- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Employment Relations in Non-Union Firms

About this book

The precise relationship between an employee and employer is often ambiguous within complex organizational boundaries. This book re-evaluates the way employment relations are conceptualized and examines employment conditions in non-union organizations.The authors present a detailed analysis of the conditions and patterns of employment relations in

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Employment Relations in Non-Union Firms by Tony Dundon,Derek Rollinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The non-union phenomenon

Introduction

This book deals with the nature of employment relations in non-union firms. In particular, it assesses the ways in which the employment relationship is made, modified and sustained in the absence of a trade union. The aim of this chapter is to set the scene for the remainder of the book. It starts by defining the term ‘non-union’ and this is followed by an examination of the increased significance of non-union firms in British employment relations. This matter is addressed in three stages: first, by considering the decline of trade unions; second, by examining recent trends in non-unionisation and finally, but more speculatively, by briefly examining future prospects.

Having established the current significance of the non-union firm, the next part of the chapter gives a brief review of the different approaches that have been used to study non-union employment relations. The aims of this investigation are then set-out, and the chapter closes with a brief synopsis of what is covered in subsequent chapters.

An opening definition

Since this book deals with employment relations within non-union organisations, it is fitting that it should open by defining what non-union means. It does not mean, as is sometimes implied, that there are no trade union members within these organisations. Rather, the expression is concerned with an absence of trade union recognition, and this has a legally defined meaning. A recognised trade union can be defined as:

a trade union recognised by management to any extent, for the purposes of collective bargaining.

Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act (TULR(C)A)

1992, S178(3)

Essentially collective bargaining is concerned with determining the conditions under which employees exchange their effort for rewards, which, if taken literally, could embrace any aspect of the pay–effort exchange. However, paragraph 3.3 of the recent Employment Relations Act (ERA) (1999) more restrictively defines it as concerning negotiations relating to pay, hours and holidays. In some situations non-union may not mean the complete absence of a trade union. Managers may choose to consult with a union in respect to certain sections of the workforce, while avoiding union recognition for other employees. To put matters simply therefore, non-union refers to an organisation in which management does not deal with a trade union that collectively represents the interests of employees, either for all or part of the workforce.

Of course not all non-union firms are the same. Some organisations may be non-unionised because management uses one or more strategies to avoid the incursion of trade union influence. In others it can occur more by accident than design, simply because trade union organisation has never been an issue. One attempt to map out the diversity of non-union types is provided by Guest and Hoque (1994), who suggest there are good, bad, ugly and lucky forms of non-unionism. The good non-union employer is derived from images of International Business Machines (IBM) and Marks and Spencer (M&S). It provides an attractive employment package and makes use of sophisticated Human Resource Management (HRM) practices, for example, devolved managerial systems, above average remuneration, training and development and recruitment strategies. The bad and ugly non-union firms are often dependent upon larger organisations for their work and operate in highly competitive markets. What can distinguish the bad from the ugly, is that in the latter, management seek to exploit workers, whereas in the bad, management offer poor wages and conditions without intended malice. If there is such a thing as a lucky non-union firm, then remuneration tends to be below the market average with few employee benefits. It is considered lucky because the issue of union recognition has probably never emerged with any significance.

However, there are problems with these conceptual non-union distinctions. One problem is that either/or categories of non-union firm tend to oversimplify and polarise practices that are, in fact, remarkably diverse and complex. It is also possible that so-called good non-union firms can be ugly at the same time; much depends on who you ask, what you ask them and when. As Edwards (1995) points out, while the absence of industrial discontent or union membership may indicate some level of commitment or trust between an employer and employee, it might also be a sign that there is a fear of management, because in the absence of independent facilities for employee voice, there are no remedies for discontent. Confusingly, some of the non-union literature is also replete with language that conveys an impression that unions are somehow less attractive to employees in so-called good companies. Here it is argued that because workers earn above average wages, then harmonious industrial relations are the norm, with little incentive to unionise. In part some of these problems are methodological. For instance, Guest and Hoque (1994) largely base their typology of non-union firms on the results of a survey of managers in these organisations, without asking employees whether they perceived their employers to be good, bad or ugly (Blyton and Turnbull 1998). Thus when non-union is used as a blanket term, it can disguise a wide degree of diversity between organisations and among organisational actors.

