![]()

PART I

Misogyny and Mayhem

![]()

1

Always Ambivalent

Why Media Is Never Just Entertainment

Abby L. Ferber

In this essay, I want to focus on the deep feeling of ambivalence I have about the Millennium trilogy. How can three books that I am so fond of be so upsetting? Feminist cultural critics often identify their feelings of ambivalence in analyzing popular culture (Douglas 2010; Henry 2007; Kennedy 2002). Diane Shoos (2010) highlights this in her examination of the “ongoing debates about the representation of, especially, the violated female body” and the central issue of visibility and invisibility in regards to violence against women (115). My own ambivalence revolves around these issues.

While reading the Millennium trilogy, I was reminded of the words quoted by Maria Guajardo at a conference for educators in 2009: “Our job is to comfort the distressed, and distress the comfortable.” These powerful words have stayed with me since I heard them: they capture what I aim to do in my teaching, and what I struggle with each semester. Can we do both at the same time? It is a balancing act I have not yet perfected. In teaching extremely difficult topics, including the history of slavery, lynching, rape, and sexual assault, I am constantly aware of the emotional impact of the subject matter on my students, as well as the toll it takes on me. We become, in effect, “secondary witnesses” to the horrors we examine (Jacobs 2010, 8). I pay particular attention to the texts and films I select with this in mind. While my intent is to reveal these hidden histories to my students, their own gender and racial identities affect their particular experience of the class. I know that intent and impact are not always consistent. No matter what Stieg Larsson intended, I believe the Millennium trilogy can potentially “distress the comfortable.” Yet at the same time, I am disturbed by its potential impact on those already distressed.

There are many reasons I love reading these novels. First, they are populated by strong, complex women. In her analysis of Lara Croft, Helen Kennedy (2002) observes that many feminist scholars have welcomed the increasing appearance of “active female heroines”; Lisbeth Salander certainly falls within this category. Like Croft, she is a “fantasy female figure” who resonates with the recent media construct of “girlpower.” Regarding the mystery-thriller genre, which is largely a bastion of men heroes and protagonists, Kennedy observes that “the general absence of such characters is part of the reasons why fans become so invested in these characters. . . . [The woman hero’s] occupation of a traditionally masculine world, her rejection of particular patriarchal values and the norms of femininity . . . are all in direct contradiction of the typical location of femininity within the private or domestic space.”

Larsson depicts women as equally capable as men, whether as news reporters, editors, police officers, lawyers, novelists, or board members. He also pays his dues to women writers. Whenever he mentions other authors in the trilogy, they are almost always women (including, for example, Sue Grafton, Val McDermid, Sara Paretsky, Elizabeth George, Astrid Lindgren, Dorothy L. Sayers, Agatha Christie, and Enid Blyton).

The Millennium trilogy also depicts the reality of women’s lives and the positive impact of the women’s movement and feminism. Throughout the trilogy, feminism is often referred to in a positive light, which is unfortunately rare in pop culture. Larsson credits the women’s movement’s many successes in creating women’s shelters, rape crisis centers, hotlines, and other resources. In Dragon Tattoo, he refers to women who experience domestic violence and are forced to seek “help from the women’s crisis centre” (41). At another point, he writes, “Gottfried Vanger . . . was the father of four daughters, but in those days women didn’t really count. . . . It wasn’t until women won the right to vote, well into the twentieth century, that they were even allowed to attend the shareholders’ meetings” (170).

As numerous scholars have detailed, the mainstream media has generally embraced a postfeminist perspective, one that assumes gender equality has now been achieved and oppression of women is largely a thing of the past (Douglas 2010; McRobbie 2004). As Angela McRobbie observes, “There is little trace of the battles fought, of the power struggles embarked upon, or of the enduring inequities which still mark out the relations between men and women” (260). Part of the appeal of Larsson’s novels is his direct and repeated refutation of these postfeminist assertions. For example, the statistics at the beginning of each part of Dragon Tattoo reveal the extent of violence faced by women in Sweden.

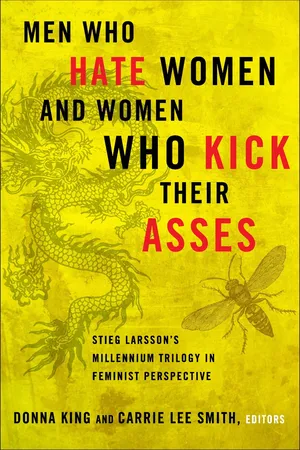

Larsson tackles this violence as an urgent social problem threatening women’s lives and well-being. The original Swedish title, Män som hatar kvinnor (Men who hate women), specifically names the widespread violence as men’s actions against women. This is crucial. In their book Gender Violence, Laura O’Toole, Jessica Schiffman, and Margie Kiter Edwards provide ample evidence that incidents ranging from sexual harassment to sexual slavery

have a common link: male perpetrators, acting alone or in groups, for whom violence and violation are rational solutions to perceived problems ranging from the need to inflate one’s sexual self-esteem to denigrating rivals in war to boosting a country’s GNP. They also demonstrate the real harm that women face on a daily basis in a world that views them sometimes as property, often as pawns, and usually as secondary citizens in need of control by men. (2007, xi)

