![]()

1

From Medicaid to TennCare: 1965–1993

THE EVENTS

IN 1935, PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT SIGNED the Social Security Act (SSA) into effect as part of the New Deal.1 As the name implies, the act is best known for Social Security, America’s earliest and best-known experiment with “social insurance,”2 but it also changed the structure of government assistance to persons in need in fundamental ways.

Prior to 1935, assistance for needy Americans was a local responsibility.3 Local and state governments provided most of the money; local officials distributed most of it through “general assistance” programs, which gave them wide discretion over who to help and how much to provide.4 Social Security created a political division between national universal entitlement programs where beneficiaries earned their coverage through years of payroll deductions and welfare-based systems where the recipients received benefits without having contributed. This division and its consequential class system have continued through today in the form of benefits as rights versus privileges.

In a dynamic that would be repeated many times in succeeding years, the availability of federal matching grants helped influence state and local policy choices. “Between 1940 and 1966 the number of individuals receiving cash payments under general assistance declined from four million to less than 600,000, while the number receiving categorical assistance rose from three million to over seven million persons.”5

In 1965, Congress again expanded federal responsibility for social welfare, this time for health care, and it created two very different systems: Medicare and Medicaid.6 Medicare, for Social Security beneficiaries, was based on the “social insurance” model: all American workers were placed in a single risk pool, paid “premiums” into a “fund” during their working years in the form of payroll taxes, and became entitled to receive benefits from the fund after age sixty-five.7 This design made Medicare an “entitlement,” and its sustainability did not depend on the annual budget process of collecting taxes and determining appropriations.8

By contrast, Medicaid was designed as a program of categorical assistance paid by a mix of state appropriations and federal matching funds operated under federal guidelines.9 Medicaid was created at the hest of southern states (whose agricultural workers did not qualify for Social Security, and thus would also be eliminated from Medicare eligibility) as a way to provide for their neediest citizens.10 At the time Medicaid was adopted, it was seen as a consolidation of the health care component of existing programs, such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), where cash assistance and medical care were being provided to the same populations from different funding sources.11 States were permitted to create their own programs, but the federal laws set the floor of provisions.12 What evolved was a complex combination of state and federal laws and funds mixing to serve states’ poorest, elderly, and disabled citizens.13 As each state contributed money to its Medicaid pool, the federal government would match that state’s contributions with a specific matching rate (with the federal government paying at least as much as the state paying) so long as the basic requirements were met.14 For example, in many states, for every $1 they spent, the federal government would give them $2 for the Medicaid program.15 Some states quickly modified their existing programs to shift costs for their neediest citizens to the federal government, while others created new ones to earn federal matching funds. Within five years, congressional leaders declared that a “crisis” of uncontrolled health care cost increases had developed.16

The roots of this “crisis” were more complicated, however, than states trying to get the federal government to pay for their programs. First, each state’s federal representatives had vested interests to provide as much as possible in the way of federally paid benefits for their constituents back home. The cost of coverage expansions were minimal to states (20 to 50 cents on the dollar), making them easy to support. Thus, the state and the federal representatives were both pushing for Medicaid expansion. In addition, some federal expansion programs were mandatory (or operationally so), which continued to add to Medicaid enrollees. Consider one example: in 1967, Congress created the Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program to provide medical care for poor children.17 The program developed in reaction to the “documented, widespread, and preventable mental and physical conditions among poor children, from preschool children to young draftees.”18 If a state had previously accepted Medicaid matching funds, it was required to include EPSDT services or risk losing all of the Medicaid funds on which it had come to rely.19 Adding medical coverage for children up to age twenty-one was politically popular; federal and state costs for the Medicaid program understandably grew once the program was adopted.20

The resulting pattern has been that Congress periodically expands the mandatory benefits and states periodically take advantage of the optional programs to expand the amount of federal money flowing to their states. Actual costs frequently exceeded projections at the state level, the federal level, or both, and political conflict ensued over who would be forced to pay for the “unexpected” costs or take political responsibility for shrinking benefits.21

In addition to the state-federal dynamic, the Medicaid system also fostered new advocacy coalitions between various interest groups. Suddenly, the physicians and hospitals (both providers) had a reason to join forces to lobby for more funding and more practice autonomy. When managed care companies were introduced in the 1990s, insurance companies banded together to keep provider payment rates down and increase profits. Patients wanted additional benefits with reduced costs, and, consequently, they opposed the restrictions proposed by both the providers and the insurance companies.22 Looking closer, though, even within a group like “the providers” (which might present a cohesive front on a larger or federal scale), factions such as not-for-profit versus for-profit or rural versus urban developed on a smaller or local scale. And, of course, all these individual groups interacted with the state and federal governments. Medicaid transformed a local, nonstandardized process for delivering charity care into a national program that increased the number of people receiving free services and provided significant incentives for individuals and groups to form coalitions to achieve specific policy outcomes.

