![]()

China’s Environmental Governance in Transition

ARTHUR P. J. MOL & NEIL T. CARTER

Introduction

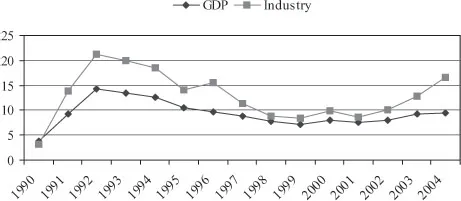

China has been witnessing an almost unprecedented period of continuous high economic growth during the last 15 years. The modernisation and transition process set in motion in the mid 1980s, started to accelerate and mature in the early 1990s, showing average national economic growth percentages of around 8 per cent and more (Figure 1). During the same time frame the Chinese economy opened to the global market, resulting in increasing international trade, growing Foreign Direct Investment inflows (and recently also outflows), and greater international travel by Chinese citizens. Economic development has been quite uneven, both sectorally and regionally. The eastern provinces and the industrial sectors have made the most contribution to the country’s economic acceleration, while economic development in the agrarian sectors of the west has been much less pronounced and in places is even stagnating. Modernisation patterns and technological innovations differ significantly between regions and between sectors. At the same time, not all groups in society have profited to the same extent from these developments. In general, a growing inequality can be witnessed in the country, where a new rich upper middle class has profited from economic development and access to the global economy, while significant parts of the Chinese population have suffered from rural marginalisation, the closing of inefficient state factories and reductions in the state bureaucracies.

Figure 1. Economic and industrial growth percentages in China, 1996–2004. Source: World Bank data.

As Shapiro’s (2001) impressive study illustrates, neither imperial nor Maoist China avoided environmental degradation, and the repression of human beings at least paralleled violence by humans towards nature. But rapid economic and industrial modernisation and development ushered in a new phase of continuous pressure on the environment. In this new phase there is no simple mono-causal and one-directional way in which economic development relates to the environment. On the one hand, economic growth, industrialisation (including some agricultural sectors), further urbanisation caused by a migrating rural population, increasing consumption levels, accelerated extraction of minerals and ores, and growing air and car transportation have resulted in increases in resource use and higher pollution levels. The increases (and predicted trends for the next decade) in car ownership, the penetration of durable consumer goods such as televisions, mobile phones, refrigerators and personal computers, and energy use are regularly reported in western journals and newspapers. On the other hand, technological and management innovations and developments, the entry into global markets, the increasing capacity of environmental state institutions, the commitments to international environmental treaties and the growing environmental awareness of China’s new middle class and ruling elites1 have contributed to increased efficiencies in resource use, the adoption of environmental technologies, cleaner products, lower emission intensities per unit of product, and the closing down of some inefficient (and thus heavily polluting) factories.

The overall impact of these contrasting tendencies differs, as can be expected in such an enormous country, between provinces and regions, between economic sectors, and among the social groups confronted with the positive and negative economic, environmental and social consequences of these developments. As in many countries, there is no one clear tendency in China. We can observe neither an overall tendency towards environmental decay jeopardising the global sustenance base, nor a general trend towards greening the economic, political and social institutions and practices. Understanding and interpreting current environmental developments in China in terms of a national environmental Kuznets curve, makes little sense. To evaluate the way that China is currently dealing with environmental problems and challenges, and the successes, failures and dilemmas it faces, we are in need of much more detailed analyses and insight into various institutional developments and social practices. These analyses are further complicated by the fact that China’s system of environmental governance is both very much in the making and under constant change and transition due to a fluid social environment, both nationally and internationally.

This introduction sets the stage for such dynamic analyses by first describing the historic development of what we might call China’s environmental state, including its successes and failures (some of which will be further elaborated in other contributions). The subsequent sections introduce the developments in those Chinese institutions that aim to contribute to diminishing the environmental burden produced by China’s unprecedented economic growth path.

