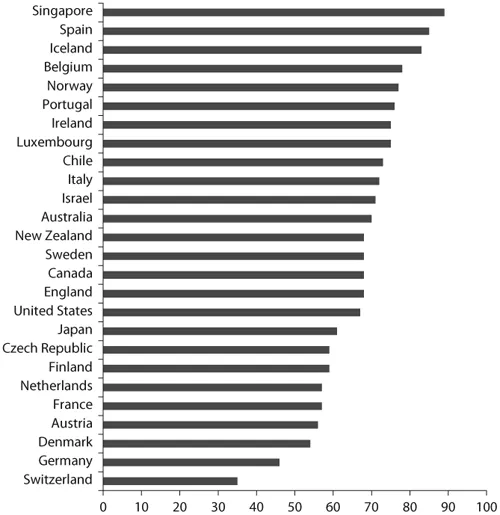

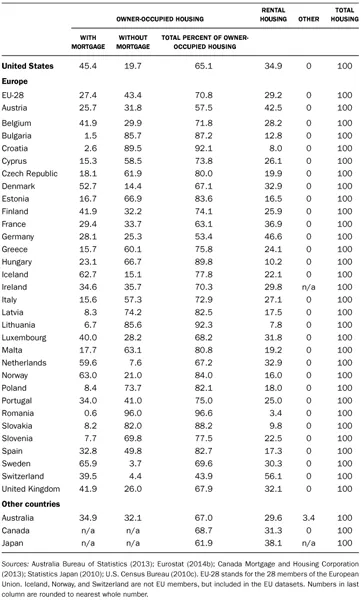

America has long prided itself on being a “nation of home owners,” as FDR once put it (quoted in Kelly 1993, 171). This statement is true in the sense that most American families—two-thirds of them—own their homes. But the phrase also implies something else: that in its success in securing mass homeownership, America is exceptional among other nations. This notion, however, is inaccurate. True, homeownership rates were dramatically higher in the United States than in other parts of the western world some 100 years ago. In the late 1800s, 48 percent of families owned their homes, a figure reflecting the unusual affluence of American middle-class society at the time. After a dip during the Great Depression, the rates grew steadily to reach the current figure of about 65 percent by 1970 (e.g., Gale, Gruber, and Stephens-Davidowitz 2007). By contrast, in the early 1900s, the homeownership rate in England was only 10 percent (Hicks and Allen 1999; Home 2009). The situation was similar in most other West European countries, where homeownership rates did not increase significantly until after World War II. However, the historic contrast no longer stands. In homeownership, today’s America is but a middle-range country (Munjee n.d.), ranked seventeenth out of twenty-six “economically advanced countries” covered in a recent report (Pol-lock 2010). The report shows, in fact, twelve “economically advanced” countries whose homeownership rates are at or exceed 70 percent, with Singapore (89 percent) leading the pack, as figure 1.1 illustrates. The average homeownership rate among the European Union’s (EU) twenty-eight members is over 70 percent as table 1.1 shows. The United States, at 65 percent, would come nearly at the tail end of the chart, following most European nations, as well as Canada and Australia.1 But if not in ownership per se,2 are U.S. housing patterns distinct at all, and if so, in what way?

