![]()

1.

Fort Lee: Legend and Reality

STUDIO TOWN 1:

Fort Lee, Movies’ Battleground, and its Glamorous First Days

Sleepy Borough Here Became Scene of Producers’ War

1st Wild West

Its ‘Prairies’ Long In Use Before The Studios Went Up

By Edmund J. McCormick

(from Bergen Evening Record, July 8–12, 1935)

Sprawled out on the top of the majestic Palisades that wall the Hudson on the West, under the shadow of the George Washington Bridge from New York City is the little town of Fort Lee.

Here in the shadows of New York skyscrapers are fertile fields that give to the town its principal industry, farming. Serving as a severe contrast to its rural life is a giant stretch of steel, the George Washington Bridge that joins the cliff town to New York City, pouring into the small town thousands of cars a day.

At Fort Lee years ago when the colonies were fighting England in the war for independence was located one of the most formidable forts in the East, Fort Constitution.

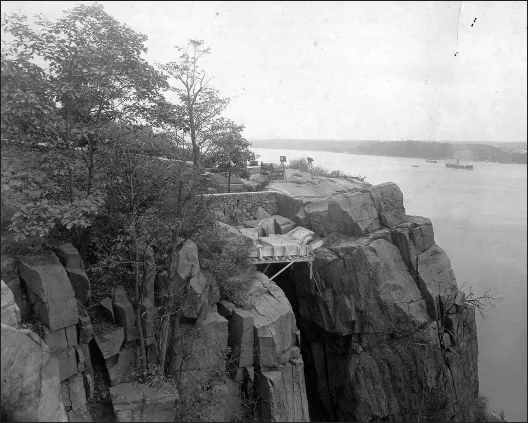

The Palisades, looking south to where the George Washington Bridge now stands.

Battleground again

Protected by the natural rock wall hundreds of feet high, the fort was one of the colonists’ strongholds. It was here that General Nathaniel Greene, greatly outnumbered, put up a gallant fight, finally going down to defeat before England’s Lord Cornwallis and where General Anthony Wayne was turned back in his attempt to capture the cliff fort.

Years later the town was again to become a battleground. Quite a different struggle, the conflict was waged between shrewd businessmen fighting with film and camera for the life of a new born industry, motion pictures.

In 1907 Sid Olcott, right hand man at Kalem’s New York motion picture studio, discovered a new Wild West lying in the shadow of New York City. Around Fort Lee were acres of delicious scenery, dense woods, steep slopes, distant mountains, open plain marsh, sheer hundreds of feet of solid rock rising high above the Hudson, and to put the icing on the cake was the town itself: dirt roads, dirt sidewalks, and old fashioned houses could be found in plenty. When Olcott saw the cliff town he knew it was the spot for Kalem’s western pictures, so the Kalem Company, with horses and tepees, came across the Hudson.

Griffith came in 1908

In the trail of Kalem in 1908 came D.W. Griffith with the Biograph Company, bringing with him Lillian and Dorothy Gish, Mary Pickford and Mack Senett.

The center of gathering for the companies on location was at Rambo’s Hotel, situated on an ill kept dirt road called Rambo’s Lane. On the upper floor of the small hotel were the rooms where the actors dressed. In the rear yard tables were set up for the companies to eat; here knights and ladies sat with Indians under the shade of apple trees that sided the tables. In the background could be seen a three-story frame house, the home of Maurice Barrymore.

An old property man who worked with Griffith and Kalem, and who still lives in a small house in back of Rambo’s, prepared the stage for the first picture Griffith directed.

It was a Biograph picture called The Adventures of Dolly.

“Griffith wasn’t the least bit nervous”, the old property man said. “We put everything in place up on Hammett’s Hill and were wondering what would happen. But the minute he walked on the scene we knew we were working for a real master. He gave orders clear and direct and had the whole thing done in a couple of days. [N.B. This may actually be a recollection of the filming of The Battle; see the account in The Palisadian reprinted on page 66.] Griffith liked soldier pictures. I’ve seen the time when he had seven hundred soldiers fighting at once – and that was a big crowd for those days. Kalem’s specialty was Indians. It got so after a while that if the day was clear I’d know Kalem would call from New York and say ‘Teepees’ – then I’d rush over with the wagon and fetch a couple of dozen, set them up here and there and we would be ready to go in no time. They weren’t particular then.”