The increased significance of the non-union organisation

The decline of trade unions

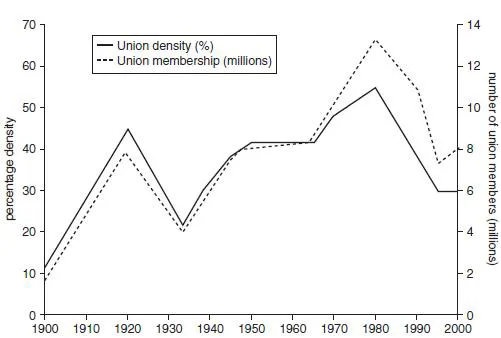

There have always been a large number of non-union organisations in Great Britain and for that matter, a correspondingly large number of employees who are not members of a trade union. In the last two decades however, the non-union firm has become much more commonplace and at the present time it could well be the most prevalent type encountered in Great Britain. This has not always been the case and to appreciate the current significance of the non-union organisation, it is necessary to examine historic patterns in British trade unionism. Figure 1.1 gives a simplified graphical representation of total union membership and union density (total membership as a percentage of those who could be members) as a time series across the twentieth century.

A number of observations can be made from Figure 1.1. First, trade unions have experienced varying fortunes since the turn of the century. Following a slow early period of growth, union membership fell sharply in the early 1930s, recovered after the Second World War, and reached a plateau throughout the 1960s. The peak year for union membership was 1979, thereafter falling back to levels comparable with those in the late 1930s. A second observation is that historically, periods of union decline have been followed by periods of growth, which more than compensated for the preceding losses. For example, higher levels of membership and density in the mid 1940s followed decline in the 1930s, and a similar, but much smaller trend is evident between the early 1960s and early 1970s. More significantly, although there has been a rise in trade union membership since the late 1990s, this has been very modest and nowhere near large enough to reverse the significant losses since 1979. In absolute terms this represents a loss of over 6 million members (from 13.5 million to 8 million), with a decline in density from 55 per cent to 32 per cent over the same period. Moreover, the decline has been virtually continual since 1979 and the level of unionism in Britain is now closer to its previous lowest point, which was encountered during the inter-war period (Cully and Woodland 1996).

Figure 1.1 Trade union density and total membership 1900–2000.

A factor related to this decline in membership is the extent to which collective bargaining has an impact on the terms and conditions of employees. This is important because collectively negotiated agreements about terms and conditions not only have an impact in unionised organisations, they also have knock-on effects in firms that do not recognise trade unions. In some of these firms, for example, management uses conditions established by collective bargaining elsewhere as a benchmark against which their own pay and conditions policies are established (Blyton and Turnbull 1998; McIlroy 1995). Between 1984 and 1998 however, the estimated proportion of employees in Britain for whom collective bargaining has the major influence in determining their pay and conditions fell from 70 per cent to 41 per cent (Millward et al. 2000). In short, not only are unionised employees a minority in Great Britain, but fewer workers have their terms and conditions influenced by the process of collective bargaining.

In broad terms there is considerable agreement that the decline in trade unions is attributable to four major groups of factors: structural/economic changes; political/legal influences; managerial attitudes and behaviour; and employee attitudes and behaviour. Reference to some of these arguments will appear in later chapters, where we discuss the nature of employment relationships and factors that can affect them. Suffice it to say here, that while there is agreement that all of these factors have been influential in some degree, the reader should be aware that there is far less agreement about the relative influence of any factor on its own. Explaining this decline in trade union influence is a fascinating issue in its own right. However, a detailed explanation is well beyond the scope of this book, the main purpose of which is to explain the nature of employment relations in the non-union firm. Nevertheless, to understand the increased significance of the non-union firm it is necessary to appreciate that along with the decline of trade unions, there have been other influences at work.

The changing contours of the non-union phenomenon

There has been a strong acceleration in the number of non-union firms, and data from the Workplace Industrial Relations Surveys (WIRS) show that the proportion of establishments with union members fell much more sharply after 1984. For instance, between 1980–84 the number of establishments reported in WIRS that had no union members remained constant at 27 per cent (Daniel and Millward 1984; Millward and Stevens 1986), suggesting that there were some gains to offset the decline in traditional unionised sectors. By the time of the third WIRS survey in 1990 however, the proportion of establishments with no union members had increased to 36 per cent, and by 1998 this figure had risen to 47 per cent (Cully et al. 1998). As a number of authors note, the net result was that losses during the mid 1980s effectively wiped-out the membership gains of the 1970s (Kessler and Bayliss 1992; Waddington 1992; Bird et al. 1993).

There is also important information about the concentration of non-union organisations, both geographically and by industrial sector.Table 1.1 shows that geographically, establishments that did not recognise a trade union were most prevalent in certain parts of the country, notably in London and the South of England. There is also evidence that new towns have emerged as non-union centres, especially where there have been positive attempts to attract inward foreign investment by Japanese and American firms (Oliver and Wilkinson 1992; Smith and Elger 1994). Similarly, certain industrial sectors seem to have a proportionately larger share of non-union firms, and examples include hotels, catering, retailing, hi-technology and professional service organisations. Younger establishments are also less likely to have a union presence than older firms (Beaumont and Cairns 1987; Beaumont and Harris 1988; McLoughlin and Gourlay 1994).