Home, Sweet (Single-Family) Home

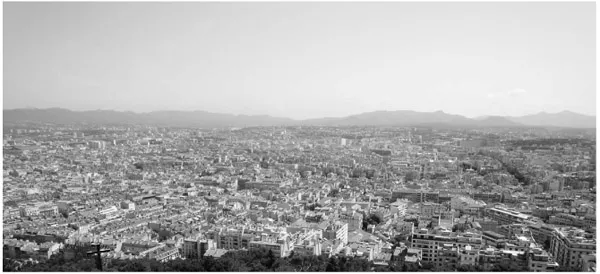

What makes Americans special is not their homeownership rates but the fact that they reside, in unusually high numbers, in detached single-family homes. As Table 1.2 shows, over two-thirds of American housing comprises single-family homes. True, some of the European numbers are higher, on both sides of the former Iron Curtain (e.g., in Ireland, the UK, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, Hungary, Croatia and Slovenia), but note that these numbers generally drop sharply when we separate the detached from the attached family homes. In detached single-family homes—homes with private yards—the United States shoots nearly to the top, reaching nearly twice the EU average (63 as compared to 34 percent).3 And perhaps surprisingly, although the United States rate of single-family housing is similar to, say, that of Norway or post-communist nations such as Hungary or Romania, it dwarfs that of the United Kingdom, which stands at only 26 percent. Moreover, one can dig into the high European numbers a bit deeper and detect a different story. For various historic, geographic, and economic reasons, Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, the two primary regions with high detached single-family housing rates, have been less urbanized than the rest of the continent and the United States (e.g., Bairoch and Goertz 1986; Szelenyi 1996). Notwithstanding some recent trends toward urban decentralization, in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia detached single-family housing is often associated with small towns and villages, with the rural way of life. In contrast, large metropolitan areas are dominated by multifamily buildings. In the large cities of nations that were once under the Soviet thumb, multifamily buildings constructed of prefabricated panels after World War II house the majority of the population: in the Romanian capital of Bucharest, for instance, 82 percent of people live in such buildings (Hirt and Stanilov 2009). In the large cities of central and western Europe, Spartan mass housing is typically less dominant, but the large majority of the population dwells in multifamily structures: 81 percent in Berlin, 97 in Rome and in Madrid, and 99 in Paris4 (Urban Audit n.d.). Compare this to cities in the United States. Only New York comes close, with 80 percent of its population residing in multifamily housing (the number drops, though, to 62 if we consider New York’s metropolis as a whole). In Chicago, the respective numbers are 65 percent (city) and 37 (metropolis), in Seattle 46 (city) and 29 (metropolis), in New Orleans 31 (parish) and 21 (metropolis), and in Philadelphia only 25 (city) and 20 (metropolis) (U.S. Census Bureau 2011b).5 (Figures 1.2 and 1.3 illustrate the contrast between European and American housing patterns.) The differences between Europe and the United States grow sharper if we take into account that even in U.S. cities where a significant percentage of the population lives in multifamily housing, this type of housing occupies only a minor portion of the total urban land area (the rate is typically in the single digits), whereas a very large part of the area designated for residential uses is taken by land zoned specifically for detached single-family homes— often about half the city, and the number is much higher in the suburbs.6 (More on this in the next chapter.)

TABLE 1.1 Percentage of households in owner-occupied and rental housing in the United States and select western nations

TABLE 1.2 Percentage of housing by dwelling type in the US and select western nations