Alice Joyce made her debut in motion pictures riding a horse for the Kalem Company in 1909. Another Kalem horseman was Robert Vignola who later directed Marion Davies in When Knighthood Was In Flower.

Fort Lee tolerated this violent disturbance of its former peaceful dignified life with a patient indifference. It would end in a short while, the town reasoned, so let them be. But the disturbance didn’t end – it became increasingly violent as the movie makers found that people would pay to see their pictures whether they were good or bad.

The rise and fall of Fort Lee, the film town, is a legend which has been told and retold for generations. As early as September 1921, Filmplay Journal published a photo essay on “Fort Lee, the Deserted Village”, highlighting the sudden abandonment of several large studio facilities (the obituary was a bit premature). The New York Times Magazine reported on “Ghosts in the Cradle of the Movies” on May 31, 1931, a piece which contrasted the beginnings of the motion picture industry with the “ghastly cemetery … of scaling concrete, crumbling brick, warped steel and shattered glass” now to be found there. Irving Browning’s account of his visit to “A Crumbled Movie Empire” appeared in the August 1945 issue of American Cinematographer. Browning, a veteran cinematographer, walked through the ruins of the studios with his friend Francis Doublier. Depressing photos of burned-out industrial buildings and weed-ridden vacant lots illustrated the piece. In February of 1951 film historian Theodore Huff, an Englewood native, published “Hollywood’s Predecessor” in Films in Review; Huff had already made a brief documentary film on the same theme, Ghost Town: The Story of Fort Lee, in 1935. Both were clearly influenced by “Studio Town”, a series of articles which appeared in Huff’s local paper, The Bergen Evening Record, between July 8 and 12, 1935, and which are reprinted here for the first time. This remarkably astute survey of Fort Lee film history was written by one of the Record’s staff writers, Edmund J. McCormick. He appears to have interviewed local residents, trawled through clipping files, and tapped at least one industry insider, publicist Paul Gulick, whose name appears on illustration credits. McCormick does introduce one significant error when he claims that D.W. Griffith’s first film as a director, The Adventures of Dolly, was shot in Fort Lee (it was actually Sound Beach, Connecticut). Perhaps he misunderstood what his informant meant by “Griffith’s first picture.” We have slightly reorganized the text at one point, where the original editorial work garbled the correct order of several paragraphs, and deleted one irrelevant aside.

Studios go up in 1908

Rough wooden shacks had been erected at Fort Lee, but nothing that resembled a studio until Mark H. Dintenfass promised the Edison Company in 1908 that he wouldn’t make any more motion pictures.

In 1903 Mark Dintenfass was a salt herring salesman working for his father. A few [years] later he was a proprietor of Philadelphia’s second movie house, a small store with little over a hundred seats. Holding title to a camera after an experiment with talking pictures in his playhouse had failed, Dintenfass decided to sell his theater and become a producer. He opened up the Actophone Studios in New York.

Scaffolding, complete with mattresses, intended to safeguard actors during stunt action on the Palisades (c. 1918).

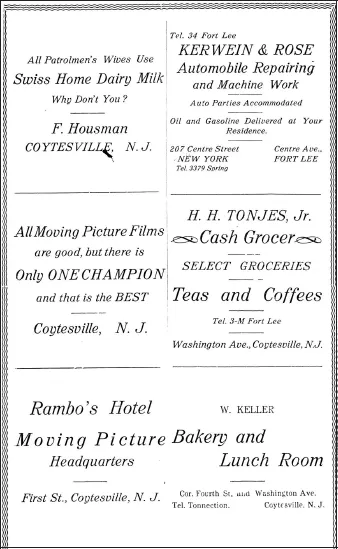

A page of advertising from the program of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association of Bergen County’s Second Annual Picnic and Games, Cella’s Park and Casino, 4 October 1911. Rambo’s and the Champion Studio take space along with other local businesses.

