eBook - ePub

Art in Motion, Revised Edition

Animation Aesthetics

Maureen Furniss

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Art in Motion, Revised Edition

Animation Aesthetics

Maureen Furniss

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Art in Motion, Revised Edition is the first comprehensive examination of the aesthetics of animation in its many forms. It gives an overview of the relationship between animation studies and media studies, then focuses on specific aesthetic issues concerning flat and dimensional animation, full and limited animation, and new technologies. A series of studies on abstract animation, audiences, representation, and institutional regulators is also included.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Art in Motion, Revised Edition an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Art in Motion, Revised Edition by Maureen Furniss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & VideoPart 1

FUNDAMENTALS

1

Introduction to animation studies

Although Cinema Studies has developed greatly since its general introduction into university programs during the early 1960s, Animation Studies has largely remained on the sidelines – while colleges and universities have offered animation production courses, for many years the study of the form’s aesthetics, history and theory was relegated to the status of an elective ‘special course’ offered only on an occasional basis or not taught at all.1 In some cases, when animation was acknowledged, it was subsumed under another subject matter, such as avant-garde film. Discussions of James Whitney, Jordan Belson, Stan Brakhage or Pat O’Neill, all of whom used frame-by-frame animation techniques at some point, probably are found primarily in that context.

The denigrated status of Animation Studies in the university is largely due to the belief held in many that animation is not a ‘real’ art form because it is too popular, too commercialised, or too closely associated with ‘fandom’ or youth audiences to be taken seriously by scholars. This impression is faulty because there is a wide range of animation that is not commercially – or child – oriented and, in any case, these areas also merit study.

Fortunately, the situation of Animation Studies has improved. A significant factor has been the influence of post-modernism on Media Studies, which has helped legitimise the study of popular forms of entertainment. Also, people are realising that there is an immediate need to document previously marginalised areas, including animation history, which is slipping away quickly.2 Many artists from the early days have died before their contributions have been adequately recorded; films and cels, many of the early ones on nitrate, are disintegrating; and documentation material, once believed to be of little value by studios, has been discarded or housed unavailable to historians (and often without any organisation) in studio warehouses. For many years, the documentation of animation history largely was carried on by a relatively small and cloistered group of individuals that included serious fans, collectors, and historically minded practitioners. However, some organisations that emerged during the latter 20th century concerned themselves with the preservation of animation history. Among the first was l’Association Internationale du Film d’Animation, generally known as ASIFA (the International Association of Animated Film), which was founded in 1960 and continues to operate on an international level with local chapters in many parts of the world. ASIFA groups have held animation retrospectives and have published a wide array of writing on the topic of animation history. In the late 1960s, the now gigantic organisation SIGGRAPH emerged as a small special interest group from its parent organisation, the Association for Computing Machinery. SIGGRAPH began holding conferences in the mid-1970s and has been responsible for a range of print and online publications; part of its aim has been the recording of computer animation history.

The late 1980s saw increasing concern with the preservation of animation as an art, among both industry professionals and scholars. Walter Lantz was among the first to speak up for the future of animation. With his financial assistance, the American Film Institute hosted two conferences, in 1987 and 1988, and published two anthologies of critical writing on animation.3

At about the same time, Harvey Deneroff founded the Society for Animation Studies (SAS) (http://animationstudies.org), which has held annual conferences since 1989. Although SAS members and others began to produce a stream of animation research in the 1980s, for some years it remained difficult to place essays on animation in the majority of media journals, which are geared toward live-action motion pictures. As a result, a lot of animation research languished undeveloped and without proper distribution. To address this problem, Animation Journal (http://www.animationjournal.com), the first peer-reviewed publication devoted to animation studies, was founded in 1991; the journal publishes history, theory and criticism related to animation in all its forms.4

Another sign of growth in the field was the establishment of Women in Animation (WIA) by former Animation Magazine publisher Rita Street in late 1993. This non-profit, professional organisation is dedicated to preserving and fostering both the contributions of women in the field and the art of animation. The organisation of a historical committee was among the first of WIA’s activities and an oral history program has begun to document the work of women in the field, which for years has been undervalued.4 The above list includes only a few milestones in the growth of animation studies, which is more thoroughly documented elsewhere.

DEFINING ANIMATION

One of the concerns that has resurfaced periodically in animation scholarship relates to definition. Before one attempts to understand the aesthetics of ‘animation’, it is essential to define its parameters: just what is meant by the term?