The Birth of China’s ‘Environmental State’

In the birth period of environmental management (in the 1970s and early 1980s) China’s environmental protection system showed characteristics similar to those of other centrally planned economies, such as those in Europe before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. These included limited citizen involvement; no independent environmental movement or NGOs; little response to international agreements, organisations and institutions; a strong focus on central state authority and especially the Communist Party of China (CPC) with restricted freedom of manoeuvre for both decentralised state organisations, para-statals and private organisations; an obsession with large scale technological developments (in terms of hard technology); problems with coordination between state authorities and departments, together with a limited empowerment of the environmental authorities (see Ziegler, 1983; DeBardeleben, 1985; Lothspeich & Chen, 1997). The further development of China’s environmental reform strategy was not a linear process; there was no simple unfolding of the initial model of environmental governance invented thirty years ago under a command economy. Two main factors are behind a certain degree of discontinuity in Chinese environmental reform. First, the economic, political and social changes that China witnessed during the last two decades also affected the original ‘model’ of environmental governance. Economic transformations towards a market-oriented growth model, decentralisation dynamics, growing openness to and integration in the outside world, and bureaucratic reorganisation processes have shifted China’s environmental governance model away from those common to centrally planned economies. Second, China also witnessed the inefficiencies and ineffectiveness of its initial environmental governance approach, not unlike the ‘state failures’ (Jänicke, 1986) that European countries witnessed in the 1980s before they transformed their environmental protection approach.

The start of serious involvement by the Chinese government in environmental protection more or less coincides with the introduction of economic reforms in the late 1970s. Pollution control was initiated in the early 1970s, especially following the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. In 1974 a National Environmental Protection Office was established, with equivalents in the provinces, although its main development occurred after the enactment and implementation of the environmental laws and regulations since the late 1970s, with particularly rapid acceleration in the 1990s. Following the promulgation of the state Environmental Protection Law in 1979 (revised in 1989), China began systematically to establish her environmental regulatory system. In 1984 environmental protection was defined as a national basic policy and key principles for environmental protection in China were proposed, which include ‘prevention is the main, then control’, ‘polluter responsible for pollution control’ (already introduced in the 1979 environmental law), and ‘strengthening environmental management’. Subsequently, a national regulatory framework was formulated, composed of a series of environmental laws (on all the major environmental sectors, starting with marine protection and water in 1982 and 1984), executive regulations, standards and measures. At a national level China has now some 20 environmental laws adopted by the National People’s Congress, around 140 executive regulations issued by the State Council, and a series of sector regulations and environmental standards set by the State Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA).

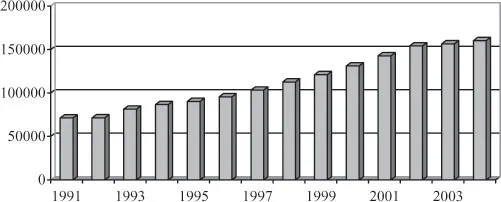

Institutionally, the national regulatory framework is vertically implemented through a four-tier management system, i.e., national, provincial, municipal and county levels. The latter three levels are governed directly by their corresponding authorities in terms of both finance and personnel management, while SEPA is only responsible for their substantial operation. The enactment of the various environmental laws, instruments and regulations through the last two decades was paralleled by a stepwise increase of the bureaucratic status and capacity of these environmental authorities (Jahiel, 1998). For instance, the NEPA, was elevated via the National Environmental Protection Bureau to the National Environmental Protection Agency (in 1988), and in 1998 it received ministerial status as SEPA. By 1995, the ‘environmental state’ had over 88,000 employees across China and by 2004 it had grown to over 160,000 (see Figure 2).2 Jahiel (1998: 776) concludes on this environmental bureaucracy: ‘Clearly, the past 15 years …has seen the assembly of an extensive institutional system nation-wide and the increase of its rank. With these gains has come a commensurate increase in EPB authority – particularly in the cities’. Although the expansion of the ‘environmental state’ sometimes met stagnation (e.g. the relegation of Environmental Protection Bureaux (EPBs) in many counties from second-tier to third-tier organs in 1993–94), over a period of 20 years the growth in quantity and quality of the officials is impressive (especially when compared with the shrinking of other state bureaucracies). Besides SEPA, the State Development Planning Commission (SDPC) and the State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC) are crucial national state agencies in environmental protection, especially since the recent governmental reorganisation in 1998.

Figure 2. Governmental staff employed for environmental protection in China. Source: China Environment Statistical Report (1991–2004).