His movements were carefully watched by a powerful group of movie makers who had pooled their patents, among which was the patent for the Latham Loop, heart of the motion picture camera.

The movie trust squeezed out independents by virtue of its practical control of all motion picture cameras. Bold independent producers had to resort to all [manner of] tricks to hide from the rubber sneakered patent trust investigators. Some hid in cellars, others concealed cameras in scenery or under cloth hoods.

He couldn’t quit

Dintenfass botched the job of hiding his camera and was caught one day by an Edison man. After loud arguments in which the Edison Company always won, Dintenfass, in return for a promise from the trust that he wouldn’t be prosecuted in court, said he would forget that he ever wanted to be a producer.

But it was in his heart. He couldn’t give up his ambition so easily. A short while later, well hidden in a shanty at Fort Lee, he continued to grind out pictures. In 1909 [actually 1910 - ed.] he built the first studio at Fort Lee, called his company Champion, and started production.

Fort Lee’s first studio wasn’t an impressive structure when compared with the giant studios of today. But its 150 feet of shingled building with small glass studio was significant then for it marked the beginning of a period when producing companies were about to band together in settlements.

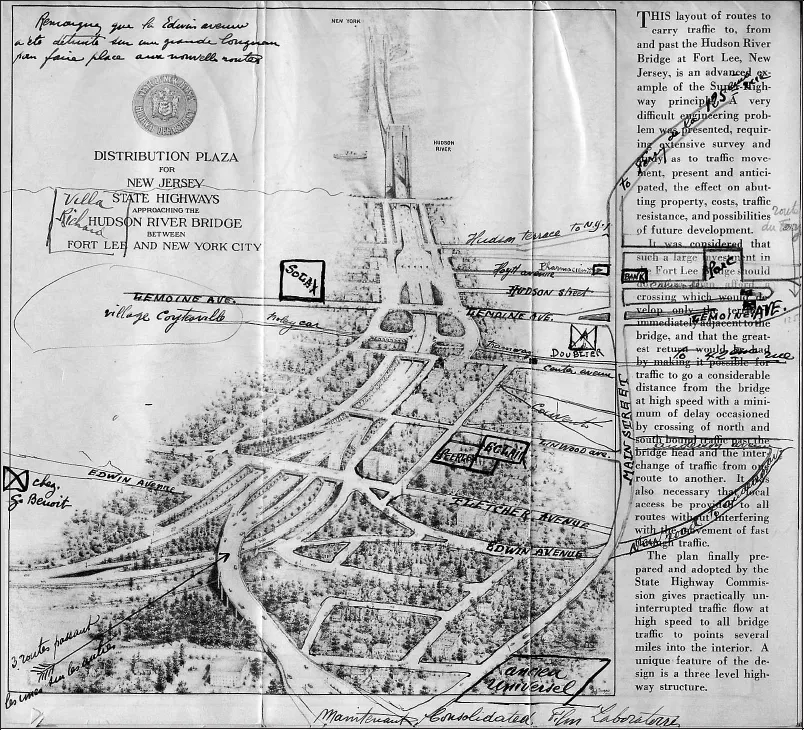

A map of the approaches to the proposed Hudson River (George Washington) Bridge, annotated in the late 1920s by Eclair animator Emile Cohl, indicating the locations of various studios and the homes of other members of the French filmmaking community. Cohl’s own house on Hoyt Avenue, not shown, would have been directly under the main bridge approach.

In 1909 there were several minor centers of the industry, but no large groupings as were later to form at Fort Lee and Hollywood. Largest number of companies was found in New York City where Vitagraph, Edison, Kalem, Biograph and Carl Laemmle’s Imp roosted. Chicago and Philadelphia ranked as secondary centers.

California already had several companies on location. The movement to the West was headed by the Selig Company in 1907. Essanay followed with its Wild West Company in 1908.

Baumann and Kessel deserted their Florida and Fort Lee locations for the West in 1909. D.W. Griffith went west with Biograph a year later.