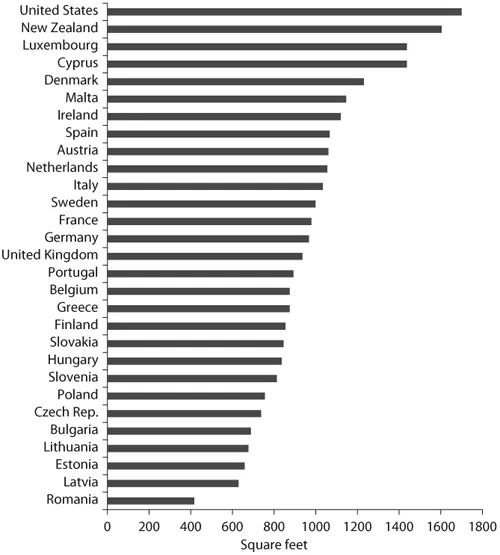

Americans are also champions when it comes to the size of the homes they live in: from the viewpoint of almost the entire rest of the world, American homes are unusually spacious. The average size of a new dwelling has more than doubled since the 1950s, from about 1,000 to 2,300 square feet (even though the average household size has shrunk; Wilson and Boehland 2005). The latest reported median is about 1,700 square feet (U.S. Census Bureau 2011a).7 This well exceeds most of the available numbers for European countries and those for other nations for which I could find data (only the New Zealand statistic comes close to that of the United States; see figure 1.4).8 American dwellings are also surrounded by ever-expanding private yards featuring what is practically a mythical entity around the world: the perfectly manicured green American lawn.9 The average size of American residential lots has increased from about 6,000 square feet in the 1930s (Adams 1934, 65) to about 14,000 square feet in 1982 to about 18,000 square feet in 2008—a generous figure.10

To the unusually spacious individual houses positioned on unusually large private lots, add America’s millions of other large buildings built at large distances from each other and the extraordinary amount of space created to support another aspect of Americans’ private lifestyles—the ability to travel vast distances alone (i.e., in an automobile).11 In some estimates, “car-architecture” (spaces taken by highways, roads, parking, driveways, gas stations, etc.) in U.S. cities and suburbs occupies well over a quarter of the total built landscape (Ellin 2006, 47). The result is a potentially distinct U.S. model of urbanism (or suburbanism, to be more precise): an urbanism of such low density that it could well be seen as nonurban by outsiders. Forget America’s image as a land of downtowns with skyscrapers (these occupy a miniscule portion of the total built landscape, as they do, of course, in many other countries) and look at overall densities. Metropolitan Atlanta’s density is about 700 people per square mile; this is more than ten times lower than Moscow’s and Paris’s and 100 times lower than Hong Kong’s. The density of America’s most populated Metro, New York, which had about 2,000 people per square mile in 2000, is about five times lower than Prague’s, ten times lower than Mexico City’s, and forty-five times lower than Dhaka’s. In fact, as figure 1.5 illustrates, it is difficult to graphically represent the population densities of American metro areas in a way that compares them to that of other cities around the world: the U.S. numbers come too close to zero.

What explains these distinct features of the U.S. built environment? Why the unusually low population density? And why the unusual domination of a particular housing form, the detached single-family home, placed at an arm’s-length distance from its neighbors? Ask a casual observer and you will get the same answer:12 America has always had more plentiful land than others; this is what distinguishes America from other nations. As Gertrude Stein put it, “In the United States there is more land where nobody is than where anybody is. This is what makes America what it is” (quoted in Platt 2004, 6). There is certainly a long history of such perceptions. American land developers of all eras learned to capture and play with such perceptions again and again, to their benefit (Figure 1.6 offers a contemporary illustration of how developers use these perceptions).

At the dawn of the twentieth century, when the English and the Germans were beginning to seriously worry about sprawling cities and preserving the countryside, American urban policy makers could still proudly proclaim that there is “no danger [in America, unlike in Europe] that this great urban population will cause a national land shortage” (Ihlder 1927, 73). I will discuss the relationship between the perception of limitless land and the development of America’s early land-use laws in greater depth in chapter 5, but here I should just note that more than one excursion into U.S. urban forms, laws and institutions has started with land:

The existence of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.… The peculiarity of American institutions is, the fact that they have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people. (Turner [1893] 2008)

Land has never been a scarce resource in America. Its great abundance has been a powerful influence on American attitudes toward the land, its development, and attempts by government to control its use.… The general unconcern for the rate at which land is consumed by new development, born out of the confidence that the supply is virtually unlimited, has been called “the prairie psychology.” And it is not altogether fanciful to see a persistence of the [prairie farmer’s] log-cabin tradition in the overwhelming American preference for the detached house on a large plot. The customs and attitudes of the frontier still flourish. (Delafons 1969, 1, 4)

Of all the modern industrialized nations, the United States is the only one that began with what originally seemed to be an endless supply of land.… One of the important foundations of this country was that everyone was free to do what he wanted, partly because of the abundance of land. And that freedom certainly included control of ...