In between State Successes and State Failures

Arguably, these administrative initiatives have contributed to some environmental improvements, although the widespread information distortion, the discontinuities in environmental statistics and the absence of longitudinal environmental data in China should made us cautious about drawing any final conclusions.3 Total suspended particulates and sulphur dioxide concentrations show an absolute decline in most major Chinese cities between the late 1980s and the late 1990s (Lo & Xing, 1999; Rock, 2002), which is, of course, remarkable given the high economic growth figures during that decade. By the end of 2000 CFC production decreased 33 per cent compared to mid 1990s levels, due to the closure of 30 companies (SEPA, 2001). It is reported (but also contested) that emissions of carbon dioxide have fallen between 1996 and 2000, despite continuing economic growth (Sinton & Fridley, 2001, 2003; Chandler et al., 2002). Most other environmental indicators show a delinking between environmental impacts and economic growth; for example, water pollution in terms of biological oxygen demand (World Bank, 1997). Many absolute environmental indicators (total levels of emissions; total energy use) show less clear signs of improvements (see Zhang & Chen, 2003, on air emissions; ASEAN, 2001; SEPA, 2005).

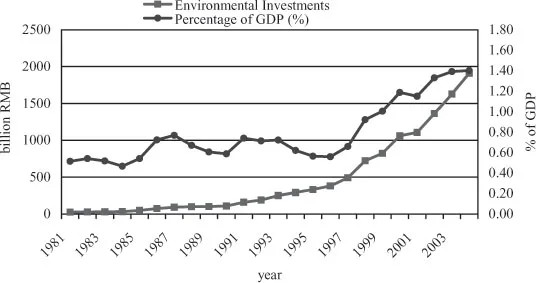

More indirect indicators that suggest similar relative improvements are the growth of China’s environmental industry, indicated by the proportion of sales to GDP: an increase from 0.22 percent in 1989 up to 0.87 percent in 2000. This is even more spectacular when taking into account the rapid economic growth over these years (average 9.4 per cent annually). Also the increase in governmental environmental investments is astonishing, rising from 0.6 per cent of GDP in 1989 to 1.0 per cent of GDP in 1999 and 1.4 per cent in 2004 (see Figure 3). The increase of firms certified with ISO14001 standards, from nine (in 1996), to around 500 (in 2000) to over 8800 (in 2004) (http://www.iso.ch/iso/), and the closing of heavily polluting factories following influential environmental campaigns during the second half of the 1990s (Nygard and Guo, 2001) point in a similar direction.

Obviously, these positive signs should not distract us from the fact that overall China remains heavily polluted, that emissions are often far above (and environmental quality levels far below) international standards, that only 25 per cent of the municipal wastewater is treated before discharge (although 85 per cent of industrial wastewater according to SEPA data; SEPA, 2001), and that environmental and resource efficiencies of production and consumption processes are overall still rather low. While relative improvements can certainly be identified, absolute levels of emissions, pollution, resource extraction and environmental quality often do not yet meet standards.

Environmental Governance: State and Market

How is contemporary China dealing with these current and prospective environmental threats and risks? What mechanisms, dynamics and innovations can we identify in China’s system of environmental governance? In setting the research agenda for such an analysis we have to bear in mind that we are trying to understand a moving target, quite unlike the more stable contemporary (environmental) institutions of European and other OECD countries. We will group our analyses of innovations and transitions in China’s environmental governance system in four major categories: political transitions, and the role of economic actors and market dynamics (this section), emerging institutions beyond state and market, and processes of international integration.

Figure 3. Governmental environmental investments, 1981–2004: absolute (in billion RMB) and as proportion of GDP. Source: China Statistical Yearbook (1981–2004).

Transitions in the ‘Environmental State’

The state apparatus in China remains of dominant importance in environmental protection and reform. Both the nature of the contemporary Chinese social order and the character of the environment as a public good will safeguard the crucial position of the state in environmental protection and reform for some time. Environmental interests are articulated in particular by the impressive rise of Environmental Protection Bureaux (EPBs) at various governmental levels. However, the most common complaints from Chinese and foreign environmental analysts focus precisely on this system of (local) EPBs. The local EPBs are heavily dependent on both the higher level environmental authorities and on local governments. However, as little importance is given to environmental criteria in assessing the performance of local governments, they often display no interest in stringent environmental reform, yet they play a key role in financing the local EPBs (see Lo & ...