The pictures taken at the period when Champion started were simple affairs consisting of one or two reels. The subjects were mainly thrillers involving the cowboy and Indian theme. Few pictures cost over $10,000 to produce.

STUDIO TOWN 2: The Public Becomes Critical; Fire, Movies’ Menace, Strikes.

Stupid Plots, Monotonous Stories Bore Audiences As Novelty Of Film Wears Off Éclair Studio Leveled

The procedure that evolved as a movie maker’s formula for success in terms of dollars was many pictures at lost cost. Plots were seldom considered seriously. They grew as the pictures went along. The use of a story prepared in detail before the picture was taken was not to come for several years.

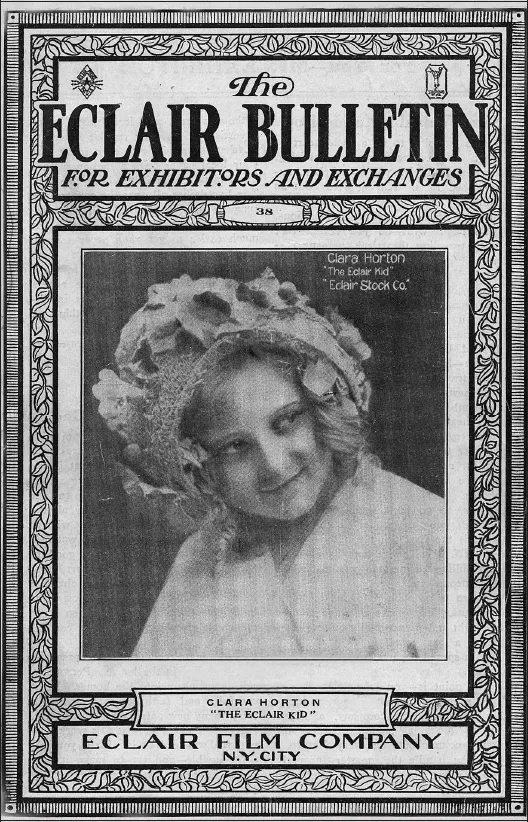

The Éclair Bulletin for March, 1913. Many studios would publish their own promotional house papers.

A typical story of the period is Caprices of Fortune starring Barbara Tennant and Alec Francis. The picture was produced by the Eclair Company, the second company to locate at Fort Lee. It was a story of a poor young man madly in love with a wealthy second cousin. He asked her mother for her daughter’s hand but she, reminding him of his low station in life, refused. He was considerably shaken but mustered up enough strength to ask, “Auntie, if I make my fortune, may I hope to marry Bertha?” He left to make his fortune in Homestead, Pennsylvania. From there he drifted to the West and then to Mexico. Finally he won money in a lottery and went back to marry his aunt’s maid.

Eclair, the producer of this bit of drama, came to Fort Lee in 1911. It was the American branch of the mildly profitable Cinema Éclair in Paris, a company headed by Charles Jourjon. Foreseeing the golden harvest to be reaped in America, Charles Jourjon capitalized a company for $1,250,000, set aside $200,000 for buildings and equipment, and set the carpenters to work at Fort Lee.

Francis was star

The late veteran of the screen, Alec Francis, was the mainstay of the company. Supporting him in his pictures was leading lady Barbara Tennant.

Éclair’s pictures were usually only a reel long. One spectacle called The Land of Darkness or Through the Bowels of the Earth set a high-mark in the company’s history. It was advertised as staged “at a cost of $50,000 – 200 people in its mighty cast” – but cutting both figures twice would give a more accurate picture of the spectacle’s proportions. If the story ran short, as it usually did, Éclair would tack on enough footage of a nature study to even up the reel.

The year that brought Éclair on the scene at Fort Lee also brought Herbert Blanche [i.e. Blaché] who erected a series of buildings in the cliff town and opened up a producing company called Solax. But Solax was to be a dull star in the constellation of youngsters who sprang up during this period. Hanging on for years, finally passing out of the scene entirely in the early twenties after a serious fire, the company reached only mild success pushing Olga Petrova to stardom during the vampire period.

Champion, Éclair and Solax were all members of the independent group wh...