Too often, we find books and articles that generically decry “violence against women.” Larsson’s naming of it holds men accountable (Shoos 2010). While violence in lesbian and gay couples is a real problem, and women do perpetrate violence as well, men nevertheless commit the vast majority of violent acts against women and men (O’Toole, Schiffman, and Edwards 2007).

Making this violence visible is the trilogy’s strength, but also the source of my ambivalence. I first begin to feel uncomfortable on page 195 of Dragon Tattoo, when an investigator tells Mikael Blomkvist, “What I’m talking about are those cases that stay with you and get under your skin. . . . This girl was killed in the most brutal way,” and then proceeds to describe it. These words produce a powerful affect. As I reread the passage, I feel sick to my stomach and the muscles in my jaw tighten. According to Melissa Gregg and Gregory Seigworth (2010, 1), this experience of “affect is found in those intensities” in the body. These unconsciously triggered “visceral forces” can either lead us to action or analysis, or leave us overwhelmed and immobilized. One minute I am reading this terrific book and enjoying it, and then all of a sudden, pow! It feels like a punch in the stomach, out of nowhere. From that point on, I am on guard; I can no longer simply enjoy the book. When I read this passage, I wonder if the detailed description of brutal violence is really necessary.

Experiences of sexual assault and exploitation loom large in the many descriptions of murdered women in Dragon Tattoo. Laura Mulvey argues that “the female body operates as an eroticized object of the male gaze” (qtd. in Kennedy 2002). This occurs in the two descriptions of Nils Bjurman sexually assaulting Lisbeth Salander (Dragon Tattoo, 222, 249). The second scene is especially graphic and violent. As the narrator observes after the attack, “What she had gone through was very different from the first rape in his office; it was no longer a matter of coercion and degradation. This was systematic brutality” (252). When I revisit these pages, I again wonder if these detailed descriptions are necessary or if they simply provide a “voyeuristic appeal” (Kennedy 2002); I feel increasingly ambivalent.

Larsson’s portrayal of men’s violence against women is nevertheless noteworthy because he does not reduce the issue to simply the actions of a few bad men. Instead, he presents it as a systemic, institutional system of inequality. According to the New York Times, “The overarching narrative is filled with the evil that men do to women—wives, daughters, prostitutes, even unlucky female passers-by. But the villains aren’t simply isolated rogues, as they tend to be in American movies; they’re also systems of oppression, ranging from the nominally personal (abusive parent and child) to the overtly political (oppressed citizen and state)” (Dargis 2010).

This reflects a feminist, sociological understanding of violence as not strictly an issue of physical force, but rather “the extreme application of social control. . . . It can take a psychological form when manifested through direct harassment or implied terroristic threats. Violence can also be structural, as when institutional forces such as governments or medical systems impinge on individuals’ rights to bodily integrity or contribute to the deprivation of basic human needs” (O’Toole, Schiffman, and Edwards 2007, xii).

Salander’s experiences of violence and trauma involving her father, the state-appointed psychiatrist, the security police, and her legal guardian exemplify this. Throughout the trilogy, men’s violence against women is conveyed as persistent and pervasive through numerous examples:

•Child prostitutes and trafficked women are exploited.

•Many women are murdered, especially those most vulnerable, including immigrants and prostitutes.

•Salander experiences street harassment.

•There are references to pornography depicting women experiencing violence.

•Both Erika Berger and Sonja Modig experience sexual harassment in the workplace.

•Richard Forbes attempts to murder his wife, Geraldine, at the start of book 2; there is a fleeting reference at the end of the book to “a middle-aged woman who had been killed by her boyfriend” (Played with Fire, 516).

•Richard Vanger is described as “a brutal domestic. He beat his wife and abused his son” (Dragon Tattoo, 89).

•Harriet Vanger was physically and sexually abused by her father and then her brother, both of whom turn out to be serial killers of women.

•We learn that Harriet’s cousin, Cecilia, was in an abusive marriage. After she divorced her husband, her father “began to berate her with humiliating invective and revolting remarks about her morals and sexual predilections. He snarled that no wonder such a whore could never keep a man. Then her adult brother responded with a ‘comment to the effect you know full well what women are like.’ . . . [Her] father made her childhood a nightmare and affected her entire adult life” (Dragon Tattoo, 256; emphasis in the original).

