![]()

PART I

Introduction

![]()

CHAPTER 1

French Court Dance in Bach’s World

Germany was still recovering from the severe economic and social disruptions of the Thirty Years War when Bach was born in 1685. The Treaty of Westphalia had officially ended the bloodshed in 1648 by stipulating that the princes of each of the over 300 states and other political units would decide the religion and laws to govern their own areas of control, with free cities, such as Hamburg and Leipzig, excepted. The long period of reconstruction from the civil war was to last over a century, embracing all of Bach’s life. Many German courts and cities imported culture from France and Italy as part of a peacetime cultural competition, striving to build brilliant, elegant centers of civility which would outshine those of their neighbors. The standard biographies of Bach contain little about French influence, yet French culture was a forceful presence in most of the places in which he lived and worked.

For example, Bach would have encountered French language, music, dance, and theater while he was a student at the Michaelisschule in Lüneburg in 1700–1702. Though at school he studied traditional subjects, such as orthodox Lutheranism, history, and rhetoric, he shared room and board with the aristocratic young men who attended the Ritterakademie in Lüneburg. Karl Geiringer writes:

The Academy was a center of French culture. French conversation, indispensable at that time to any high-born German, was obligatory between the students; and Sebastian with his quick mind may have become familiar with a language which he had no chance to study in his own schools. There were French plays he could attend and, what was more important, French music he could hear, as a pupil of Lully, Thomas de la Selle, taught dancing at the Academy to French tunes. Most likely it was de la Selle, noticing the youth’s enthusiastic response, who decided to take Bach to the city of Celle, where he served as court musician.1

Bach visited the court at Celle many times; it was a “miniature Versailles” in its recreation of French culture, according to Geiringer. As an impressionable teenager, Bach probably encountered Lully’s music as played by the excellent French orchestra; the keyboard music of composers such as François Couperin, Nicholas de Grigny, and Charles Dieupart; and possibly ballet and French social dancing as well.2

Most of Bach’s titled dance music implies a connection to French Court dancing. Minuets, gavottes, passepieds, courantes, sarabandes, gigues, and loures were frequently performed at the courts and in the cities where Bach lived.

FRANCE

French Court dancing, a symbol of French culture, was especially in favor in Germany. This graceful, balanced, refined, and highly disciplined style was “invented,” as it were, or given its classic characteristics, by dancers working at the court of Louis XIV from the 1650s on.3 The technical achievements of this style—for example, turnout of the legs from the hips and the five positions for the feet (Fig. I-1), and the calculated opposition of arms to step-units (Fig. I-2)—were an obvious, stunning improvement over any other dance form in Europe. French Court dancing was not a fad, but the beginning of ballet. It was internationally accepted even as it was being invented and codified in France, not only in Germany but in England, Scotland, Spain, Portugal, Czechoslovakia, Holland, and Sweden, later spreading to Russia and the European colonies in North and South America.

Under the strong, central rule of Louis XIV (reigned 1661–1715), France experienced an especially prosperous and influential period of her history, unlike Germany with its many small, competing states. Louis XIV was a lifelong lover of aristocratic dancing. Even as a youth he and his friends dressed up in fanciful costumes and danced in ballets for their own entertainment. A ballet required the support services of scene designers, costumers, singers, dancers, poets, and musicians. Every year at least one new ballet was presented, most often in the season between Christmas and Lent. It was usual for a ballet to be organized around a theme, such as the seven liberal arts, or an event from classical mythology, such as the birth of Venus. Ballets normally did not have a strong central plot, but consisted of a series of vocal airs loosely organized around the theme. Sung by various characters, these airs were interspersed with dances (entrées) performed by various characters dressed in fanciful costumes.4

Aristocrats at the court of Louis XIV also enjoyed social dancing, using the same steps and movement styles as ballet but wearing formal dress instead of costumes. Elegant ceremonial balls were held to celebrate important events of the realm, such as a military victory, the signing of a treaty, the marriage of a socially prominent person, or someone’s birthday. They often occurred after an evening of theater or other recreation. But unlike social dancing today, these events were carefully planned and rehearsed, and only the best recreational dancers performed, while the assembled company watched and admired.

The king sat at the head of the room, with members of the court arranged around him according to rank. He and his partner danced the first dance, after which everyone else in the royal company danced, one couple at a time, again in order of rank. The dancing couple began at the foot of the room facing the king; the musicians were usually behind them or in raised galleries on the side of the room. Every dance began and ended with a formal Reverence to one’s partner as well as to the king. Almost all of the dances—minuets, courantes, gavottes, and other forms—consisted of special written choreographies which were memorized beforehand; other members of the court had learned the same choreographies and would know if they were performed correctly. Courtiers practiced daily in order to present a graceful picture while they danced. Other spectators might watch the ball from bleachers behind the central area but would not participate in the dancing.

In addition to these “grand balls” there were innumerable occasions for dancing, at court and at the private estates of noblemen. There were masked balls, with gaily costumed participants, at which a masquerade would be presented—a scene from a ballet, or a scene with dancing and singing invented for the party. The jours d’appartement took place on special evenings at the king’s palace, with dancing and other entertainments, such as gambling and billiards.

During the six-month period between 10 September 1684 and 3 March 1685, the beginning of Lent, there were at the court alone: 1 grand bal; 9 masked balls; 16 appartements that definitely included dancing; 42 other appartements that almost certainly also offered dancing; and at least 2 evenings of comedy that included dancing between the acts by courtiers.5

It was the French dancing masters who created the ballets, ceremonial balls, and masquerades. For ballets they choreographed the dances, rehearsed the ballet corps, coordinated the dancing with the music, and often performed in the productions. For the ceremonial balls, dancing masters were in charge of seeing that everyone observed the rituals, and at the proper time. The short theatrical presentations at masquerades also needed careful production. Dancing masters gave daily lessons to able aristocrats, including the king himself, to ensure that all the participants knew their parts and that the balls and ballets would be as magnificent as possible. In addition to teaching dancing they instructed courtiers in deportment, such as the proper way to bow to a superior or to an inferior, how to do honors in passing, what to do when introduced at court, what to do with one’s hat and sword, and so on. There were precise rules which, when followed, resulted in elegance and the appearance of gentility, the height of civilized behavior.

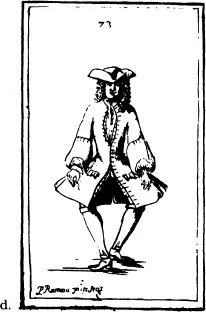

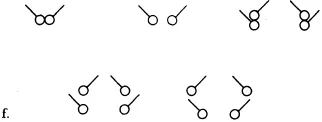

Fig. I-1: From Rameaur:Maître. a. Reverence before dancing (p. 62); b. First posture of demi-coupé (p. 71); c. Second posture of demi-coupé (p. 72); d. Third posture of demi-coupé (p. 73); e. Fourth posture of demi-coupé, balancing on one foot (p. 74); f. The five positions for the feet.

The technique of French Court dancing has been preserved, happily, through numerous dance manuals as well as a notation system which could record particular choreographies.6 The te...