Table 1.1 Distribution of non-union organisations by geographical location and type of employee

Perhaps one of the more significant indicators of non-unionism is size of organisation. Table 1.2 shows that workplaces of under 100 employees have both a higher and longer tradition of non-recognition (Millward et al. 1992; Cully et al. 1998). It has also been reported that union membership (as opposed to union recognition) is at its lowest in smaller firms, with less than 1 per cent of those employed in small private sector establishments being members of a trade union (IRS 1998). Clearly, therefore, smaller establishments are of particular significance when considering non-union relations. Indeed, this would seem all the more important when the sheer volume of Small to Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) is taken into account (Dundon et al. 2001). In Britain, establishments with fewer than 50 employees account for 99 per cent of all companies, and organisations employing fewer than 500 workers provide 44 per cent of total employment (Storey 1994; DTI 2001).

Therefore, it seems likely that the sheer diversity of organisations could be an important key that helps unlock the mysteries of employment relations in the typical non-union firm.

Future prospects

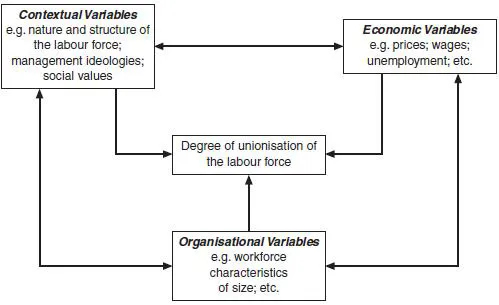

Given a strong current prevalence for the non-union firm, what then are the future prospects? Is trade union membership likely to increase in a dramatic way once again, or will it remain at its current modest levels for the foreseeable future? To try to give a definitive answer to this question is to risk setting oneself up as a latter-day oracle. However, a classic econometric study of historic patterns of growth and decline undertaken by Bain and Price in the 1980s provides some clues about the broad influences at work. Bain and Price (1983) identify three major groups of variables that are associated with trade union growth and these are shown in Figure 1.2.

The first group, Contextual Variables, consists of factors such as workforce structures, management ideologies and social values. Where there is a prevailing management ideology that considers trade unions to be an unwarranted intrusion, this will obviously result in opposition to them gaining entry into firms. Because manual workers in most industries have always shown a higher tendency to unionise, and white-collar workers have been somewhat less willing to join, workforce structures can also be an important variable. Finally social values are important in that the more that unions are accepted as a normal part of society, the more that joining becomes a naturally accepted act.

Table 1.2 Density of union membership in relation to workplace size

Figure 1.2 Influences on the level of trade union membership.

Source: adapted from Bain and Price (1983).

The second group of factors consists of Economic Variables. For example, as the real prices of goods rises, employees tend to unionise to protect their standards of living and when real wages rise, people tend to give the credit to trade unions, which reinforces the predisposition of people to join. Another economic factor is unemployment. If people are in work and perceive unemployment as a threat, they join trade unions for defensive reasons. However, if they work for an anti-union employer, and fear that their membership might be penalised, there can be a tendency in the reverse direction.

The final group of factors are Organisational Variables, such as increasing concentration of ownership into large organisations, the use of atypical or agency labour and the social-demographics of workforce populations. Unionisation is much more common in larger organisations, and with the possible exception of the public sector, unionisation is usually much lower in a workforce that is predominantly female, or has large numbers of atypical and peripheral employees.

From their analysis, Bain and Price draw the conclusion that since the Second World War, these variables have had different effects in different sectors of the economy, and this has a tremendous impact on the capability of trade unions to increase in size after a period of membership loss. In the public service and manufacturing, where, in the past, trade union growth has been the greatest, economic factors, favourable public attitudes to trade unions, and favourable employer policies all combined to give a major expansion. However, in sectors such as private services and the newer, high technology industries, although the first two factors were as positive as elsewhere, they were not strong enough to overcome the hostility of employers. Indeed, in the hotel and catering sector McCaulay and Wood (1992) found that the likely benefits for workers from union membership were often counter-balanced by fears of management reprisals. While this analysis largely explains matters in the past, its most important impli...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Routledge Research in Employment Relations

- llustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 The non-union phenomenon

- 2 The employment relationship re-visited

- 3 Factors affecting the employment relationship

- 4 Research methods and methodologies

- 5 Water Co.: A case of exploitative autocracy

- 6 Chem Co.: A case of benevolent autocracy

- 7 Merchant Co.: A case of manipulative regulation

- 8 Delivery Co.: A case of sophisticated human relations?

- 9 Towards an explanation of non-union employment relations

- Notes

- Bibliography