, by means of philosophical lectures and experiments, the application of science to the common purposes of life’. A mansion in fashionable Albemarle Street was purchased to provide a home for the new institution. The original plan had been for an institution that would provide scientific lectures aimed at all social classes. In his early drawings, Thomas Webster, the Institution’s architect, incorporated a staircase leading directly from the outside to the lecture theatre so that the city’s rude mechanicals could gain entry without mixing with their betters in the lobby. The continuing war with France and radical unrest at home soon started to make such plans for workers’ education look decidedly suspect, however. Webster found himself being ‘asked rudely what I meant by instructing the lower classes in science … it was resolved upon that the plan must be dropped as quietly as possible. It was thought to have a political tendency.’

The Royal Institution spawned a number of competitors, though none of them ever really succeeded in emulating the social and scientific exclusivity of the fashionable institution on Albemarle Street. The London Institution was founded in 1805 by a splinter-group from the Royal Institution, unhappy with that body’s aristocratic ethos and emphasis on agricultural improvement. As hard-headed city businessmen and professionals, what they wanted to foster was the union of science and commerce. Science and commerce combined, Charles Butler insisted in his oration at the laying of the foundation-stone of the Institution’s Finsbury Circus building, would ‘record the heavens, delve the depths of the earth, and fill every climate that encourages them with industry, energy, wealth, honour, and happiness:- To civilization, to virtue, to religion, they open every climate; they land them on every shore; they spread them on every territory.’ As well as the London Institution, other competitors to the Royal included the Surrey Institution near Blackfriars Bridge, where the chemist Frederick Accum lectured (and which possessed ‘an excellent library and a still more decent Laboratory’), and the Russell Institution in Bloomsbury, both founded in 1808. As well as drawing their inspiration from the Royal Institution, these smaller scientific institutions also modelled themselves on the growing body of provincial literary and philosophical societies that were so much in vogue during the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries. The first of these, the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, had been founded in 1781.

Faraday’s chances of getting inside the Russell or Surrey Institutions, or even the London Institution, while probably higher than his hopes of entering the Royal Institution’s gilded portals, were still not very promising. By the 1810s, London boasted its own Literary and Philosophicals as well. The Hackney Literary and Philosophical Society, founded in 1810, met every Tuesday for scientific conversation and lectures on subjects ranging from literature through chemistry and galvanism to mathematics. The Marylebone Lit. and Phil. was founded a little later, with a lecture theatre in Portman Square that could accommodate 600 people. In 1806, the London Chemical Society was established at Old Compton Street in Soho with 60 members on the books. It had its own well-equipped chemical laboratory and provided a good institutional base for the likes of Frederick Accum before he moved on to the Surrey Institution. The London Philosophical Society had its origins as early as 1794 in a group of enthusiasts centred around the watch- and instrument-maker Samuel Varley. By 1811 the Philosophical Society of London occupied the Royal Society’s old quarters in Crane Court. Unlike their Royal predecessors, the new incumbents promised ‘to foster genius, to eradicate unphilosophic prejudice, to increase the knowledge of nature, and most, of man’.

Down at the very lower end of the scientific market-place – and therefore probably most accessible to someone in Faraday’s position – scientific shows of various kinds proliferated. The popular lecturer Adam Walker performed regular courses of twelve lectures each on ‘Natural and Experimental Philosophy’ at such unlikely venues as the King’s Head in the City and the Theatre Royal in Haymarket. Entry to his lectures cost a guinea for the course: still a considerable sum for an apprentice boy. Walker founded a mini-dynasty of popular scientific lecturers who were still active more than a decade later. Another prolific and popular performer was Mr Hardie, a surgeon based at Great Portland Square. Hardie gave his performances on anything from astronomy, chemistry or electricity to mathematics and medicine, at his own Theatre of Science on Pall Mall. As well as extended lecture courses, he offered single performances tailored to the impecunious enthusiast. Lecturers such as these, or others who performed at venues like the Lyceum or the Theatre of Astronomy on Catherine Street, were unabashedly popular, adapting their presentations to the expectations of their audiences and taking advantage of every opportunity to attract new customers. They were theatrical performances in every sense of the word.

This range of scientific activities and institutions sustained a burgeoning group of more or less peripatetic scientific lecturers in London. Very few popular scientific lecturers confined their activities to a single institution. They moved around from place to place and offered courses of their own independently as well. Success in London could provide the basis for a lucrative tour of the provinces. Similarly, lecturers who had made a reputation for themselves in the provinces gravitated towards London and its possibilities. A good example is Thomas Garnett, who had lectured across the Midlands and at Glasgow’s Anderson’s Institution before coming to London, initially as a Professor at the Royal Institution. After falling out with Benjamin Thompson he set himself up as an independent, working from his base on Great Marlborough Street and at Tomm’s Coffee House in Cornhill. His protégé, George Birkbeck (later to play a key role in establishing the London Mechanics’ Institution), similarly moved from the Anderson’s Institution to try his luck on the London lecturing circuit. Many players on the metropolitan popular scientific scene, like Garnett and Birkbeck (and the prolific Mr Hardie), were medical men and looked to providing lectures to medical students for a large part of their income.

Illustration 2: William Walker lecturing on astronomy at the English Opera House. Walker, the product of a mini-dynasty of spectacular scientific lecturers, was one of Faraday’s favourite performers.

Chemistry was another popular subject, again at least partly because of its attraction to medical students, but also because of its commercial potential. William Thomas Brande, a friend of Frederick Accum of the Surrey Institution, lectured on chemistry at the Great Windmill Street Theatre of Anatomy, paying particular attention to the application of chemistry to ‘the Arts and Manufactures’. Brande was one of relatively few popular lecturers making a living towards the lower end of London’s scientific market-place who succeeded in making it to the higher echelons. Brande eventually became an FRS, as well as Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution. London’s popular lecturers – the successful ones at least – kept a careful eye on the needs and expectations of their audiences. This is why medical subjects and chemistry (and geology and mineralogy too) were such common topics. They fulfilled the popular demand for useful knowledge. Not all popular lectures had to be so straightforwardly utilitarian, however. London’s lecture audiences liked a good show, and sciences such as astronomy or electricity could draw good crowds for that reason. Electricity in particular, with the invention of new devices such as Alessandro Volta’s voltaic pile in 1800, was a reliable crowd-pleaser. It was an excellent source of spectacular displays of nature’s powers – and of the lecturer’s own powers over nature.

• CHAPTER 3 •

FIRST STEPS IN SCIENCE

So what do we know about Michael Faraday’s early forays into London scientific culture? We know that he took full advantage of his position in George Riebau’s bookshop to read scientific books and journals as they came his way. We know that he constructed various pieces of scientific equipment – such as an electrical machine for generating static electricity – and carried out experiments. ...