Tennessee’s experience is illustrative of this coalition-forming process in order to solve major health care problems. Looking specifically at the state-federal dyad, when Congress adopted Medicaid in 1965, it limited eligibility to the required categories, “the aged, the blind, the disabled, and families with dependent children.”23 With the addition of some optional categories, such as “medically needy” (members with characteristics of one of the broad Medicaid categories, such as aged, disabled, or families with children but who do not meet the income requirements for assistance),24 Tennessee’s enrollment had reached 410,525 in 1988.25 In 1990, Congress required the states to cover all children in low-income families as a condition of receiving Medicaid funds,26 and Tennessee obliged; by 1993, Tennessee’s Medicaid enrollment was 758,574.27 Total Medicaid expenditures in Tennessee rose from less than $1 billion in FY 1987–1988 to over $2.8 billion in FY 1992–1993.28 Putting those numbers into a statewide economic context, in FY 1989–1990, Tennessee spent 41.7 percent of its total budget on health and social services, and its 4.8 million citizens averaged a per capita income of $15,900.29 By 1992, the state was spending 50.5 percent of its state budget on health and social services, the population had grown only by about 200,000, and the per capita income was $17,200.30

Tennessee, along with other states, developed strategies to maximize federal matching grants.31 One strategy was to take people whose medical expenses were already the state’s responsibilities (like foster children) and make them Medicaid-eligible.32 Another was to impose new taxes on health care providers, count the revenue toward the state’s Medicaid fund, which the federal fund program would match, and then return the money received as revenues back to the providers via elevated preferred provider reimbursements.33 Yet another strategy to maximize federal matching money was encouraging providers to “donate” to the state’s Medicaid fund.34 Again, because the state had the power to adjust the reimbursement rates for providers, it could then return the donated money to the hospital through elevated reimbursements rates after receiving expanded federal matching funds based on the “donation.”35 Thus, providers and state officials were operating as a cohesive coalition against the federal government to maximize health coverage for citizens and increase federal dollars without raising taxes on its residents.

Looking across the country, in the decades after Medicaid was created, combined tax collections of state governments grew rapidly, and states invested a part of that revenue growth in Medicaid.36 From the states’ perspective, they were responding to congressional incentives; but, from the perspective of fiscally conservative federal lawmakers, aggressive states were “achiev[ing] social welfare objectives by externalizing at least half the cost to federal taxpayers.”37

Facing voter resistance to expanding federal deficits, congressional members began calling for action “to restore the built-in fiscal and political-process constraints that had always been part of the cooperative federalism Medicaid philosophy.”38 Throughout the 1980s, state Medicaid program inflation had “outpaced” the medical inflation rate, which was already higher than the general rate of inflation.39 Consequently, in 1991, a Democratically controlled House and Senate passed the Medicaid Voluntary Contributions and Provider-Specific Tax Amendments (MVCPTA) to place a “tourniquet on the federal fiscal Medicaid hemorrhage.”40 Among other provisions, the act restricted federal matching funds for health care related taxes and donations from health care providers.41

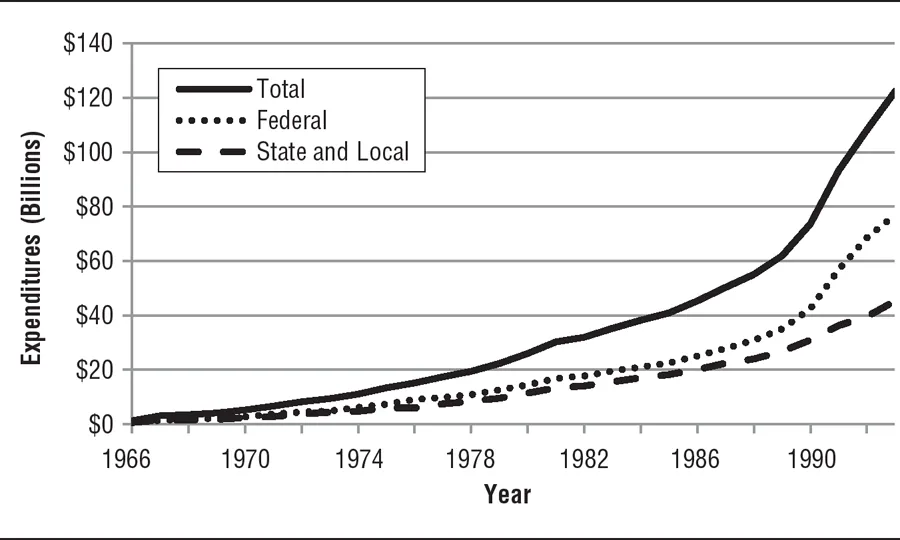

GRAPH 2: Total Medicaid Spending 1966–1993

Source: Data for Graph from CMS, National Health Expenditures 1960–2009. Available at www.cms.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/02_NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed Mar. 16, 2011.

Because the MVCPTA declared widely used strategies to be off-limit “loopholes,” the amendments created a fiscal and political crisis for the states. The act still permitted some payments, but state officials could no longer promise the providers they would receive all of their money back (“hold harmless”).42 This created a fear that wealthy hospitals would be forced to pay for the Medicaid...