Larsson’s word choices are especially telling. He refers to Cecilia’s abusive marriage as “the usual story.” Elsewhere he writes, “Domestic violence . . . the term was so banal. For her it had taken the form of unceasing abuse. Blows to the head, violent shoving, moody threats and being knocked to the kitchen floor” (256). And earlier in Dragon Tattoo he writes, “Sometime in the forties a woman was assaulted in Hedestad, raped, and murdered. That’s not altogether uncommon” (195). By employing descriptors such as “usual,” “banal,” “not altogether uncommon,” Larsson emphasizes that violence against women is a fact of life for many.

Larsson takes us beyond the banal, however, in revealing that experiences of sexual abuse and domestic violence take myriad forms. We see here the range—the continuum—of violence against women, as well as the different ways in which women respond (Gavey 1999). For example, Cecilia’s case shows that verbal abuse alone can be devastating and lead to further victimization. These examples reflect a feminist conceptualization of rape as a point on a continuum with other forms of coercion that are far more common. As Edwin Schur puts it, “Intimidation, coercion, and violence are key features of sexual life in America today. We may profess to view coercive sexuality as deviant. But, actually, it is in many respects the norm” (1997, 80). This has prompted numerous feminist scholars to conclude that we live in a “rape culture” (Buchwald, Fletcher, and Roth 1993; Filipovic 2008; Wilson 2010).

In Larsson’s work, the reality of violence against women is in your face—impossible to ignore or gloss over. The strength of this approach is that it potentially distresses the comfortable. But what does it do to the distressed? My own discomfort continues throughout the trilogy. In Played with Fire, much of the story revolves around identifying the murderer or murderers of Dag Svensson and Mia Johansson. Blomkvist discovered their bloodied bodies. They are both described in equally gruesome detail, but it is Johansson’s image that is repeatedly invoked throughout the remainder of the text. Despite the fact that he had a closer relationship with Svensson, Blomkvist is haunted by his memory of Johansson’s remains on at least four separate occasions:

•The sight of Johansson’s shattered face could not be erased from his retina. (217)

•He still had the image of Johansson’s face swimming in his head. (221)

•Blomkvist rubbed his eyes. “I can’t get the image of Mia’s body out of my mind. Damn, I was just getting to know them.” (263)

•The image of Johansson’s face flickered before his eyes. (628)

There are no similar references to Svensson. It is the “repetitive trope” of the mutilated woman’s body that comes to represent the horror and tragedy of the murders (Jacobs 2010, 153). Lone Bertelsen and Andrew Murphie emphasize “the constitutive role of refrains—as found in the repetition of the image. . . . Refrains are affects ‘cycled back’ ” (2010, 139). Recall that affects—the intensities felt in the body, often difficult to name—can either mobilize or numb. The refrain of women’s violently murdered bodies found in the Millennium trilogy also exists within a culture where sexualized depictions of violence against women are endlessly repeated in a larger sociocultural refrain.

Affects are felt differently by differently positioned readers. These books trigger memories of many of my own experiences, which fall on various points along the continuum of coercion. Social psychological research on objectification theory, microaggression, and stereotype-threat all argue that “cues” experienced by subjugated group members that remind them of their marginal status can reinforce and contribute to the experience of oppression (Moradi and Huang 2008; Steele 2010; Sue 2010). According to Claude Steele (2010), these cues often take the form of identity threats. Identity threats can be very minimal, incidental, and even unconscious passing cues that reference one’s marginality. Yet research shows that they can powerfully influence one’s emotions, behavior, performance, and sense of self. Their affective impact is physiological as well, changing blood pressure, heart rate, and immune system functioning.

According to Steele, “The kind of contingency most likely to press [a social] identity on you is a threatening one, the threat of something bad happening to you because you have the identity. You don’t have to be sure it will happen. It’s enough that it could happen. It’s the possibility that requires vigilance and that makes the identity preoccupying” (2010, 74). The refrain of images of women experiencing sexual abuse can serve as an identity threat, reminding women that they are targeted for violence simply because they are women. In Jill Filipovic’s words, “The threat of rape holds women—all women—hostage. . . . The emphasis on rape as a pervasive and constant threat is crucial to maintaining female vulnerability and male power” (2008, 24).

Thus, we need to be aware of the potential harm such graphic depictions of violence carry. Janet Jacobs’s self-reflexive research on Holocaust remembrance resonates for me here. Despite the aim of using education to prevent genocide, there remain “problems inherent in representing the victimization of women . . . most notably the sexual exploitation of women’s suffering” (2010, 20–21). Larsson’s trilogy is littered with the bodies of mutilated, sexually assaulted, murdered women, which “invite fantasy and an objectification of the female victims” (Jacobs 2010, 43). In his work on “memory tourism,” James Young warns of the dehumanization th...