In ‘Animation: Notes on a Definition’, Charles Solomon discusses a variety of techniques that he says can be called ‘animation’.5 He finds that ‘two factors link these diverse media and their variations, and serve as the basis for a workable definition of animation: (1) the imagery is recorded frame-by-frame and (2) the illusion of motion is created, rather than recorded’.6 Ultimately, he finds that ‘filmmaking has grown so complicated and sophisticated in recent years that simple definitions of techniques may no longer be possible. It may be unreasonable to expect a single word to summarise such diverse methods of creating images on film’.7

One of the most famous definitions of animation has come from Norman McLaren, the influential founder of the animation department at the National Film Board of Canada. He once stated:

Animation is not the art of drawings that move but the art of movements that are drawn; What happens between each frame is much more important than what exists on each frame; Animation is therefore the art of manipulating the invisible interstices that lie between the frames.8

In this case, McLaren is not defining the practice of animation, but rather its essence, which he suggests is the result of movement created by an artist’s rendering of successive images in a somewhat intuitive manner. Although McLaren wrote of ‘drawings’ in his original definition, he later indicated that he used that word ‘for a simple and rhetorical effect; static objects, puppets and human beings can all be animated without drawings …’.9

Both of these individuals has a different interpretation of the term ‘animation’. McLaren discusses an inherent aesthetic element (movement – an issue that will be expanded on later in this book), while Solomon attempts to illustrate the borders of the practice, to display the qualifications that allow an object to be discussed as animation. Despite these and other attempts, arriving at a precise definition is extremely difficult, if not impossible. It is probably safe to say that most people think of animation in a more general way, by identifying a variety of techniques such as cel animation, clay animation, stop-motion and so forth.

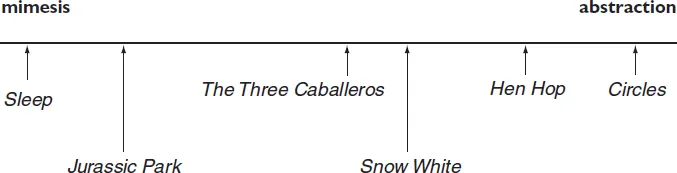

One way to think about animation is in relation to live-action media. The use of inanimate objects and certain frame-by-frame filming techniques suggest ‘animation’, whereas the appearance of live objects and continuous filming suggest ‘live action’. However, there is an immense area in which the two tendencies of overlap, especially when an individual is writing on the subject of aesthetics. Rather than conceiving of the two modes of production as existing in separate spheres, it is more accurate for the analyst to think of them as being on a continuum representing all possible image types under the broad category of ‘motion picture production’ (Fig. 1.1).

In constructing this continuum, it is probably best to use more neutral terms than ‘animation’ and ‘live action’ to constitute the ends of the spectrum. Although the terms ‘mimesis’ and ‘abstraction’ are not ideal, they are useful in suggesting opposing tendencies under which live action and animated imagery can be juxtaposed. The term ‘mimesis’ represents the desire to reproduce natural reality (more like live-action work) while the term ‘abstraction’ describes the use of pure form – a suggestion of a concept rather than an attempt to explicate it in real life terms (more like animation).

There is no one film that represents the ideal example of ‘mimesis’ or ‘abstraction’ – everything is relative. A work that combines live action with animation, such as The Three Caballeros (directed by Norman Ferguson, 1943), would appear somewhere in the middle of this continuum, while a documentary like Sleep (directed by Andy Warhol, 1963), a real-time account of a person sleeping, would be far to the side of mimesis. A live-action film employing a substantial amount of special effects, such as Jurassic Park (directed by Stephen Spielberg, 1993), would appear somewhere between Sleep and The Three Caballeros. On the other hand, a film like Hen Hop (directed by Norman McLaren, 1942), which contains line drawings of hens whose bodies constantly metamorphose and break into parts, would appear on the other side of the spectrum, relatively close to the abstract pole because the film is completely animated and its images are very stylised. Even further toward abstraction would be Kriese (Circles; directed by Oskar Fischinger, 1933), which is composed of circular images that are animated to the film’s score. However, the Disney animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (directed by David Hand, 1937) has a relatively naturalistic look and employs some characters based on human models, so it would appear on the abstraction side but closer to the mid-point of The Three Caballeros. While it may seem strange to describe Snow White as an example of an ‘abstract’ work, its characters and landscapes can be described as caricatures, or abstractions of reality, to some extent.

Actually, the placements suggested by this description are somewhat arbitrary. There is no exact spot where any one film should appear and it is completely reasonable that various people might argue for different placements than the ones described here. The point is that the relationship between live action and animation, represented by mimesis and abstraction, is a relative one. They are both tendencies within motion picture production, rather than completely separate practices.

Fig. 1.1 A live action – animation continuum

One advantage of this kind of system is that it facilitates discussion of someone like Frank Tashlin, whose work overlaps the realms of both live-action and animation. It has been said that his animated works for Warner Bros., Columbia and Disney during the 1930s and 1940s are strongly influenced by live-action conventions, while the live-action features he directed after his career in animation tend to be very ‘cartoony’ in nature. One can easily see the crossover in examining one of his characters, Rita Marlow (played by Jayne Mansfield), in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter (1957). With her big hair, large bosom, small waist and exaggerated manne...